The courtroom smelled like polished wood and old paper—the kind of place where a story stops being gossip and turns into record. My boots were soft on the carpet, my medals steady against my chest, the flag behind the bench a measured rectangle of discipline. I stepped through the side door in full service dress and felt the inhale ripple the gallery, the slight change in temperature that comes when a room realizes it has misjudged you.

I didn’t scan the faces. I didn’t need to. I could feel my parents in the front row, dressed as if they were angling for a corner table at a club—my mother’s pearls making their tiny, brittle sound every time she moved; my father’s shoulders squared for optics, not truth. Beside them sat my sister, Emily—the family’s sun—already shaping a smile for whatever camera might find her first. To them I had always been the quiet one, the clerk, the daughter who chose stability because ambition didn’t fit. They never asked about the windowless office, the SCIF badge, the nights when numbers turned into names and I watched a map blink with lives like breathing lights.

It started as a joke at a backyard barbecue, the summer heat turning plastic forks into soft question marks. Emily, all gloss and timing, swung the conversation my way. “Sarah gave the military a shot,” she said, chin high with charm, “but she didn’t make it through training.”

I had a taped rib then and a nondisclosure agreement that would have swallowed my tongue if I’d unspooled an inch. All I could say was, “I can’t talk about it.” The sentence became my shadow—easier to repeat than to question, easier to pity than to see. By fall, the family narrative had hardened like poured concrete: I was dependable, small, and safely unremarkable.

“All rise,” the clerk called. Benches creaked. The judge entered, robe moving like a clipped flag, voice clear enough to cut marble. When the clerk lifted the mic and read the line that pinned the day to the record, the oxygen shifted.

“The Department of Defense is represented today by Major Sarah Collins.”

The name struck like a gavel. My mother’s hand flew to her pearls. My father leaned forward, as if squinting could unstitch the rank sewn above my pocket. Emily’s smile bent, a question without grammar. I rose, steady as drill, and said, “Ready, Your Honor.” The words didn’t have to be loud. Years gave them weight.

Opening statements found their rhythm and then blurred—numbers, codes, contracts, words like procurement fraud and misallocation moving through air as if the language itself had a clearance level. But when the prosecutor motioned toward me, the room straightened.

I began with the spreadsheets. Boring on purpose. Sterile line items, discreet funds, invoices designed to put a reader to sleep two cells in. Then I unrolled the map taped along my testimony: the arcs from contracts to shell companies, from shells to gear, from gear to failure. Photos followed—grainy black and white, classified once, projected now. Men and women in uniform. Some smiling. Some serious. All trusting. The silence broke not with sound but with weight, the kind that presses the air out of a room.

“This isn’t about dollars,” I said. “It’s about betrayal. We don’t sign up to die because someone saw a chance to skim.”

The defense tried the usual angles: impugn the motive, paint me as naïve, as vengeful, as a desk-bound idealist out of her depth. But all they did was hand me more drawers to unlock. I had lived in those files. Memorized the cracks in the paint. I answered with mission codes I had clearance for and operations I’d shepherded from shadows where a map is a heartbeat. Questions died in their throats. Pens stopped moving.

By late afternoon, sunlight had gone sharp through the high windows, thinning to blades along the bench. Emily stared at me like I was a stranger she should have known. When the final question landed and I stepped down, the judge leaned forward.

“Major Collins,” he said, each word deliberate, “the court thanks you for your service and for your courage.”

The verdict would come later, but the story had already shifted. Fraudsters would face prison; contracts would be rewritten. And my family—the keepers of a small tale about a small daughter—couldn’t return me to a footnote.

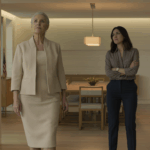

Outside, microphones bobbed like buoys. Flashes stuttered along the marble. My name ricocheted down the steps. Past the cameras stood my family, clustered like a memory: my mother’s mouth parted on a word that would not come, my father’s eyes wet—though he would never admit it—Emily’s arms crossed like she was bracing against weather.

“You called me a failure,” I said, quiet as a notch, not a blade. “But failure doesn’t wear these stripes.”

They didn’t answer. They couldn’t. And I didn’t wait.

People think the story ends on courthouse steps. Some do. Mine didn’t. The case was a hallway in a larger building. Open one door, find a dozen more.

Anonymous letters showed up first: notes tucked under my windshield wiper, messages slipped beneath my apartment door. Same all-caps handwriting, same ritual warning—STOP DIGGING. ACCIDENTS HAPPEN. I read them once and pressed them into a folder labeled with a date and a shrug. I upgraded my locks and switched my routes. The uniform, I reminded myself, is not a costume. It’s armor.

The media named me the Silent Major, which made me laugh in the shower when the water was too hot and I finally let myself have a noise. Silence had never been surrender for me. Silence was how you survived rooms where the only way out was to outlast the clock.

