The morning I realized my wedding necklace was gone, the house on North Capitol Hill felt colder than any February rain. The drawers in the cherry dresser stuck the way old wood does in damp weather; my thumbs left half-moon prints on the velvet-lined trays as I rifled through them. Empty spaces gaped back at me where a life used to be: my grandmother’s slim gold bracelet shaped like a rope of light, the oval sapphire earrings James had fastened in my lobes the night we were married, the delicate chain he’d given me with a breathless grin and a vow to never let me feel alone. It wasn’t the metal I wanted. It was proof. It was the breadcrumb trail of women who had come before me and refused to be erased.

“Where’s my wedding necklace, James?” I asked from the bedroom doorway, the velvet boxes open in my hands like small coffins.

From the living room, he didn’t bother to look up. The blue glow of his phone lit his face. “I sold them.”

Silence fell so hard my ears rang. “You… what?”

He sighed like I’d asked the weather to change. “Be reasonable, Anna. My mom needed the money. She raised me, remember? She needs it more than you do.”

The words struck with the dull finality of a door locking from the other side. “You sold my jewelry. Without asking me.”

He stood and planted his hands on his hips—a planning posture, the same stance he used when arranging his fantasy football lineups, the one that made me feel like an item on a list. “You’re acting like it’s the end of the world. It’s just stuff. My mother’s medical bills are piling up. You know she’s been struggling since Dad passed.”

My mouth went dry. “I understand helping her, James. But you don’t sell my things without telling me. That necklace—” My throat burned. “—that necklace was my mother’s. It’s all I have left of her.”

He rubbed his temples. “I’ll buy it back when we have the money. Don’t make this about yourself. My mom is family.”

“I thought I was your family,” I whispered.

He flinched, then picked up his phone again, the conversation closed like a drawer.

I slept with the light on that night, the way I had as a child after thunderstorms rattled the pane over the twin bed. In the yellow wash, our wedding photograph seemed almost kind: the spray of blush peonies, my veil blowing off the Bainbridge ferry like a pennant, his hand over mine as if to map our future. If you stared long enough, you could pretend a photograph promised something. But a photograph can’t sign a contract. It can’t stop a pawn ticket from wrinkling in someone’s pocket on a rainy walk down First Avenue.

The next morning, I drove to the pawn shop he mentioned. It was tucked into a brick building in Pioneer Square with a flickering neon sign that promised cash for gold. The bell above the door dinged when I entered. The air smelled like metal and the soft, sweet dust that lives in old carpet. The owner was an older man with silver hair and eyes the color of the Puget Sound on a gray day. He listened with the quiet of someone who’d seen too many versions of the same story.

“Sorry, ma’am,” he said when I finished. “It was sold already—all of it. To a woman named Martha Lewis.”

Martha. His mother.

It’s a strange thing to watch your hands shake yet feel steady in your bones. I thanked the man, took the useless receipt he offered—a receipt that recorded nothing I cared about—and drove east toward a neighborhood of trimmed hedges and quiet driveways. Martha opened the door on the third knock, wearing a cardigan the color of old roses and my mother’s gold bracelet on her wrist. It looked wrong on her. Not because it was mine, but because she wore it like a victory.

“Oh, Anna,” she said, sweet as an overripe peach. “You shouldn’t be so materialistic. It’s just jewelry.”

But it wasn’t just jewelry. It was trust, and both of them had sold that too.

I left her house without raising my voice. Rage like that deserves an audience it will never get. In my car, I pressed my forehead to the steering wheel and breathed until my pulse stopped thudding in my ears. Then I drove home and made a list.

The days that followed tightened around me like a too-small sweater. James moved through the house in careful arcs that didn’t intersect mine. He became almost polite, which is to say, he decided to pretend. I made dinners he didn’t eat while they were warm. He washed dishes in silence while I checked email for my interior design clients—an old Craftsman in Queen Anne that needed to feel like it remembered its own history; a Ballard bungalow whose owner wanted “light and Scandinavian” and didn’t know that meant more than buying white slipcovers. We spoke like colleagues with an unpleasant shared task.

One night, as rain braided itself over the windows, I walked past our bedroom and heard his voice low and urgent. “Yes, Mom… I sent you another two thousand. Don’t worry, Anna won’t notice. She’s too busy at work.”

A strange calm slid over me, an ice-slick over hot sand. When he hung up, I asked without any decoration, “You’re sending her our savings now?”

He frowned as if I were a child who had tripped and then blamed the ground. “She needs it, Anna. You wouldn’t understand.”

“I understand perfectly,” I said, my voice steady. “You’ve been lying to me, stealing from me, and calling it love. Do you hear yourself?”

He slammed his hand on the table hard enough to make the silverware jump. “Watch your tone. My mother sacrificed everything for me. You can’t compare to her.”

