The last words my daughter spoke to me were as sharp as a slammed door and just as final. “You’re useless now. Find somewhere else to die.”

I did what I had always done when life demanded obedience: I packed. The old suitcase I’d taken on our twenty-fifth anniversary trip to Charleston yawned open on the bed like a mouth too stunned to speak. I filled it with the careful order of a woman who’d kept a household running for forty-three years—nightgowns folded, wool sweater rolled, a single pair of pumps wrapped in tissue as if dignity could be preserved with paper. When I closed the zipper, a framed photograph rattled in the bedside drawer. Richard’s smile, boyish even at seventy-one, watched me gather the last proof of our life together.

By the time Jessica’s husband, Mark, carried my suitcases to the trunk of their new BMW, my hands had stopped shaking. I sat in the back seat and watched our house—the house I had painted and polished, repaired and replanted, the house that held the thud of my daughter’s childhood feet and the low laugh my husband could not suppress at any joke of mine—fall away in the rear window. The afternoon sun threw long bars of light across Oakwood Drive, turning the porch flag into a bright slash of red and white. I’d ironed that flag every Memorial Day. I’d climbed the step stool and clipped it to the staff myself when Richard’s knees couldn’t take ladders anymore. Jessica didn’t look back.

They left me at a motel called the Sunset Inn. Forty-nine dollars a night and you could hear the lives in the rooms on either side—televisions murmuring game shows, a cough, the muted squabble of strangers and love throttled into a whisper. Jessica pressed two hundred dollars into my hand as if I were a cab driver who’d gotten her safely through rain. “Just until we sort through Dad’s paperwork,” she said. Mark wouldn’t meet my eyes.

When their car pulled away, the motel’s sign buzzed and flickered, fighting darkness. I set my suitcase at the foot of the bed and sat. The mattress dipped, tired as an old friend. I placed the photograph of Richard on the wobbling nightstand and studied the calm of his expression. He looked like a man who trusted his own plans.

Richard James Peterson had been many things: stubborn, principled, a meticulous keeper of papers and keys; a man who would not leave the kitchen until every pan was hung precisely on its hook. Two years ago, he’d walked me through the will he’d written, the inventory of accounts, the passwords tucked into a tiny black notebook in his desk. He never treated me like a partner in the market—and Lord knows he could be condescending when arithmetic showed up to dinner—but he treated me like a partner in our life. He had never been cruel.

Guilt is a clever craftsman; it can carve doubt into any certainty. But even as the motel’s thin sheets scratched my shins and the air conditioner rumbled like a far-off train, one solid piece of belief remained: Richard would not have written a will that threw me out.

In the morning, I took the bus downtown. The ride ate three dollars of Jessica’s cash, and I counted the cost without flinching. The city dressed itself in glass and steel that reflected an April sky, and the attorney’s building rose with an old-world dignity, all polished brass and marble meant to quiet the spirit. I pressed the elevator button and saw my face in the mirrored door—a woman who had packed obedience and left the rest behind.

“Mrs. Peterson,” the receptionist said. “Mr. Vance will see you now.”

Arthur Vance had aged with grace and a gardener’s patience. His hair was white and neatly clipped; his suit was the kind of navy that made other blues feel impolite. I had expected him to blink at me with puzzled manners. Instead, he smiled as if I were a late guest at a dinner he’d set a place for anyway.

“Helen,” he said, coming around the desk. “I’ve been calling the house. Jessica told me you were traveling.”

“I am,” I said, and let the word sit between us until it ceased to be a euphemism and became simply true. “Arthur, I need to see my husband’s will.”

He frowned. “Of course. Jessica assured me you were present at the reading, but—well.” He opened a thick file. The paper had that heavy, expensive texture that tells the hand it is being asked to hold something important. Arthur offered me a chair and read. He read Richard’s name and the date, and the words unfolded like a path I’d already walked in my mind: the house on Oakwood Drive to his beloved wife, with all furnishings and personal effects; seventy percent of financial assets, approximately twenty-three million dollars; a trust of ten million for our daughter, Jessica, payable beginning on her forty-fifth birthday.

Arthur paused then, and looked over the top of his glasses as if the next lines carried more weight than the rest.