Then came the alley.

It was August in D.C., heat pulling the city into a soft blur. I was three blocks from a secure garage, my briefcase a perfect rectangle in my hand, when I felt the shift in the air that means a shadow is not a building. The footfalls were correct—steady, unhurried—but something in the pace tasted like training. I stopped at the edge of the alley and stepped into shade.

“Major Collins,” a voice said, low, not a question.

I didn’t go for the blade I wasn’t supposed to carry. I didn’t like paperwork you had to draft to explain a reflex. I turned.

He was taller than me by a head, thirty-five by the lines around eyes that were too alert to be retail. No badge. No rank. Posture that said muscle memory not gym. Plain clothes executed like a uniform.

“You’re making powerful enemies,” he said.

“And you are?”

“Someone who doesn’t want you buried before the truth comes out.” He handed me a flash drive between two fingers, a surgeon passing a scalpel across an invisible table. “Don’t use a government machine.” He smiled without teeth and was gone before I could cleanly decide whether to follow.

I didn’t take it home. I took it to a friend who owed me a favor and a couch. Jo had entered the Army a week after me, left two years earlier with a knee that clicked in weather and a gaze that could pick a lie out of a cloud. She taught herself to listen to computers the way she once listened to skies.

“Air-gapped,” she said, when I showed her the drive. “Firewalled like a submarine. And you’re not clicking anything. I am.”

We sat at her kitchen table with a laptop that hadn’t touched a network in years. Jo’s fingers moved like playing cards. When the first folder opened, both of us forgot to breathe.

Offshore accounts. Coded emails. A freight line of shell companies that ran like a river through boardrooms and out the other side into politics. The more we clicked, the less the original case mattered. It had been a pebble. This was a mountain range.

“You can’t turn this in blind,” Jo said, closing the computer with a soft violence. “Chain of custody, Sarah. If you walk this into the wrong office, it dies.”

“We go to the Inspector General,” I said.

“We go to two Inspector Generals,” she countered. “And a lawyer who can talk to a senator without getting hives.”

In the mornings I ran the river loop at Hains Point, easing my lungs open against the humidity, while my brain tiled what we’d found into shapes that would hold in court. I practiced answers out loud where the only witnesses were geese and a man in a sunhat fishing for anything that could remember cool water. The notes kept coming—now on heavier paper, now with postmarks that meant a hand had bought a stamp and stood in a line.

At work, the SCIF felt smaller. The windowless always does when you know a window would mean a sightline and a sightline would mean risk. Still, the work was the work: turn numbers into maps, maps into briefings, briefings into choices. Most days I left believing we put more good into the world than bad.

My parents called twice, each message a strange mixture of invitation and audit. “We had no idea, Sarah,” my mother said, the syllables tremoring. “How long have you been… well… a Major?”

“Since the spring after I stopped telling you things,” I said to the machine. I didn’t press send.

Emily tried to find me on camera, failed, and settled for text.

Can we do coffee? You were… amazing. I’m proud of you.

Proud landed in me like a nickel in a jar—small, metallic, a noise that took up more space than it should. I typed, I’m busy. I deleted it. I typed, Not a good time. I deleted that too. Finally I wrote, Rain check, and let it be a lie that hadn’t picked a date yet.

The first hearing after the alley felt different. Not just because of the senators—hair crisp, language rehearsed, phrases crafted to be quoted—but because of the air. It had that pre-storm headiness, the way humidity tastes like the word soon. When I swore in and sat, the ranking member asked questions as if he already knew where the answers would lead and was measuring my feet for the path.

“Major Collins,” he said, “you understand the risk of what you’re alleging.”

“I understand the cost of not alleging it,” I said.

They asked for names. I gave them evidence instead. Not because I was coy—but because a name without a chain of facts is a headline. I wanted law, not ink. We entered the drive into record through a sealed protocol that felt like handing a newborn to a stranger and trusting the hospital would do its job.

That night, a black SUV idled too long at the end of my block. I stood at my window and watched my own reflection watch the street. The SUV did what threats do when you don’t blink—it left.

I slept with my boots near the door and my phone on the floor so the light wouldn’t wake me if it lit. In the mornings, I ironed my uniform like prayer.

My father called on a Sunday, his voice lower, the way men talk when they’ve taken off the idea of themselves and are wearing the shape that fits. “Your mother wants everyone here for dinner,” he said. “Emily’s making that salad with the little oranges.”

“I can’t,” I said. “Security.”

A breath. “We didn’t know,” he said finally. “We should have.”

“I gave you the chance,” I said. “You chose a story that made you comfortable.”

Silence. Then, rawer: “Does it matter if we’re proud now?”