“Then maybe you should have married her,” I said.

He left, the door slamming hard enough to rattle the frames on the wall. The house shuddered, then went very still.

I poured coffee and opened the laptop at the dining table, the one we’d found at a thrift store the year we moved in and refinished together on the patio, laughing at how the stain kept catching in the grooves. I clicked through to our accounts. The numbers were not theoretical; the transfers had dates and times, timestamps that told a story without adjectives. Over fifteen thousand dollars in six months. Our house fund reduced to the phrase “we’ll figure it out.” My hands trembled as the printer spat out each transaction. I slid them into a manila folder and wrote the date on the tab.

The next day, I sat in a chair that tried to be comfortable across from a lawyer named Carmen Rodriguez. Her office on Second Avenue looked over the ferries cutting their rituals across the water. A little succulent on the windowsill refused to die. I told her everything. How he’d sold the jewelry without asking; how his mother had worn my mother’s bracelet like a borrowed triumph; how the savings had seeped away while he told me to be reasonable.

“If he’s taking joint funds without your consent and for non-marital purposes, that can be considered marital waste or misappropriation,” she said, her voice a measured instrument. “Washington is a community property state. The court cares about patterns. Documentation helps.”

“I don’t want to blow up my life,” I said. “I just… I want the hemorrhaging to stop. I want respect to mean something.”

“It does,” she said. “But sometimes you have to name the wound before it will heal.”

I drove home with the folder seat-belted into the passenger seat like a small, expensive child. The sky had peeled back into one of those Seattle afternoons that tricks you into believing in light. I parked and sat for a long time, listening to the ticking engine. Then I walked inside and told James I wanted a separation.

He laughed without humor. “Over some jewelry and a few dollars? You’re unbelievable.”

“No,” I said. “Over respect. Something you sold along with my mother’s necklace.”

Packing is a study in what the body remembers. My hands knew which sweaters felt safe and which shoes had betrayed me with blisters at weddings where strangers had said, “So how did you two meet?” I wrapped framed photographs in newspaper and found myself reading old headlines to avoid looking at our faces. I left him the couch he loved and took the coffee table I’d restored. I left the Dutch oven and took the knives. The house and I disentangled ourselves like two people who had danced politely and then agreed never to try again.

My new apartment was a one-bedroom with squeaky floors near Pike/Pine. The windows looked over a narrow alley where a breakfast place set out crates of oranges every morning, the smell of citrus a kind of prayer you could breathe. On the second night, Mrs. Rodriguez called to check in. “Move quickly on changing any passwords,” she said. “Order your credit reports. Keep records of everything. And Anna?”

“Yes?”

“Breathe. You are not the first woman to walk this road, and you won’t be the last. But this road does lead somewhere.”

I made a list and put it on the refrigerator door under a magnet shaped like a ferry. I changed passwords, closed the joint credit card, and set up alerts I should have set months ago. I emailed clients from a new work address and told them I’d be taking on more projects. In the evenings, I walked through Cal Anderson Park with a thermos of tea and watched teenagers kick a soccer ball under the lights, their laughter traveling clean as bells.

James called. He texted. He left voicemails that began with apology and ended with admonishment. “Mom didn’t mean any harm,” he said over and over. “She’s family. Don’t be selfish.”

I stopped answering. Silence, it turns out, is a language that has to be learned.

Work caught me by the wrist and pulled me forward. I spent mornings on a Queen Anne porch examining the way the afternoon light would move through a set of leaded windows; afternoons with a contractor named Eli Walker who cursed like a poet but cut crown molding with a tenderness that made me want to hand him something fragile. I picked tile that would age beautifully, a green so soft it felt like continuing instead of starting over. I learned the names of sorrow I hadn’t allowed myself to say: betrayal, dismissal, erasure. I learned I could say them and still choose paint colors that made people weep in good ways.

One afternoon, an envelope arrived from the pawn shop. Inside lay my sapphire earrings on tissue paper like two small drops of ocean and a handwritten note. Mrs. Lewis sold these back, the owner had scrawled. She seemed regretful. Said they belonged to you.

I sat at my narrow kitchen table and cried in a way that made no sound. I touched the earrings; I didn’t put them in. I wasn’t sure what to do with a gesture that complicated. Martha had been cruel. She had also, apparently, remembered that she had not been given the right to rewrite my history. Both could be true at once.

Months pass differently when you’re rebuilding. The calendar pages don’t thud. They float. By May, the Queen Anne house smelled like sawdust and lemons—clean work and clean endings. Eli and I stood in the completed front room one Friday at six when the light was doing that thing that makes wood grain look like living veins. “You did good,” he said, squinting, which I’d learned was his version of affection.

“We did good,” I corrected.

He lifted a shoulder. “You gonna celebrate?”

“I thought I’d go home and eat cereal from a wine glass,” I said. “It’s been that kind of month.”