“Contingent,” he read, “upon her treatment of her mother following my death. In the event Jessica Peterson Hayes fails to extend to Helen Ann Peterson the dignity, respect, and care befitting a wife and widow, the trust reverts in full to my wife.”

I didn’t cry. Some mercies arrive too late to be spent on tears. I let the words stand on their own legs. They held.

“Arthur,” I said. “My daughter put me out on the curb like a chair with a broken leg. She told you I was traveling and had a reading without me. She handed me cash like a waitress.”

Arthur’s jaw worked as if he were chewing back something bitter. “We’ll need to freeze accounts immediately,” he said. “Notify the bank, the brokerage. I’ll contact Detective Miller at once. If Jessica presented forged documents to you—or to anyone else—we’re in criminal territory.”

He dialed and spoke with the efficiency of a man who’d memorized this choreography. While he was on the line with the bank’s fraud division, I studied the signature at the bottom of the will. Richard’s hand—confident but a little shakier in those last months—swept across the page as if insisting upon his own character. “Sound mind and body,” the words read. He would have smiled at that; he’d been vain about his health until the day his heart betrayed him.

Detective Andrea Miller arrived within the hour. She was in her forties, trim, with a kindness she wore like armor that had seen service. She listened to the story without interrupting, then asked to see whatever Jessica had shown me. I had nothing but memory.

“It’s enough,” the detective said. “Between the will’s contingency clause and your daughter’s misrepresentations to Mr. Vance, we have probable cause. We’ll move on the accounts and seek a warrant.”

The bank moved faster than grief. By late afternoon, everything Jessica touched went to ice. The joint accounts she had “assumed” control over, the brokerage login she had guessed at and changed, even the utilities she’d smugly shifted to her name—they froze as if winter had come early to Oakwood Drive. At 3:47 p.m., my phone lit with Jessica’s name.

“Mom?” Her voice carried the high note of someone accustomed to being obeyed by money. “There’s a problem at the bank.”

“I’m in Mr. Vance’s office,” I said. “He read me your father’s will. The real one.”

Silence is a truth-teller. On the other end, I could hear nothing but stunned air.

“You’ve made a terrible mistake,” she tried. “You don’t understand how complicated—”

“I understand perfectly. You forged your father’s memory and handed me a motel key.”

“Mom, you’ve never been comfortable with finances. You needed my help.”

“You’re right,” I said. “I needed help. Your father arranged it. He left me enough money to hire a legion.”

She hung up. Or the line died. It doesn’t matter which; endings are endings even if they put a pretty spin on themselves.

That night, I slept at home. I turned the key in the front door I had polished a thousand times, and the brass flashed as if recognizing my hand. Jessica had moved fast—closets half-emptied and re-filled with a young woman’s wardrobe, Richard’s tidy study invaded by glossy design magazines folded open to dream kitchens with islands large enough to dock a boat. I packed her things into contractor bags. I set them on the porch like a row of bulky mistakes and, for the first time since the funeral, made the bed on the right side without reaching for a second pillow.

The next day brought a surprise in a Chanel suit. Mark’s mother appeared at the door at eleven sharp, the kind of woman who believed the world was stitched to her hem. Cynthia Hayes had a delicate nose and a hard set to the mouth; jewelry gathered at her wrist like small suns.

“Helen,” she said with the arrogance of people who confuse pleasant diction with decency, “we must discuss this rationally.”

We did not agree on the definition of rational. But I led her into the living room and offered coffee as if hospitality, like grace, were a muscle that could be kept in shape with practice.

“My son made unfortunate choices,” she began, “but public prosecutions help no one. We’re prepared to make you whole—financially—and put this matter to rest.”

“How much is wholeness worth this season?” I asked.

She smiled. “Two million dollars in exchange for dropping charges against Mark. You’ll retain your home, of course.”

“Two million dollars to excuse a plan that would have left me in a motel,” I said. “You’re underbidding the market, Mrs. Hayes.”

Her smile thinned. “You’re a senior. This stress isn’t healthy. And if you force us to court, our counsel will be forced to explore…inconvenient details about your late husband’s business.”

“Threats are poor table manners.”

“Facts,” she said, rising. “Mark’s team has already found irregularities. I’d hate to see Richard’s memory dragged through the papers.”