“It matters that you mean it,” I said. “And that you don’t ask me to make it easy.”

He didn’t. He only said, “Okay,” like a man learning a new language and trying desperately not to mistranslate the first important sentence.

The case grew teeth. Indictments started falling the way a line of dominos doesn’t so much fall as decide it always wanted to. The first arrests were mid-level—men who wore expensive watches with company polos and golfed their way into relevance. Then a colonel whose name had more decorations than quarrels on his wall resigned “to spend time with family,” and Washington did what it always does: it whispered, it watched, it waited.

Emily finally got me at a coffee shop by figuring out where law clerks went to pretend they were off-duty. I was in a corner with a cup cooling to the temperature of apology when she slid into the seat opposite me.

“You look different,” she said.

“I look the same,” I said.

“No,” she said, really looking. “You look… like yourself.”

We were quiet a moment. The shop had that low hum of people performing productivity like a spell. Emily pushed a strand of hair behind her ear, fingers trembling.

“I was awful to you,” she said all at once. “I repeated that line because it made me feel bigger. I didn’t want to look at my life and see that my big moves were small ones with lights on them.”

“I don’t want an apology you rehearsed,” I said. “I want one that costs you.”

“It does,” she said, eyes filling. “It will.”

We sat with that. I watched a barista pull a shot like he was wringing meaning from water. Emily squared her shoulders.

“What can I do?”

“Stop telling stories that make you the sun,” I said. “And when someone repeats the barbecue line, correct them. Loudly.”

She nodded like she’d been given a map and a pair of good shoes.

The notes stopped the week after the colonel resigned. Not because whoever sent them had changed heart, but because threat had ceased to be efficient. The play shifted. A leak dripped my address to a blog that sold outrage by the ounce. The comments came hot and then hotter. I turned off everything that dinged. I asked a friend to read me summaries like weather: carry an umbrella; avoid the bridge.

At work, a new director arrived with a handshake that measured grip and glance in equal parts. She read into my file like a good surgeon—steady, unflinching—and asked exactly one question.

“What do you need?”

“Time,” I said. “And a team that can’t be bought.”

She gave me both, plus an analyst named Rios who dressed like he owned fewer clothes than opinions and could pull a pattern from a blizzard with tweezers. Rios taped butcher paper to a wall and began sketching like the room had taught him to think in circles. Names linked to shells linked to projects linked to people who had done a great job of never being in the same photo as their own reflection.

“Follow the invoices,” he said, pencil tapping. “People can hide a face. They can’t hide the math.”

We didn’t go home early for six months. I learned the color of midnight in every conference room on our floor. Jo stopped by with Thai food and knee braces and the kind of laugh that cleans a room. My mother left Tupperware on my doormat on nights she would have once pretended she had plans. I found a note under the foil the second time—Proud is not the word, but it’s the one I can carry without crying.—and put it in a drawer where I kept things that didn’t need a label to be safe.

The second trial broke the country open for a week. The hearing room looked less like a chamber and more like a set piece constructed to be aired. Cameras hummed. Generals sat stone-faced in a row like statues that hadn’t decided which century to claim. Senators asked questions in sentences that remembered themselves while they were being spoken.

When I walked in this time, the silence had changed. It wasn’t surprise. It wasn’t suspicion. It was respect—and something stranger around the edges, as if the room had realized that some people you meet at the beginning of a story are still at the beginning because they’re building the rest.

I told it straight. We laid the paper like dominoes. We followed the money with the faithfulness of a dog and the patience of water. We pulled on a thread until a sweater that had always insisted it was a uniform unraveled at our feet. There were names too big to be said out loud and names small enough to be forgiven. We said them all.

On the last day, after a senator used the word rot in a sentence that did not include a metaphor, the chair asked if I had anything else to add.

“Yes,” I said. “We’re going to fix this.”

“Major,” he said carefully, “that is not a question.”

“No,” I said. “It’s a promise.”

You cannot legislate a promise, but you can make a room remember it.

The verdicts landed like weather fronts. Billion-dollar contracts were renegotiated; a handful were tossed into the kind of government fire that burns so cold you can barely see it. People I had only ever known as signatures on memos were escorted from buildings by men who did not smile. For a week, I couldn’t buy a coffee without someone paying for it first. I had never been more grateful for the anonymity of a baseball cap in my life.

On a Tuesday without rain, I stopped on my way home to watch kids play basketball on a court painted with fresh lines. A little boy in a neon shirt took a shot with terrible form and perfect faith; the ball smacked the rim and fell in anyway. He whooped so loudly the clouds laughed. I put my hands in my pockets and felt the quiet start to find me again.

That weekend, I went home for dinner. My parents’ house had the same smell it had always had: lemon oil and the clean cotton of a well-kept life. Emily was already there, sleeves rolled, actually making a salad with the little oranges this time instead of posing near one. My father hugged me like a man who had learned his arms were good for work besides lifting his own certainty.