He laughed. “You deserve better cereal.”

When I reached my apartment, a man was waiting under the awning, rain slicking his hair to his head. It took me a beat to recognize him because I had practiced not seeing him. James looked thinner, the healthy gloss of entitlement stripped. He held his hands out in that old placating gesture. “Anna,” he said. “I know you don’t want to talk to me, but please…”

“What do you want?” I asked. My keys stayed in my hand.

He swallowed. “I made mistakes. Everything’s a mess. Mom’s house—there were liens I didn’t know about. I tried to fix it. I emptied my accounts. I thought I could keep her afloat and us too, but—” His voice cracked. “I need you.”

Once, I would have moved toward that break in his voice. Once, I would have wrapped both of us in a solution and called it marriage. Now I stood still. “You needed me when I was useful,” I said, not cruelly. “But you sold everything that made us a family—for her approval.”

“I’ll change,” he said. The words were small against the hum of traffic and the soft hiss of rain. “I’ll buy back everything. I’ll—”

“You told me to be reasonable,” I said. “I am. Reason tells me that trust, once broken, can’t be bought back.”

His shoulders dropped. He looked like a boy in a suit that doesn’t fit. He glanced past me into the glow of the lobby where Mrs. Finch’s potted ficus had decided to thrive against all odds. “I thought love meant never giving up,” he said.

“Sometimes it means letting go before you destroy each other,” I said. “Sometimes it means you turn around on a bridge and walk back to the side you came from.”

He nodded like someone who had finally located the map in his own hands and realized he’d been holding it upside down. “I’m sorry,” he said, and the apology, late and thin, still mattered because the truth usually does, even when it doesn’t change the outcome.

He walked away. The door breathed closed behind me.

Some endings are quiet. You sign papers in a room with humming fluorescent lights and a pen someone has chewed. You slide keys across a table. You separate your forks. You choose to stop telling the story in the old tense. You get new toothbrushes.

On a Sunday in June, I drove to a pier market and bought a small, battered workbench from a man who said it had belonged to his father, who had repaired watches in a town no one writes songs about. I carried it up the stairs to my apartment in two trips and set it near the window. I laid out the earrings and the empty chain box and a packet of seed beads I’d bought years ago because the color reminded me of my mother’s laugh. I wasn’t going to make jewelry; I was going to mend a timeline. I strung the beads into something that didn’t pretend to be important to anyone but me. When I finished, the sun had made its way to the lip of the building across the alley. The oranges glowed in their crates like small planets.

When grief loosens, it doesn’t announce itself. It doesn’t arrive with a marching band. It happens while you’re sanding a windowsill or choosing drawer pulls or learning your neighbor’s dog’s name. It happens when you unlock your front door and your body doesn’t brace. It happens on a ferry at dusk when the water is slate and the air is iron and you realize that a thing you thought would break you let light in through the seam.

In late summer, I toured a Craftsman in Phinney Ridge with a client who wanted “warmth without clutter,” which, like most things worth wanting, turned out to be a practice rather than a purchase. As I spoke, I watched her eyes soften, the way people’s faces change when they realize their home can be a place that treats them kindly. Afterward, she asked how I’d gotten into design. I told her the truth: that I loved the way rooms could tell stories that healed people. That I believed in the labor of light. That a house, like a life, can be rebuilt without needing to erase the bones.

On the way back to my car, I passed a small jewelry store I’d never noticed, the glass filled with handmade pieces that looked like memories you could wear. A woman with white hair and a sunburst ring on her thumb stood at the counter with a soldering torch. She looked up and smiled. “Want to see something?” she asked.

She brought out a pendant, a tiny circle of lapis set in gold. “I started this the day my oldest moved across the country,” she said, laughing softly. “I tell people it’s sky you can keep.”

I held it in my hand, feeling the weight—neither heavy nor light. “I used to have a sapphire necklace,” I said. “It was my mother’s.”

“I’m sorry,” she said, and then, without pity, “Do you have a story for this one?”

“I might,” I said. “I’m learning to write new ones.”

I didn’t buy it. Not then. I didn’t need a replacement, and I wasn’t interested in revenge disguised as shopping. But I went back three weeks later and commissioned a piece from her: a small gold circle stamped with a line I had drawn with my eyes closed. When it was finished, she handed it to me on a soft cloth. “What’s the line mean?” she asked.

“It’s a ferry wake,” I said. “From the day we were married. It’s also a fault line. It’s also a horizon.”

She nodded as if that made perfect sense.

Sometimes you get back what was stolen. Sometimes you don’t. Sometimes what returns is the part of you that handed your heart over like a permit and asked for permission to exist. I wore the gold circle on a plain chain that didn’t pretend to be important, and every time I clasped it, I thought of my mother in her kitchen, slicing peaches with a paring knife, the afternoon sun making an altar of her hands.