After she left a trace of perfume and contempt in the hall, I called Arthur. “They’re hinting at skeletons,” I said. “If there are any, I want to meet them in the light.”

“You’re sure?” he asked.

“I’ve been underestimated my entire life,” I said. “I’d like to know the size of the room I’m in.”

He sent me a private investigator with eyes like a hawk and the patience of a carpenter. Rachel Grant carried no nonsense and a camera that whispered when it worked. We sat in Richard’s study amid the neat order he had loved, and Rachel read numbers like music. Wires. Shell corporations with names that sounded like empty rooms. Consulting agreements with nobody home behind a P.O. Box.

After six hours, she closed her notebook. “Mrs. Peterson,” she said, “your husband moved money. A lot of it. On paper it looks like laundering.”

“My husband didn’t even launder his own socks,” I said. The joke fell heavy.

Rachel’s face held only kindness. “I know what love sees,” she said. “I also know what paper proves. If a prosecutor reads this ledger, they’ll circle everything.” She hesitated. “The ten million in Jessica’s trust appears to route through the dirtiest lines.”

I stared at the desk blotter Richard had protected with the fastidiousness he had once protected me. A hole opened in my understanding and the floor tilted toward it.

“Tell me my choices,” I said finally.

“You could go to the FBI yourself, before anyone makes you go,” Rachel said. “You’ll lose a lot. Maybe not the house. Maybe not all of it. But you’ll walk in upright.”

“And if I do nothing?”

“Jessica and Mark will not. They will use this to bargain. They’ll paint themselves as helpful citizens who unearthed wrongdoing. You’ll be a bystander in your own ruin.”

The phone rang then, as if a stage manager had called for the next cue. Jessica. “Mom, we need to meet. Tonight.”

“I know everything,” I said. “About Dad’s money.”

She exhaled. “Then you understand why we need to make a deal. Mark’s lawyers are speaking with the FBI. We keep the house and five million in clean assets. The rest goes. My charges disappear.”

“Your charges don’t vanish,” I said. “They go into a different ledger. One labeled ‘cost of doing business.’”

“Mom, be practical. The alternative is losing everything.”

I hung up and looked again at Richard’s photograph on the bookshelf. The corners of his eyes had crinkled in and the light had always found him handsome. For the first time, I wondered what he had refused to say.

The FBI conference room smelled faintly of coffee and ink. Special Agent Diana Ross—no relation to the singer, she said with a quick smile that made me like her—listened while I placed my life on the polished table. Arthur sat beside me, a legal bookend, and Rachel watched like a sentinel from the far chair.

“You understand,” Agent Ross said, “that by coming forward you could be implicating yourself in benefiting from proceeds of crime.”

“I understand,” I said. “But I would rather walk in than be dragged.”

She took notes with a pen that did not scratch. The lights were bright enough to make truth feel like a medical procedure.

“Would you be willing to record a conversation with your daughter and son-in-law?” she asked at last.

“Yes,” I said, and surprised myself with the steadiness of my voice. Anger is a spine you don’t know you’ve grown until it holds your back straight.

That night at eight o’clock, I opened my front door to Jessica and Mark and a leather briefcase that looked heavy with contingencies. Jessica leaned in to kiss me as if nothing had cracked. “You look better,” she said, approval polished to a shine.

“Clarity agrees with me,” I said, and sat. Mark laid papers on the coffee table—the house to me, five million in assets certified clean, immunity implications dressed up as courtesies.

“Tell me something,” I said, after he finished his patient patter. “When did you first know about Richard’s money movement? Before you married my daughter or after you forged my future?”

Mark’s smile faltered, then regrouped. “Helen, your husband’s affairs are complex.”

“Agent Ross thinks so too,” I said.

The briefcase shut with a snap. Jessica’s knuckles whitened on her neat skirt. Mark stood, but Agent Ross and two other agents were already moving out of my dining room. It is a strange relief, watching handcuffs fasten on the wrists that once helped your daughter zip a dress.

“Jessica Sullivan-Hayes and Mark Hayes,” Agent Ross said, voice pitched for recorders and rights, “you are under arrest for conspiracy to commit wire fraud, elder abuse, and the attempted extortion of a federal witness.”

Jessica turned to me then, a child in the face where the woman had stood. “Mom,” she said, the single syllable breaking like glass. “How could you?”