We ate in the dining room we used to be told was for company. My mother lit the good candles. Halfway through, my father cleared his throat. Men clear their throats when the air is heavy with words they aren’t sure they deserve to say.

“I told someone at the hardware store you’re my daughter,” he said. “He knew your name before I did.” He smiled, tiny and true. “It felt like buying back something I sold cheap.”

I reached for his hand. We sat with that. It was not absolution. It was movement.

Later, on the porch, Emily and I watched the neighborhood lights find their familiar places. “You were always the brave one,” she said. “I was just loud.”

“I was scared every day,” I said. “I just didn’t let fear talk me into being smaller than my oath.”

We were quiet. Crickets sang the way they do when they don’t know a human is listening. Emily bumped my shoulder with hers.

“You know,” she said, “you can tell me things now… the things that can be told.”

“I will,” I said. “And I won’t use you as a mirror anymore.”

“Deal,” she said.

The next morning I woke to no notes under my door, no unfamiliar engines idling near the curb, no headlines trying to breathe on my behalf. I made coffee. I let the window be a window. I ironed my uniform because some habits are a way to tell your bones you’re still on your own side.

At the Pentagon the hallways felt like hallways again—just space between rooms, not a gauntlet. Rios had drawn a line through the last name on the butcher paper and written, in a handwriting that could have been a fight if it grew up: ACCOUNTABILITY IS A VERB. He shrugged when I looked at him.

“You said a promise,” he said. “I made a sign.”

We laughed. Then we went back to work. The work was never going to end. That was the point.

A reporter called, then another. They wanted a book, a movie, at least a magazine cover where I would stare down the lens like a woman who had never forgotten how to blink. I said no until I said yes to one paper that had covered the hearings like they were church: reverent about the truth, skeptical about the choir.

“What do you want people to remember?” the journalist asked.

“That courage is not loud,” I said. “And that a uniform is a promise you make to people who may never learn your name.”

He wrote it down like he was receiving a recipe he understood he would never fully recreate.

In December, a new class of lieutenants asked me to speak. I stood at a podium that had known a lot of speeches and tried to say something that wouldn’t calcify into a quote. “You will be underestimated,” I told them. “Good. Stay low enough to see the ground. You will be asked to move fast. Don’t. Move right. Speed is a drug. Accuracy saves lives. Write everything down. Tell the truth like it’s a muscle that must be used if you want to lift anything heavier than your own ego.”

They laughed where I wanted them to and listened where I needed them to. Afterward, a young woman with hair she’d obviously cut herself to comply with a regulation before a deadline shook my hand like she was remembering her grip while she used it.

“My family thinks I joined because I didn’t have options,” she said.

“Make sure they’re never wrong by accident,” I said. “But don’t set your life on fire to keep them warm.”

She nodded hard enough to dislodge a fear. I watched her go and remembered being her—a map folded into human shape, trying not to crease where love had already done the folding.

Winter came and made the city honest. The river looked like a sheet of thought someone had set out to cool. I ran less, walked more. I started leaving my phone in the other room at night. I bought a plant from a woman who told me its name like she was introducing a friend at a party: ZZ, indestructible. “You can forget to water it,” she said. “It won’t take it personally.”

I took it home and set it near the window. I watered it anyway.

On a Sunday, I drove to Arlington and walked the rows until I reached a name I knew in my bones. I told him what we had done and what we were still doing and how some days felt like victory and some felt like maintenance and how I had decided both counted. The wind moved the flag in soft, practiced shapes. I stood until the cold folded my hands for me.

On the way back, I stopped at a diner where the coffee is always better than the menu admits. The waitress called me hon without seeing the uniform under my coat and it felt like a blessing. When the check came, someone had already paid it. The note on the receipt said, simply, Thank you. No name. I smiled without my mouth and left a tip heavy enough to make gravity proud.

At home, I hung the uniform in light that did not need to be flattering to be kind. The medals gleamed like punctuation you don’t overuse. I sat on the floor because chairs felt like too much ceremony for the kind of peace I wanted. On the rug I practiced breathing without a mission attached to it. It felt like learning to occupy a room I had rented out to adrenaline for too long.

I thought of the courtroom—the first one—the polished wood, the old paper, the way truth sounds when it stops traveling as rumor and starts anchoring as fact. I thought of my mother’s hand at her pearls, my father leaning forward into a future he had not rehearsed, Emily’s smile fracturing into a face that could finally hold a new narrative without breaking.

They called me a failure. They called me quiet, small, safe. The names didn’t fit. They never had. Names don’t make us. We grow and the names either stretch or they split.