In October, Martha sent a card. The front had a watercolor pumpkin that made me think of craft fairs and church basements. Inside, in her careful script, she wrote: I’m sorry for my part in everything. I sold the bracelet. I used the money to pay a bill. It wasn’t mine to wear. I hope you’re well.

I held the card over the recycling bin and then tucked it into a drawer instead. Forgiveness, I was learning, doesn’t obligate reconciliation. It doesn’t require you to go back to someone who has shown you the size of their hands when they reach for you. It can be a quiet thing you offer to yourself so you can fall asleep without clenching your jaw.

On a rainy Tuesday, I sat across from Carmen Rodriguez in the same chair and signed the last set of documents. She watched me the way friends do when they’re pretending to be just doing their job. “How do you feel?” she asked, closing the folder.

“Light,” I said, surprised to find it true. “Like the first day without a cast.”

She smiled. “You did the hard parts. The rest is just walking.”

I walked. Through fall and into winter, through parades of umbrellas and the way the city’s neon looks softer in the wet. I developed rituals: Sunday dinners with Grace from the third floor, who had been married for twenty-nine years and taught me how to make pot roast in a slow cooker; Thursday night trivia at the bar down the block, where no one knew my last name; Saturday mornings at the market where the fishermen called out their prices like hymns.

Occasionally, I saw James around town. Seattle is small when you think it’s big. He would nod, and I would nod, and the air between us would stay empty and kind. We owed each other nothing. We had given back what we could, and the rest we had laid down.

On New Year’s Day, I stood on the ferry deck wrapped in a scarf that smelled like cedar and watched the gray water lift and fall. A man next to me pointed out a seal’s head, a small dark punctuation in the sentence of the Sound. I closed my eyes and pictured the line on my necklace: a wake, a fault, a horizon. I had not needed to be reasonable; I had needed to be brave. I had needed to tell the truth in a voice that sounded like my own.

When the ferry horn blew, deep and certain, the sound folded itself into my ribs and stayed there like a promise I could finally keep. I went inside and ordered coffee from the little counter, the kind they serve in white cups that always burn your fingers. I held it anyway. I watched a child press his hand to the glass and gasp when a gull rose up like a miracle. I felt the ship turn and, with it, the old story loosening, thread by thread, until all that was left was a woman in a warm coat walking toward a door, keys in her hand, certain the lock would open.

Sometimes, losing everything you thought you needed is the only way to remember what you truly deserve. Not because loss is noble, but because it is honest. It leaves you with the bones and the bright work of rebuilding. It leaves you with a bench by a window and a chain that holds a small, stubborn circle of gold. It leaves you with your own name said out loud in an empty room. It leaves you with a life that fits.

News

While the entire ballroom was applauding, I saw my mother-in-law quietly drop a “white pill” into my champagne flute — she thought I’d drink it; I swapped the glasses and smiled; she raised hers, the music jolted to a stop, every eye snapped our way — and that was the moment the wedding turned into an unmasking no one saw coming.

At My Wedding Reception, My Mother‑in‑Law Slipped Something in My Champagne—So I Switched Glasses I saw her hand hover over…

“My Dad Works at the Pentagon,” a 10-Year-Old Said. The Class Laughed, the Teacher Smirked—Ten Minutes Later, the Door Opened and the Room Went Silent.

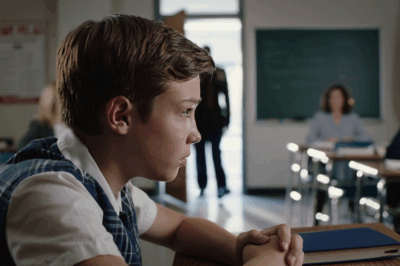

When the bell for morning announcements chimed through the beige halls of Jefferson Elementary, Malik Johnson straightened in his seat…

My dad dragged me across the driveway by my hair for blocking my sister’s car…

My dad dragged me across the driveway by my hair for blocking my sister’s car. The gravel scraped beneath my…

END OF IT ALL – I was told over and over again that I was not welcome at any family events. My mother yelled that events were for real family only.. So when I got married I didn’t invite them and they went crazy asking to fix things but I called such a call

I was taught early that belonging had rules nobody bothered to write down. You learned them by touch: a hand…

On My 29th Birthday My Parents Ignored Me And Sent My Sister To Hawaii — “She’s The One Who Makes Us Proud.”

The morning I turned twenty-nine, my apartment sounded like a paused song. No kettle hiss, no buzzing phone, no chorus…

My wealthy grandmother said, “So, how have you spent the three million dollars?” — I froze right there at graduation — and my parents’ answer silenced the entire family…

The graduation ceremony stretched across the manicured lawn like a postcard of American triumph—burgundy and gold banners, folding chairs squared…

End of content

No more pages to load