I was taught early that belonging had rules nobody bothered to write down. You learned them by touch: a hand brushed away at the family photo, a chair nudged a few inches farther from the table, a phone that rang for everyone but you. If you didn’t dress right, talk right, make the family look good, you were background. You could be in the frame and still not exist.

I am Aubrey Linton. I grew up in a small Ohio town where summers smelled like cut grass and hot asphalt, where church bells taught the hour to the maples, where the same three families sponsored every parade and my mother sold the idea of us in a voice that never cracked. Our house wasn’t large, but on Christmas Eve she lit every candle like fire was proof of love. She could make a living room look like a magazine spread in twenty minutes flat and an apology last exactly ten.

At ten years old I learned to shrink. At twelve I learned not to knock. At seventeen I learned how to disappear.

The photo everyone praised hung at the bottom of the stairs: a picnic blanket in a county park, the four of us arranged by the logic of my mother’s eye. My brother sat center, sun flaring his hair into a halo. Dad knelt with a paper plate and a smile. Mom’s arm wrapped around my brother’s shoulders, her wrist in a tennis bracelet of someone else’s sisterhood. I’m there too. You can see me if you squint—knees pulled in, posture polite, a corner of the blanket claimed the way a guest claims a napkin.

“Everyone smile,” Mom sang that day, the camera counting down. When the picture clicked, I thought—maybe this time. Maybe her arm will find me.

It didn’t.

The first time anyone said the quiet rule out loud, it was late November, gray light pressing itself against the kitchen window while Mom basted a turkey like she was painting it. I was seventeen and still wearing the choir dress I wasn’t allowed to perform in because my hem wasn’t right. A cousin had turned seventeen the month before and gotten flowers and a cake, a speech about “our bright girl.” I got the midnight shift at the sink, my hands in water until the pads of my fingers softened and shriveled.

“Thanksgiving’s just family this year,” Mom said without looking up.

“I’m family,” I whispered.

She salted the bird like she was warding off more than decay. “Don’t make this difficult, Aubrey.”

If I didn’t dress right, talk right, make them proud, where else was there to go? That winter I started hiding in the house: attic corners that held the heat of summer like a promise, the basement room with the broken treadmill and boxes labeled CHRISTMAS LIGHTS and AUBREY’S SCHOOL THINGS. The labels never matched: the lights worked; my school things had been thrown away.

When I was nineteen and the air smelled like wet cardboard, I came home with a suitcase and a plan. I was going to apologize—for being poor at the pageant of our family, for not getting into the college my mother could brag about, for the haircut that made me look like a girl who didn’t know her place. I climbed the porch steps and rehearsed a sentence: I’m sorry, can we talk?

The door closed before the sentence found breath. The porch light cut me in half: the stranger outside, the daughter within. Mom stood with her palm on the wood between us.

“You’re not welcome here anymore,” she said. The way some mothers say, I love you. Final. Practiced. A line she’d rehearsed for days in the mirror.

When I didn’t leave, an hour later an eviction notice bloomed under a strip of blue painter’s tape, the kind you can rip away with your bare hands. The paper trembled in the winter air. The police lights came, polite and embarrassed, red and blue knitting themselves into a warning on the snow.

“Ma’am,” an officer said, handing me a card with a hotline on it. “Is there someone you can call?”

There wasn’t. Not then. I slept in my car and promised myself a life where belonging wasn’t borrowed.

I left Ohio with everything I owned on the backseat and a job offer in Portland I’d gotten from a favor of a favor. The drive west unfolded like a Bible story: deserts and mountains, towns where no one knew my last name, places that looked nothing like a magazine spread and everything like a map to myself. Somewhere past the Dakotas I stopped wanting to turn around.

In Portland, the sky began and ended in rain and bridges. The city’s bones were steel and green paint. People said hi on sidewalks without checking your shoes. I rented a studio that smelled like old wood and coffee, met neighbors who brought soup when the flu found me, found a job where “marketing” meant telling small truths well. I learned the names of the bridges the way you learn the names of saints: St. Johns with its gothic bones; Morrison’s practical lift; Hawthorne, dear and old. I watched joggers on the Eastbank Esplanade and felt my lungs open.