In the morning, the plant had aimed a new shoot toward the window. I laughed out loud, delighted by something that didn’t need my permission to reach.

I brewed coffee. I packed my bag. I looked at myself in the mirror long enough to remember that the person in the uniform and the person without it were the same one. Then I locked my door, walked down the hall, and stepped into a day that would ask me, again, to choose courage in small increments.

On the bulletin board outside my office someone had taped a strip of paper that said: FAILURE DOESN’T WEAR THESE STRIPES. It wasn’t my handwriting. I didn’t take it down. I let it be a reminder for anyone who needed it—including me on days when the fight looked like paperwork and the victory looked like silence.

The work went on. We audited. We trained. We turned processes that used to be soft into ones that could take a punch. People learned that if they siphoned a dollar from a rifle or a vest, there would be a name attached to that dollar, and the name would be theirs, and the light would find it.

At night, when the city hummed with the lives of people who had never once considered procurement anything, I walked past lit windows and let the ordinary save me: a woman watering a fern; a dad reading the same page of the same book three times because the toddler wanted the sound, not the plot; a student falling asleep over a laptop and waking with the imprint of a keyboard on his forehead. We fight for grand nouns—Country, Honor, Duty—but on the ground, what we protect is small and specific and glorious.

On a spring afternoon one year later, I ran into the judge in a grocery store aisle between pasta and possibility. He looked exactly like a man looks without a robe: human. He recognized me, then smiled like we were both off-duty from the performance of our titles.

“Major,” he said, nodding toward my cart, which held more vegetables than discipline would require. “How goes the promise?”

“Still keeping it,” I said.

“Good,” he said simply, and we went back to choosing the shapes we wanted to put in boiling water like it mattered (because it does).

When I got home, my phone buzzed with a text from Emily. A photo of her, hair wild, face bare, standing in a classroom with a dozen middle-school girls. She’d started a program that taught media literacy and ethics, and she looked happy in a way I hadn’t seen on her since we were kids eating popsicles on a curb that made our tongues red.

Proud of you, sis, she wrote.

Proud of you more, I answered, and meant it.

That night I sat on the floor again, back against my couch, the plant reaching for the window as if light were both habit and hunger. Peace was still new enough to be noticed. I thought of every room I had entered since that first day—the courtrooms, the hearing chambers, the conference rooms where fluorescent light made honesty look tired—and felt gratitude like a second pulse.

They called me a failure. Then I walked into court and told the truth. The truth didn’t make me taller. It just made the ground under my feet stop moving.

People ask what heroism feels like. I tell them I don’t know. I know what it feels like to clock in, keep your oath, and wear your stripes without letting them become your skin. I know what it feels like to be underestimated and to let that be a kind of cover while you build something better than a comeback: a standard.

In the morning, I’ll lace my boots, pick up my bag, and go back to work. Not because the story needs another headline. Because the promise still does.

I thought long stretches of quiet would feel like a prize. Instead, the first weeks after the verdict felt like stepping off a treadmill—I was still moving inside my skin while the world stood still. I kept working. The work kept me honest. But the story had poured gasoline on places I’d kept dry, and everywhere I walked seemed to whisper: more.

More came as an aftershock. A subcontractor with a last name that lived mostly on brass plaques declined to testify and then promptly found religion in a jurisdiction with no extradition. That told us we were pointed the right way. Rios and I split the load. He took the paperwork; I took the people. Paper lies less, but people tell you why the lies are worth telling.

The first door I knocked belonged to a warehouse manager who’d retired early and badly. He let me in because I didn’t flash my rank before he had decided I was human. We sat at a table nicked by years of meals eaten standing up. He poured sweet tea with ice that sounded like unasked questions.

“They told me to sign truck manifests I never saw,” he said, thumb rubbing a groove into the glass. “Said it was standard. Said I’d slow the mission down if I didn’t. You learn not to be the reason someone’s kid doesn’t get their dad back.”

“You were never that reason,” I said. “The people who built the system were.”

He nodded without looking up. “I thought if I moved fast, I’d stay clean.”

“Speed is how they hide the dirt,” I said. “We’re going to slow them down.”

The next week, the ceiling of my apartment exhaled dust when the upstairs neighbor moved out overnight. The landlord shrugged with an innocence that came dressed as a raise in rent. I packed anyway. I moved into a place near the river with sightlines I chose on purpose and neighbors who did not ask questions that began with what do you do. My mother insisted on helping. We argued about the number of towels one woman needs and then didn’t say the thing we were both feeling: that we were learning each other on new terms and we might not have the right words yet.

At night, I ran scenarios the way other people count sheep. The alley man had never reappeared. Jo said that meant he was either satisfied or dead. I told her not to talk like that. She told me to stop pretending we weren’t built in rooms where that sentence had already been true for other people.