“The same way you did,” I said gently. “With a plan.”

After the door closed on their outrage and fear, Agent Ross sat again. Her expression softened, the professional distance no longer needed.

“There’s something you should know,” she said. “About Richard.”

I braced for the fall. “Tell me.”

“He was working with us,” she said. “Deep cover. For years. The flows that look like laundering were part of an operation we authorized. He retained a percentage to protect his cover; we seized the rest when it could do most damage.”

The room swam and then steadied. The photograph on the shelf found a new angle to his smile, the one he’d worn when he planned something I couldn’t see yet. I felt anger burn through my ribs—not at the Bureau but at Richard first, for the secrecy; and then, slowly, a different heat that felt like grief rewritten as respect.

“Why didn’t he tell me?” I asked, knowing the answer even before she said it.

“He couldn’t,” Agent Ross said. “He protected you by keeping you separate. He died before we closed the loop.”

“How many?” I asked. “How much?”

“Forty-seven arrests,” she said, and her voice carried a quiet pride. “Over two hundred million seized. Your inheritance is clean. Legally. Morally, that’s between you and the life you build with it.”

I went to the window and looked at the porch, at the flag stirring in an April breeze. The light caught the edges of it and made it look like something a person might want to believe in again. “Then I will build,” I said.

Six months later, my kitchen smelled like coffee and lemon oil, and sunlight fell in generous rectangles across new countertops I had chosen for their quiet, practical beauty. The art studio that was once Richard’s study was bathed in morning, canvases stacked like promises against a wall. On the easel stood a nearly finished self-portrait: a woman with short silver hair and a mouth that had learned firmness without cruelty.

“Good morning, Helen,” said Dr. Sarah Grant—Rachel’s sister, my financial advisor, and a person who delighted in being both direct and kind. She slid a folder—a sensibly fat one—onto the breakfast table. “Your foundation’s first scholarships are funded. The pro bono legal clinic calendar is already booked through fall. And the Netflix deal is official.”

I laughed, because life is sometimes a comedian who knows timing. “The Mother’s Revenge,” I said. “Didn’t they pick a theatrical title.”

“You’ll have final cut,” Sarah said. “And the proceeds will go to the foundation. You’re leveraging attention into protection. I approve.”

I poured her coffee. “Any word from Jessica’s attorney?”

“He sent another letter,” she said carefully. “She wants forgiveness.”

Forgiveness is not a check you write because someone asks. “Tell him I hope Jessica finds the kind of repentance that changes the shape of a life,” I said. “Tell him that, for now, my role is to protect the life I’ve built from the damage of hers.”

Sarah nodded. She was a woman who knew that boundaries were a kind of mercy—the kind offered to all parties, even when it pinched.

After she left, the house settled into its afternoon hush, the kind of quiet that has muscle. I walked to the studio and uncovered the painting. The eyes I had painted watched me with the patience I had grown. I touched a small brush to the corner of the mouth, brightening a highlight until it looked like a woman had learned to smile again, but on her own terms.

When I stepped outside, the air felt like a permission slip. The maples along Oakwood Drive were throwing new leaves. Across the street, Mr. and Mrs. Alvarez were unloading groceries; their little boy waved with both hands and I waved back, overhead, big, as if unity could be made with gestures. The flag moved. The house stood. The woman who owned both took a breath and tasted coffee and paint and a relief so clean it felt like a new language.

The calls came, of course—reporters, advocates, women from church who said in whispers that their sons had borrowed their names on credit cards “just for a month.” I said yes to what would help and no to what would simply entertain. I learned to speak into microphones in ways that widened the small, stubborn circle of protection around women like me. I learned the math of my own money and then the joy of giving it away in directions that mattered.

When the documentary crew finally arrived, they padded through my rooms with socks and reverence, filming dust motes like stars. The director asked me to walk through my days. “Let the camera find you,” she said, and I smiled because I had already found myself.

Sometimes, in the soft dark of evening, when the cicadas in the yard hum like old machines and the porch light throws a sensible cone of yellow on the steps, I remember the motel room. The stained carpet, the buzzing sign, the way the air conditioner tried so hard to keep up. I think of how close a life can come to folding itself so small a person disappears inside it. I think of the sentence that tried to kill me: You’re useless now. Find somewhere else to die.