By then I had learned to be quiet about survival. I bought a thrift-store coat and a new pair of boots, the kind you can weather a city in. I went to a bookstore and stood with my fingers on the spines until I found a sentence that said the thing I needed: You get to leave.

That’s where Eli found me, in a line for coffee that curled like a question. He asked the kind you don’t hear much: What’s your favorite place nobody else loves? I told him about the corner table in a bakery with a dented tin ceiling, a table that caught a trapezoid of sun around 3 p.m. in winter. He told me about a library with windows like ship’s portholes. He was a quiet man with a laugh you could trust. His shirt sleeves rolled the same way every time. He didn’t reach for me like I was a story he needed. He asked if I wanted a cookie and then he listened to the answer.

We dated backwards, talking about the things we were trying not to be long before we touched the things we could become. When he learned about Ohio, he didn’t ask why I didn’t fight harder; he asked how long I had been tired. I told him the truth and watched how he held it. He never used my pain for light.

He proposed under the rain-lit hawthorne Bridge downtown, a ring in his pocket and rain in his hair. “You can say no,” he said, which told me everything I needed about the yes. I answered before he found the end of the sentence.

We planned a wedding with twenty-eight chairs and a promise to invite only people who knew us, not people who’d claimed us. I made seating cards on the kitchen counter in our apartment, each name a little door I actually wanted to open. The quiet inside me felt like a meadow that had finally grown back after fire.

Then the ghosts tried to RSVP.

It began with my cousin Danielle’s voice note, all vowels sugared like an apology you don’t mean. “You really think you can cut everyone off, Aubrey? They’re furious. You better fix this.”

By afternoon my phone was a parade of the old rule made loud. Mom: You’re being childish. This wedding is a chance to heal. Dad: You think you’re better than us now. My brother: You’ll regret this stunt. The word they loved to throw at me came dressed as concern: unstable. The family group chat, which I had been quietly removed from years ago, found my number somehow and then found it again. The messages stacked themselves like a filing cabinet no one would ever read.

I didn’t reply. But the muscles memory of fear woke up anyway, a crawl up the spine. Years of being told that love was conditional can make a phone glow like a summons.

Eli found me on the floor, my back against the cabinet, thumbs hovering over bile. He knelt until his knees found the tile and rested his hand beside mine without touching. “You don’t owe anyone an invitation to your peace,” he whispered.

I exhaled a breath I hadn’t noticed I’d been holding since childhood.

Curiosity, if not cruelty, finally pried open one voicemail from my mother. Her voice had that practiced tremble. “Aubrey, you’ve always made things difficult. Your father’s embarrassed. If you just apologize, we could fix this before people start asking questions.”

Fix this. The phrase clicked a lever in me, the one that controls the threshold between being a child and being grown. Fixing, in our family, meant absorbing blame so the story stayed tidy. It meant me, again, stitching their reputations with my silence.

I stood up. I poured myself a glass of water that tasted like a decision. Then I opened my laptop and wrote an email to the entire list of relatives whose addresses I could find—not even the ones I liked, just the ones who would forward it with a gasp. It wasn’t long. It wasn’t a defense. I scheduled it for the morning of my wedding, so there would be no last-minute negotiation, no room for them to make a spectacle in real time.

I wrote: I forgive you, but forgiveness doesn’t mean access. Some doors close quietly, others permanently. This wedding isn’t revenge; it’s release.

The morning sun spilled across our apartment, touching the lace of my dress draped by the window. My phone buzzed with the sort of urgency people reserve for house fires and gift registries. I turned it face down. Somewhere in Ohio, I could almost see my mother opening the email, narrowing her eyes like she was reading a price tag in bad light.

“You good?” Eli asked from the kitchen, holding two mugs of coffee.

“Better than I’ve ever been,” I said, and meant it.

We married under a canopy of fairy lights in a garden that smelled like wet soil and roses, the rain holding itself at the edges of the sky like a courtesy. Leah, my best friend, adjusted my veil and whispered, “You look like peace.” I believed her, which surprised me like a bench you didn’t expect to hold your weight.