“Do you ever miss the sky?” she asked, watching me iron a crease like it owed me money.

“I miss the quiet before you make a decision,” I said. “Not the part after.”

“Then choose something small tonight,” she said. “And enjoy choosing it.”

I chose to sleep with the windows open and let the river talk me into morning.

Senate staffers learned my coffee order and started sending me drafts that read like apologies. I did not rewrite speeches; I turned them back with notes that said, in effect: use verbs. Promise something measurable. Aim for a timeline, not a mood. If you want to be thanked, pass the bill.

The bill came out of committee with more teeth than I believed possible. Accountability is a verb, Rios had written. Now it had subclauses. A new funding checkpoint required independent audits at three points in the life of every high-risk contract. A whistleblower protection provision gained bones and penalties for retaliation that would make any executive read their policy manual twice. Watching it pass floor was like watching a bridge lower—the slow, dignified mercy of a pathway appearing.

Emily called from a school gym that smelled like old victories. “We held a workshop on how to spot misinformation,” she said, breathless. “Twelve-year-old girls are terrifying in the best way.”

“Good,” I said. “Teach them to be bored by lies.”

She laughed. “Come talk to them,” she said. “Not about the case—about being underestimated.”

I went. I left my uniform at home and wore a blazer that didn’t beg for attention. I told them no one gets to define the size of your life by the volume of their voice. We did an exercise where each girl wrote down a sentence she had swallowed and then we read them out loud and handed them back without commentary. The room shifted. You could feel the scrim of shame lifting, revealing something that looked a lot like capacity.

On my way out, a girl with braces and a backpack patched with national parks stopped me. “My brother says I can’t do math,” she said.

“You can,” I said. “Even if you choose not to. And if anyone asks you to show your work, show it to yourself first.”

That night, Jo came over with a pizza and a file. “This name keeps recurring in the metadata,” she said, dropping printouts on my table. “Never in the foreground. Always in the corner like bad wallpaper.”

The name belonged to a foundation that sponsored scholarships for children of service members. Rios traced the donations and found a shadow budget that moved in lockstep with overseas shipments of “technical consulting.” Consulting is a word you must never trust without receipts.

We brought it to the IG with chain-of-custody paperwork that would have made a prosecutor weep with relief. The IG assigned a team whose lead had eyes that said she had buried a lot of disappointments but had kept a shovel handy for hope. We met in a room that smelled like old carpet and coffee and the kind of intention that doesn’t need to be Instagrammable to matter.

“I can pull warrants,” she said. “But if this goes where I think it goes, you’re going to be the one standing in the storm again.”

“I brought an umbrella,” I said.

“Bring a boat,” she replied. “And a paddle.”

The raid hit three time zones at once. Warehouse, office, private home. We watched the returns populate in real time on a board that looked like a particularly earnest weather map. Jo tapped her pen against her teeth. Rios paced a six-step square that he’d clearly worn into the carpet over the last year. When the photos from the home address loaded, the room went quiet.

Basement. Shelves of boxes labeled by fiscal year. Inside, not paperwork but gear—spare parts meant for foreign allies stacked beside crates of comms equipment with inventory numbers sanded off. Next to them, a safe. Inside the safe, exactly what safe owners swear they never keep in safes: passports, cash, and a journal.

The journal was a ledger with thoughts. The best kind of confession is the one that doesn’t know it’s confessing. On page nineteen someone had written in neat engineer’s print: Pelican 14 rerouted. Handoff smooth. Gov inspector nosy (female). Keep eyes on Collins.

Jo swore softly. “Nosy,” she said. “They always call the people who notice things nosy.”

“Better than dead,” Rios said, eyes on the next page.

We executed arrests without giving anyone time to compose a press release first. Executives blinked like they had been woken by the wrong alarm. A colonel who’d been demoted six months earlier tried to make himself into a witness as the cuffs went on. That’s a trick older than uniforms. It didn’t work. The U.S. Attorney smiled the way women smile when they’ve waited a long time to do their job at full volume.

I didn’t call my parents. They had learned to read the news without calling me like I was an operator. Still, my father left a voicemail that said, “Save your energy for when it really matters.” It was the closest he had ever come to saying I love you in a sentence that recognized I might be too tired to carry it.

The morning after the arrests, a car bomb took the front end off a sedan parked three spaces down from mine. The blast punched the air and slapped me into the concrete like a hand that had forgotten I was not a nail. I heard people screaming before I realized one of them was me.

The fireball died quick. Someone had engineered spectacle not casualties. The firefighters who showed up moved with the muscle memory of men who had eaten breakfast expecting the day to throw a punch. Paramedics took my blood pressure twice because the first number told them I was either a ghost or the calmest woman alive.