I answer it aloud, without drama, the way a woman says what is true when nobody can take it from her: I did not. I found somewhere to live.

On a Tuesday in early October, I painted until the light went gray. I closed the studio and walked into a kitchen that now held my taste and the murmur of an oldies station low enough to be companionable. I set two mugs by the kettle—one for me, one for whoever might stop by—and noticed the red dot on the answering machine. Rachel’s voice: “We’ve closed out the last of the case paperwork. Agent Ross sends her best. She says you should consider speaking in D.C. this winter. They’re listening.”

It still astonishes me: that people who never knew my name want to hear me say the words that once felt too small to matter. It makes me laugh sometimes, there at the counter with the steam rising and the house holding its steady shape, that what saved me in the end wasn’t a miracle. It was paperwork and persistence. It was showing up where the truth was kept and insisting it be read out loud. It was trusting that love—my husband’s, hidden and imperfect, and mine, stubborn and finally self-directed—could outlast the schemes of people who believed I would always fold.

A week later, the foundation’s first scholarship students came for dinner. Two young women and a young man—one studying law, one social work, one accounting—sat at my table and ate pot roast as if it were the first good meal in a season. They listened while I told the efficient version of what had happened to me, and they asked the questions that people ask when they’re brave enough to become necessary: How do you design a system that’s hard to trick? What are the early warning signs in a family where love has been replaced by leverage? What does it cost to forgive wisely and what does it cost to refuse?

After dessert, the young man looked at the self-portrait on the studio wall and said, “I like that she’s looking away.”

“She’s looking toward,” I corrected, and he smiled as if the verb itself had opened a door.

When the house was quiet and the dishwasher stitched its tidy seam through the racks, I took out the tiny black notebook Richard had kept. I’d moved it to my nightstand, not because I needed it, but because it was a relic of the bridge he built in secret to bring me to safe ground. I do not excuse his secrecy. I do not sanctify it. But I understand it in a way I did not before the world split around my feet. We loved each other in the ways we were each able. In the end, that love held.

Jessica will be eligible for early release at the end of the year. Her letters arrive twice a month, careful cursive on lined paper. I stack them on a shelf in the guest room, next to the afghans my mother crocheted in the eighties and a box of grade school art projects labeled “Jessica—third grade.” When I am ready, I will read them. If she has changed, I will recognize it. If she has practiced contrition like a language she finally intends to speak, I will hear it. But I will not mistake sentiment for safety, or wishful thinking for wisdom. I have earned the right to require evidence.

I visit the cemetery on Sundays. Richard’s grave is beneath an oak that drops acorns like teaberries, and I carry a small whisk broom in my tote to clear the stone. I tell him what I’ve spent and what I’ve saved, what I’ve given away and what I have planned. I tell him about the students, about the documentary, about the day the governor’s office called to ask if I would consult on a task force and how I laughed until the woman on the phone laughed too.

“Look what you started,” I say to the air, and the leaves answer. Or the wind does. Or nothing does, and silence is its own reply.

In November, frost etches the yard, and the maples let go of the last of their pride. On a cold morning, I open the studio blinds and stand in the light’s sharp square with my arms folded. The woman on the canvas meets my eyes. She is not the kind of pretty that sits quietly in a picture frame; she is the kind of beautiful that does not apologize for occupying space. I lay a tiny amount of paint on a palette knife and make a single, decisive stroke in the corner of the background where the shadows gather. The painting takes the stroke and becomes more itself.

So do I.

There’s a story people like to tell about reinvention, as if a person erupts from a chrysalis wearing the life they always wanted like a new coat. I prefer the slower stories—the ones where a woman learns the passwords to her own accounts, shows up at a bank with a folder of documents and a face that will not bend, sits in a room with other women and says, “Here is how you make a copy. Here is who you call. Here is what they cannot take.”

The night the first snow comes, I am alone in the house and not lonely. The radiators click like polite applause. I make cocoa, real cocoa in a saucepan the way my mother taught me, and carry it to the front window where the flag on the porch is stilled by white. Across the street, a string of Christmas lights goes on all at once and the Alvarez boy whooped into the cold. I lift my mug to him from behind the glass and he sees me and waves again with both hands. I wave back, extravagant as a queen.