Halfway through dinner Leah’s phone buzzed. She frowned and slid it across the table toward me, face open with the kind of concern that isn’t performative. “Aubrey, your mom just posted something.”

I didn’t want to look. I looked.

A photo of me as a child, a caption in the voice of a martyr. Some daughters forget who raised them. Sad day for our family, but love always wins. The comments bloomed like mold: cousins who hadn’t spoken my name in years were suddenly in mourning; church friends performed pity with a discipline usually saved for fasting. Someone called me ungrateful. Someone else suggested prayer.

Eli leaned in. “Don’t let them steal your moment.”

I smiled for the next photo and swallowed for the next three hours.

The morning after the wedding, the world should have been hushed as a church pew after the service. Instead, my feeds looked like a stadium had decided to preach to me. A community group had picked up my mother’s post. People were tagging me under my maiden name as if that word could drag me back through a side door.

Aunt Janice texted. Aubrey, people are saying you’re unstable. Maybe apologize and move on. Family’s all you’ve got.

Unstable. She’d chosen the word on purpose. It was the same one Mom had used when I left at nineteen, suitcase in hand, her tears accurate to the performance if not the cause. Not grief—control slipping.

I took my phone to the balcony and let the cold pierce my bare feet until it clarified something in me. Down on the street, buses moved people to the lives they had chosen. I used to think I needed a witness to my leaving. It turns out you can write your own affidavit in a breath.

“I’m not fixing it,” I said when Eli came to the door. “I’m finishing it.”

I called Claire, a woman I’d met on a campaign where I’d tried to make a bakery’s cinnamon roll sound like a sacrament. She did crisis PR for companies and people whose messes didn’t leak but flooded.

“You still handle social cleanups?” I asked.

There was a smile in her voice. “Whose mess are we erasing?”

“Mine,” I said. “But not how you think.”

I forwarded the post. She didn’t need a glossary. “Classic manipulation campaign,” she said after a beat. “Give me a few hours. I’ll trace the accounts pushing this and see who’s feeding them.”

When she called back, the flowers from our ceremony were still drinking from vases on the windowsill. My veil lay folded like a napkin on the couch.

“You might want to sit down,” Claire said.

I stayed standing. “Go ahead.”

“It isn’t random. Your mom’s been sending screenshots and emails to a local blogger who runs a gossip site about family drama. She sent private photos. They’re prepping an article.”

My throat went dry in a way I thought I’d outgrown. “She’s trying to ruin my name.”

“Not if we get ahead of it,” Claire said. “Do you still have documentation from when she, uh, asked you to leave? Anything official?”

I did. I had saved the eviction notice with the painter’s tape still stuck to the corner. The text where she told me to get off “her property” like my childhood had been a rental. The police report she filed claiming I had threatened her so she could craft a narrative with a paper trail.

“Send everything,” Claire said. “We’ll build your side. Calm. Factual. Professional. No anger—just receipts.”

I scanned the papers at our dining room table like I was giving evidence to the better version of the world. Then I wrote something I’d never written for my family before: a letter that didn’t beg. I sent it with the documents to the same blogger my mother had used. I wasn’t asking for pity. I was asking for fairness and the kind of quiet you can’t counterfeit.

The blogger responded with a politeness I hadn’t expected. We’ve reviewed everything. Thank you for trusting us. The story will be updated.

The next morning the headline learned its own lesson: Daughter speaks out: Family lies, love, and the price of silence. The comments shifted like a tide turning. A stranger wrote what I had been trying to teach myself to believe: Love is not the same thing as access. Someone else wrote: Sometimes the healthiest family boundary is a locked door.

By noon, my mother’s sympathy tour began to collapse under the weight of her own words. By sundown my inbox held nothing I felt compelled to answer. The silence was different now. It felt earned.

Mom called the next morning from an unknown number, the way salespeople and old lovers do. I let it go to voicemail. Her voice shook, but not with grief. “You had no right, Aubrey. You embarrassed this family. Your father’s humiliated. You’ll regret this.”

The line might once have landed on the softest part of me and made a bruise. I listened again and felt nothing except the sensation of a zipper closing.