At the station, a young officer asked if there was anyone he should call. “My boss,” I said, then, for once in my life, “and my mother.”

My mother arrived like weather you don’t check the forecast for because it’s inside your bones. She didn’t touch me until I nodded. Then she put her hands on my cheeks and said, “They can take our car door off, Sarah, but not our door.”

“You don’t have to make sense,” I said, and let her. Making sense is overrated on days when the universe is auditioning for a job it shouldn’t want.

The blast taught me what the notes had only tried to suggest: I was no longer inconvenient. I was expensive. We moved me into a temporary detail that shadowed me with the kind of professionals who look like someone your aunt might set you up with at a wedding until you notice they never put their back to glass.

“You will hate this,” the detail lead said matter-of-factly.

“I already do,” I said.

“Good,” she said. “People who like it are a problem.”

The hearings resumed with tighter security and looser tempers. A senator banged a gavel so hard the handle cracked and then tried to act like that had always been the plan. The defense attorneys had pivoted to a new strategy: paint the system as too complex to blame any single actor. That kind of fog is how institutions fail upward.

We countered with the kind of clarity a jury can write on a napkin. I kept my testimony mercilessly specific. When they asked me how I knew a shipment had been diverted, I gave them invoice numbers and dates and the name of the dock foreman who had lost sleep over it. When they asked me whether a certain executive could have been unaware, I said, “He signed a document three years ago that made him responsible. The privilege of authority is that it absolves nothing.”

After one session, the judge who had thanked me months earlier met my eyes across the room and nodded once, a small benediction. I didn’t know I needed it until I felt my shoulders drop a fraction of an inch.

That night I finally took my father up on dinner. He grilled steaks and over-seasoned the potatoes like a man who has always solved feeling with flavor. We sat on the porch where I’d once learned to tie my shoes and later learned to tie my tongue.

“I underestimated you,” he said quietly.

“You mismeasured me,” I replied.

He exhaled. “I taught you to be safe.”

“You taught me to be small,” I said, then added, because both were true, “and to be careful. One of those saved my life. The other one, I had to unlearn.”

He stared at his hands like they had recently done something noble without him. “Do you forgive me?”

“I don’t think forgiveness is a single event,” I said. “I think it’s a practice. Like excellence. Or sobriety. Or democracy.”

He laughed once, surprised. “You sounded like a senator just then.”

“Don’t insult me,” I said, and he laughed again, real this time.

Emily arrived late, hair damp, eyes bright with the kind of exhaustion you earn. She hugged me like our bones remembered the same childhood and asked if I wanted her to move closer to me for a while, just in case. “Your life is finally yours,” I said. “Live it near what you love, not near what you’re afraid of.”

She nodded, then broke into a grin that was all sister and no apology. “Fine. But I’m putting you on our program’s advisory board. The girls need you.”

“I’ll show up,” I said. “But they’ll need you more.”

We sat until the bugs declared primacy over the porch light and the night made promises to the neighborhood it would keep without witnesses.

In the weeks that followed, the case stopped being a headline and started being a syllabus. Universities called to ask for guest lectures. I sent Rios to half of them because he likes whiteboards more than audiences, and he came back with photos of students who had drawn process maps that actually improved ours.

The Office of Federal Procurement Policy issued new guidance with language so plain a contractor could understand it. The Inspector General published a report with a timeline that made it impossible for anyone to pretend this had been a surprise. One sentence from the executive summary went viral among people who have never once used the word viral about anything of consequence: Failure was not a lack of rules but a lack of refusal.

I printed it out and taped it inside my locker.

The last trial was smaller than the first—a courtroom without cameras, a judge who drank from a mug his kid had made in an art class where clay forgot about symmetry. The defendant was a mid-level manager whose mistake had been thinking the middle had no altitude. The middle is where you choose, every day, which way to lean.

When it ended, when the gavel sounded less like punishment than calibration, I felt something I hadn’t felt since my first oath: enough. Not forever. Not for everyone. But for now, in this lane, we had moved the needle. Enough that people who thought they could turn courage into collateral would reconsider. Enough that a woman in a SCIF somewhere, staring at numbers until they made faces, would know someone would believe her if she spoke.

I celebrated by doing nothing that would photograph well. I cleaned my apartment. I took the plant out of its too-small pot and gave it more room to want things. I read a paperback novel about strangers falling in love on a train and did not judge myself for underlining a sentence about the kindness of noticing.

In the morning, I stood in front of the mirror and practiced wearing my face without the story on it. Then I put on my uniform and remembered that the story and the face can be the same person without canceling each other out.

At work, a new analyst asked me if there was a secret to keeping your heart soft while doing a job that requires your skin to be thick. “You let yourself be moved by the right things,” I said. “And you stop expecting the wrong things to change your mind.”

“What are the right things?” she asked.