If you pressed your ear to the glass, you might hear the quietest sound in the world: a woman’s life, settling into the shape that fits her.

On New Year’s Day, I drive to the ocean. The road unwinds like ribbon and the sky is the kind of bare blue that makes a person believe in beginnings. I park, walk to the water, and let the wind take the tears that come without permission and without shame. My phone buzzes with a text from Agent Ross: Happy New Year, Helen. The Torino trials begin Monday. You won’t have to testify. I write back: Happy New Year. Thank you for believing me. Thank you for teaching me to believe myself.

A gull drops a shell on the sand. It shatters and the gull eats what it needs. I laugh aloud, because the world is always teaching, isn’t it? You crack what you must. You take the nourishment you can. You leave the sharp edges for the tide to soften.

I stand there until my cheeks numb and my heart warms. Then I turn and walk back up the beach and into the year ahead, my boots marking a path that is only mine to make.

News

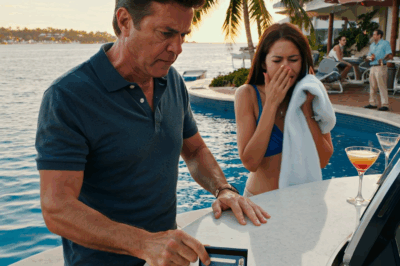

While the entire ballroom was applauding, I saw my mother-in-law quietly drop a “white pill” into my champagne flute — she thought I’d drink it; I swapped the glasses and smiled; she raised hers, the music jolted to a stop, every eye snapped our way — and that was the moment the wedding turned into an unmasking no one saw coming.

At My Wedding Reception, My Mother‑in‑Law Slipped Something in My Champagne—So I Switched Glasses I saw her hand hover over…

“My Dad Works at the Pentagon,” a 10-Year-Old Said. The Class Laughed, the Teacher Smirked—Ten Minutes Later, the Door Opened and the Room Went Silent.

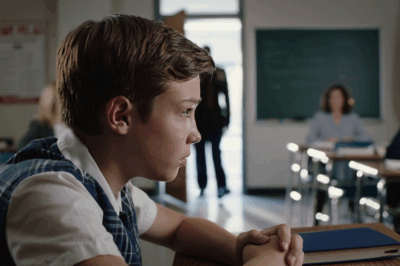

When the bell for morning announcements chimed through the beige halls of Jefferson Elementary, Malik Johnson straightened in his seat…

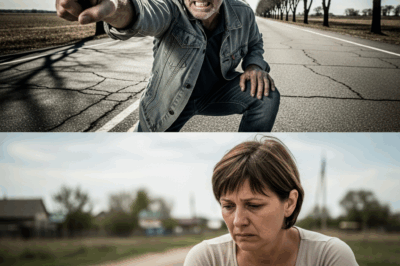

My dad dragged me across the driveway by my hair for blocking my sister’s car…

My dad dragged me across the driveway by my hair for blocking my sister’s car. The gravel scraped beneath my…

END OF IT ALL – I was told over and over again that I was not welcome at any family events. My mother yelled that events were for real family only.. So when I got married I didn’t invite them and they went crazy asking to fix things but I called such a call

I was taught early that belonging had rules nobody bothered to write down. You learned them by touch: a hand…

On My 29th Birthday My Parents Ignored Me And Sent My Sister To Hawaii — “She’s The One Who Makes Us Proud.”

The morning I turned twenty-nine, my apartment sounded like a paused song. No kettle hiss, no buzzing phone, no chorus…

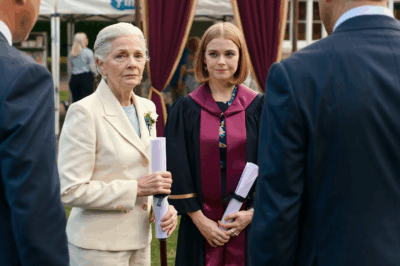

My wealthy grandmother said, “So, how have you spent the three million dollars?” — I froze right there at graduation — and my parents’ answer silenced the entire family…

The graduation ceremony stretched across the manicured lawn like a postcard of American triumph—burgundy and gold banners, folding chairs squared…

End of content

No more pages to load