I made the call I’d been saving. “Grace? It’s Aubrey.” Ms. Reynolds had represented me years ago when I needed a judge to tell my mother to stop standing in my apartment hallway like a sentinel. “I need to update terms on that old order. They’ve crossed a new line.”

Grace’s voice was the legal version of a good sweatshirt. Warm. Worn. “Forward everything,” she said. An hour later, she had assembled the digital trail: the defamation posts, the mass-tagging, the leaked photos. “You’ve got a solid case,” she said. “This moved from family drama to digital harassment a while back. I’ll draft a cease-and-desist and an intent-to-sue for defamation and intentional infliction of emotional distress. We don’t have to file today. But we will be ready.”

I signed electronically. She sent the notice to Mom, Dad, my brother, Aunt Janice, everyone who had helped carry the match to the tinder and then acted surprised when something burned.

An hour later a text arrived from my father, the most he’d said to me in five years. You didn’t have to go this far.

I typed, deleted, typed again. What I sent was the truth with its coat off. You should have stopped her before I had to.

After that: nothing. No calls, no comments, just the stillness of a bridge finally burned behind you and the kind of wind you feel on the other side.

Two weeks passed. The world forgot to pity my mother. Public sympathy has an expiration date; it spoils faster than milk when it’s exposed to facts. A cousin told a cousin told a neighbor: Mom had deactivated her accounts after the blogger posted a clarification with receipts. Dad retreated into whatever quiet he’d cultivated, which was always more like avoidance than contemplation. No apologies arrived. None were owed.

I turned the volume down on my curiosity and turned up my life. We took a small honeymoon along the Oregon coast where the ocean breaks itself for miles and no one calls it drama. We ate chowder and watched teenagers jump from rocks into water that would be too cold to survive, as if the miracle of youth is the ignorance of its ending. We came home with sand in the car and salt in our hair and slept like we had signed a treaty with our own hearts.

Sometimes at night I would wake to the shadow of a thought shaped like my mother’s voice. It would say my name the way she said it when I was a child: drawn out, like a note in a song only she could hear. I lay in that dark and listened until the voice thinned and the new one, the one that sounded like me, spoke instead. Love doesn’t beg, it said. Love stays.

While unpacking a box of books for the new apartment that felt like our first deliberate room, I found the picnic photo tucked between paperbacks. For a heartbeat I wanted to keep it, to pretend that sunlight and grass could bless what stood out of frame. Then I looked at the geometry of the thing—how my mother’s arm fit only one child, how the camera had obeyed the rules of our house without anyone needing to say them.

I slid the photo into an envelope and wrote Grace’s office address. KEEP FOR FILE, I wrote on the back. A reminder of where it started.

Claire emailed to say she could post a final public statement on my behalf now that the dust had settled. I stared at the draft she’d attached, the kind of paragraph that ties a bow meant to be cut immediately. Thank you for respecting our privacy. We ask for grace. I deleted it. Some endings don’t need an audience.

But there was one last conversation I owed myself. It wasn’t with my mother. It wasn’t with anyone who could answer back.

On a gray Sunday after rain had washed the city of its dust, I rented a car and pointed it east. The interstate memorized my tires like an old song. I passed the same towns I had left behind, their water towers stenciled with mascots and pride. Coming home did not feel like coming back; it felt like visiting a museum where a curator had mislabeled everything on purpose.

The house was smaller than the version I kept by mistake. The shutters curled. The porch sagged like an old argument. A FOR SALE sign tilted in the yard, the white rider at the bottom boasting NEW ROOF as if a new lid could change the contents of a jar.

I didn’t knock. I owed the door nothing. I had in my pocket a single envelope addressed to no one. Inside was a copy of Grace’s notice, not because I wanted to threaten but because I wanted to file with the universe my final statement. On a notecard I wrote in my smallest, neatest hand: I release you. Not for you, but for me. This story no longer owns me.

I slid the envelope through the mail slot where I used to listen for the soft thud of catalogues and credit card offers. The sound was the same. Everything else was different.