“Names,” I said. “Always names.”

On a warm night heavy with the smell of rain that had not arrived yet, I walked past the courthouse where everything had bent. The flag hung the way flags do when the air is trying to decide if it has something to say. I stood there a long time, boots on stone, breath even, and let memory be a visitor, not a tenant.

They called me a failure. And then they learned the difference between quiet and absent, between low and small, between polite and compliant. The country had learned a few things too. Not enough. Never enough. But something.

I went home. I put my medals in the drawer and left my uniform on the chair because tomorrow I wanted to see it and decide again. I turned off the light and lay down in a room that belonged to me—no ghosts, no notes, no agents parked at the curb unless they were on a date.

In the hush, I said out loud the thing I wish someone had told me the day Emily made that barbecue joke and the family wrote the first draft of me without my consent: They will misunderstand you right up until the minute they don’t, and none of that changes the work. Do the work anyway.

Sleep came like a yes earned honestly.

By the next spring, the audits had produced the kind of savings that make budget hawks act like poets. A general who had once preferred ceremonies to reforms took me aside after a briefing and said, “You gave me back something I thought I’d traded away: certainty that we can be better.”

“You gave it to yourself,” I said. “I just held the mirror.”

Walking out, I passed a line of new recruits, their haircuts too fresh to belong to anyone but the young. One of them, a woman with a scar bisecting her eyebrow like punctuation, caught my eye. She lifted her chin an inch—just enough respect, not an ounce of worship. I answered with a nod. We understand each other, the people who have learned to be underestimated on purpose.

At home, a letter waited in my mailbox with no return address and no threat inside. Just a single sheet of paper with four words printed in that same all-caps hand I knew better than my own in the dark: YOU WERE RIGHT TO FIGHT. No signature. No demand. No trap. I stood in my kitchen and let the relief be complicated. Maybe it was the alley man. Maybe it was someone I would never name. Maybe it was me, mailing grace to my own future from a past version I had refused to abandon.

I folded the paper, slid it into the journal I keep for days when the world asks me to explain my job to it, and wrote: Courage isn’t what you carry into court. It’s what you carry home when the room is empty, when the headlines are tired, when the people you love are finally learning to love you where you live. Then I closed the book, watered the plant, and set my alarm to wake up and keep a promise.

News

While the entire ballroom was applauding, I saw my mother-in-law quietly drop a “white pill” into my champagne flute — she thought I’d drink it; I swapped the glasses and smiled; she raised hers, the music jolted to a stop, every eye snapped our way — and that was the moment the wedding turned into an unmasking no one saw coming.

At My Wedding Reception, My Mother‑in‑Law Slipped Something in My Champagne—So I Switched Glasses I saw her hand hover over…

“My Dad Works at the Pentagon,” a 10-Year-Old Said. The Class Laughed, the Teacher Smirked—Ten Minutes Later, the Door Opened and the Room Went Silent.

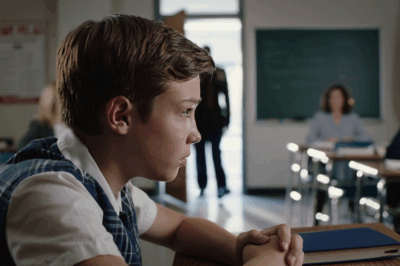

When the bell for morning announcements chimed through the beige halls of Jefferson Elementary, Malik Johnson straightened in his seat…

My dad dragged me across the driveway by my hair for blocking my sister’s car…

My dad dragged me across the driveway by my hair for blocking my sister’s car. The gravel scraped beneath my…

END OF IT ALL – I was told over and over again that I was not welcome at any family events. My mother yelled that events were for real family only.. So when I got married I didn’t invite them and they went crazy asking to fix things but I called such a call

I was taught early that belonging had rules nobody bothered to write down. You learned them by touch: a hand…

On My 29th Birthday My Parents Ignored Me And Sent My Sister To Hawaii — “She’s The One Who Makes Us Proud.”

The morning I turned twenty-nine, my apartment sounded like a paused song. No kettle hiss, no buzzing phone, no chorus…

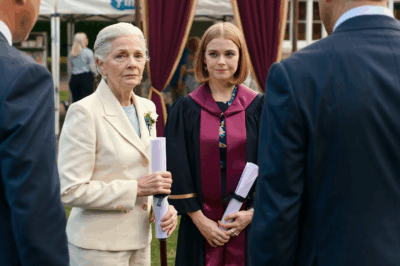

My wealthy grandmother said, “So, how have you spent the three million dollars?” — I froze right there at graduation — and my parents’ answer silenced the entire family…

The graduation ceremony stretched across the manicured lawn like a postcard of American triumph—burgundy and gold banners, folding chairs squared…

End of content

No more pages to load