Rain began with the kind of gentleness we mistake for mercy. I stood under it until my hair clung to my cheeks, until the cold soaked me enough to feel new. Then I walked back to the car without looking up at the small dormer window where I used to keep a plant that refused to bloom.

My phone buzzed. A text from Eli: You good?

Yeah, I typed. It’s done.

On the way out of town the stoplights blinked red like old warnings trying to be relevant. The grocery store still had a display of seasonal pies in the window. A boy in a letterman jacket laughed like the future would always open for him. I didn’t feel envy. I felt distance, which is not punishment but space.

Back home I placed a wedding photo on the shelf. Not the one a photographer edited for social media—the one where my veil had caught on the heel of my shoe and I was laughing into Eli’s shoulder because I could not believe how immediately happiness asks for nothing. The frame was cheap. The moment wasn’t.

Sometimes healing doesn’t sing. It sits. It pays bills. It locks doors in the evening and doesn’t flinch at footsteps in the hall. It weeds the tiny squares of dirt on a city balcony and learns the names of the things that grow there. It buys a rug. It makes dinner at the same time every Tuesday, a ritual of warmth we call ordinary because we don’t have a better word for sacred.

One night in September, months after the quiet had taught me its shape, I woke to a sound that wasn’t the past this time but a branch scratching the window like the smallest visitor. I got up, pressed my forehead to the glass, and watched as the neighborhood cat patrolled the alley like a cop no one asked for. I smiled and went back to bed and tucked my feet into Eli’s calves, heat finding heat.

“I keep waiting for the other shoe to drop,” I said into the dark.

Eli, already half-asleep, said, “Maybe this is a house without that kind of shoes.”

In the morning I made coffee and didn’t check my phone. I watered the basil and wiped the kitchen counter and straightened the stack of mail held by a magnet shaped like a pear. When I finally picked up my phone there was nothing from Ohio. The silence wasn’t a threat. It was proof.

Weeks turned into the kind of life I always thought belonged to other people. We bought crates at a hardware store and labeled them with a marker I liked the feel of. We argued once about whether a lamp belonged by the couch or the bookshelf and then laughed because we could argue from safety now. Leah came over once with brownies that failed spectacularly and brought them anyway. We sat on the floor and ate them with spoons and called it good.

Dad texted once on a Sunday. No subject, no lead-in, just a photo of a yard sale where a painting leaned against a table. The painting was of a barn that never existed in our town. He had no words for me, and I had none for him. I refused to perform outrage or forgiveness. The text scrolled into the past like a receipt for something you didn’t buy.

Aunt Janice sent a Christmas card with a picture of a wreath on a door that wasn’t mine. Inside: Praying for reconciliation in the new year. No return address. I set it on the counter and walked my fingers over the embossed berries and felt nothing rise.

Mom did not call again. Not at Christmas. Not on my birthday. Not when the blogger published a small correction months later attaching her emails like ornaments to the truth. Her silence became its own weather. I learned to carry an umbrella and then, eventually, to love the rain without one.

On a Saturday morning when the market finally had Washington cherries cheap enough to buy two bags, I stood at our sink and stained my fingers red and thought about the first line of my email to the family on my wedding day. I forgive you. I had meant it then and I meant it now, which is different from letting a person back into the house they once set on fire. Forgiveness, it turns out, is my coat. It keeps me warm. It’s not a blanket I throw over anyone who wants to come inside.

That afternoon I sat down with a notebook and wrote a list titled: Things I Will No Longer Apologize For. It wasn’t performative. No one would see it but me. I wrote: Saying no. Saying yes. Not visiting Ohio. Changing my name. Keeping my name. Blocking numbers. Not replying. Leaving group texts. Refusing to tell a story that paints my mother as a villain because that also paints me as a child. Loving a man who doesn’t need me small. Loving myself big.

I tore the page out, folded it, and slid it into the drawer where we kept stamps and the spare keys to a house that knew the sound of me coming home.

At night now I fall asleep without waiting for sirens. The door locks click, and the sound means safety, not hiding. The stories I tell myself begin with the sentence that always changes everything: You get to leave. And because I left, I get to stay—here, in this life I have made on purpose, where the only rule that matters is the one I finally wrote down: Love is welcome. Control is not.

The last time I went through the old mail I had forwarded from my first Portland apartment, I found a postcard from that bakery with the dented tin ceiling. They’re closing, it said. Thank you for letting us be part of your morning for twelve years. I stood in our kitchen and let the truth slip in: some things end without apology and still matter forever. You can grieve honestly and move on clean.

On our anniversary the rain came back like an old friend. We walked the waterfront and stopped in the middle of the bridge and kissed like people who owed nothing to ghosts. We went home and ate noodles and watched a movie about people braver than we are and fell asleep on the couch in a tangle of legs and easy breath.

Around midnight I woke and carried the plates to the sink and turned off the lights and stood in the dark of our living room, the kind of dark that doesn’t ask you to explain yourself. The city made its small noises like it was tucking itself in. I walked to the front door and turned the deadbolt until I felt it seat.

This time, when I locked the door, it stayed closed for the right reasons.

And in the quiet that followed, I heard only the sound of my own life answering itself back.

In the weeks that followed, that sense of rightness—like a door closing against wind—didn’t disappear. It settled. I noticed small proofs that a life can be both ordinary and holy at once: the rhythm of the Max trains, the way the street outside our building filled with dog-walkers at dusk, the neighbor with the baseball cap who always said, “Evening,” like it was a spell. I began to test my new boundaries in tiny ways I could keep. If a number I didn’t recognize called after ten p.m., I let it ring. If a memory arrived dressed like nostalgia and tried to sell me a softened version of the past, I said no to the door-to-door salesman in my head and went back to stirring the soup.

But endings—real ones—ask you to make room for the history that forged you. So I wrote. Not an essay for the internet, not a letter for the lawyer, but the story only I could tell myself, the one that began before the eviction notice and the painter’s tape.

I wrote about the Ohio July when I was ten and the county fair set up its ferris wheel like a prayer you could climb. Mom braided my hair too tight and told me to keep my knees together when I sat. Dad won a goldfish for my brother with a single toss, and I held a paper cone of lemon ice that dripped down my wrist like forgiveness you could lick. A woman from church told Mom I was getting “broad in the hips,” and Mom laughed like compliment and warning were the same word. On the ride home, she rolled down the windows for my brother and told me to hold my hair so it wouldn’t tangle—as if freedom was a thing that only ruined you if you didn’t control it.

I wrote about choir tryouts freshman year when I sang second soprano and watched the director’s eyes skip me like a stone over a flat lake. “Projection, Aubrey,” she said after my turn, and then turned away before I could ask what that meant. I learned to sing loud in empty rooms and quiet in full ones. Projection, in our house, meant how well you reflected my mother back to herself.

I wrote about the day I found a note in my locker that said, in careful block letters, You could be great if you wanted. No signature. No follow-up. I folded the note into the pocket of my jacket and wore it like a talisman for two winters. Some kindnesses are anonymous because the giver understands how dangerous debt can feel when you’ve only known the kind that collects.

I wrote about Mrs. Whitaker, our neighbor with the maroon station wagon and wrists like twigs. When I was twelve, she let me stand on a stool and stir the pot of chicken and dumplings she called “company stew,” even when no company came. “You don’t have to be hungry to earn a bowl,” she said, which was news to me. Once, when Mom grounded me for speaking “out of turn,” Mrs. Whitaker called me over to help hang laundry on her line and told me a secret: “Sometimes you have to borrow a house to remember what home is supposed to feel like.” When she moved to Florida the summer I turned fifteen, she left me the stool. I kept it until the day I packed my car for Portland. I still miss that stool like a person.

I wrote about the night at nineteen when the police car idled in front of our house and I held my suitcase and the officer’s card and learned that a person can be removed politely. How Dad stood behind Mom, eyes wet and useless, and said nothing. How I drove to the river and slept in the parking lot of a twenty-four-hour gym because the sign made the night look like day. How I woke up with a backache and a certainty that my life would be built out of my own tools from then on.

Then I wrote about Portland again, because remembering only the hunger can make you forget that you’ve since eaten.

The studio apartment on SE 26th had a slanted floor that made the chair drift slowly back from the desk if you weren’t paying attention. The windows were painted shut, and the first time heat arrived it stayed. I learned where to stand to catch a breeze through a hallway vent, learned which laundromat machines ran too hot, learned that the man at the corner bodega would sometimes slip a bruised apple into my bag and pretend it was an accident. On Saturday mornings, I walked to the farmers market and stood by the musician who always played a song with a chorus that sounded like home, even before I had one.

Leah came into my life in an office with terrible overhead lighting and a bottomless snack basket. She worked two desks over and said “good morning” like a dare to be a person. When my first campaign failed because the client insisted their brand could be both luxury and bargain, Leah took me to a food truck that served grilled cheese like an apology to every bad decision you’d ever made, and said, “You’re good at the part that matters.” We were friends by the end of the sandwich. Later, she would stand behind me on my wedding day and tuck a rogue strand of hair into my veil like she was fixing something bigger.

Eli and I had our first argument on a hike in Forest Park about whether it was okay to take a shortcut he swore was a path. “If it isn’t, we’ll just make a new one,” he said, and I stopped, heart louder than the creek, and said, “I have made too many new ones by myself.” He understood. We stayed on the trail. On the drive home, we didn’t fill the silence with explanations. When we reached the city, he took my hand at a red light and squeezed once like punctuation. The light changed, and so did something in me.

We built a life in the small gestures of people who know what it costs to tell the truth. He did the trash without mentioning it. I learned the sound of his footsteps and which ones meant he’d had a day. He told me about his father who left when he was eight and the way his mother worked double shifts and never once said she was tired. I told him about the picnic photo and he smoothed the memory with his palm as if it were a wrinkled shirt and he could wear it for me for a minute so I didn’t have to.

When he proposed on the bridge, it rained in the particular Portland way that makes even the cars quiet. He said my name like it was a promise he intended to keep. We kissed, and a jogger clapped as he passed like we were the cause of a good weather pattern.

I remember the first night after the legal notice went out, the way my body slept like it had a new border. I dreamed of a house with windows that opened and a mother who asked how my day had been and meant it. I woke up and made coffee and didn’t cry. Progress is sometimes measured by the minutes in a morning.

Grace called a week later to say she’d heard back from my mother’s attorney: a local man whose last name sounded like a door closing. “They’re offering to take down all posts and issue a generic statement about miscommunication,” Grace said, “if you agree not to pursue damages.”

I watched a bird land on the porch rail, head cocked like a question. “I don’t want their money,” I said. “I want the quiet I’ve already built. But I want it protected.”

“Then we add a non-disparagement clause,” Grace said. “No more public or semi-public commentary about you, your marriage, your mental health, your alleged obligations to the family. If they violate it, we file.”

“Do we need to sign anything?” I asked.

“You already did,” she said, and in her voice I heard a future in which I didn’t have to be the one to carry every paper on my own.

By the time we “settled”—which is a strange word for a thing that simply stops—my mother’s sympathy post was three algorithms old. The internet had found a new outrage to feed. The silence afterward didn’t feel like a cliff. It felt like a field.

One afternoon in October, I got a letter without a return address. Inside was a recipe card in my grandmother’s handwriting: molasses cookies written in the cursive of a woman who learned to write when penmanship meant something. I held the card like an heirloom and then I looked for the trick. Was this a breadcrumb trail back to the porch? I put the card in an envelope and mailed it to Grace to keep with the file, because safekeeping isn’t the same as clutching. Before I sealed it, I copied the recipe. Some inheritances you’re allowed to keep.

That winter, I adopted a cat who chose me at the shelter with the indifference of royalty. He was gray and opinionated and stationed himself at the window like a sentry. I named him Hawthorne because I liked the sound of a bridge keeping watch over a river and because symbols should earn their keep.

Leah went through a breakup that left her looking like she had been rearranged by a storm and the interior designer forgot to come back. She slept on our couch for three nights and drank tea from my favorite mug and said, “I don’t know who I am without him,” and I said, “Let’s make a list,” and we did. We wrote down: Someone who returns carts in parking lots. Someone who texts back. Someone who laughs at the right parts of a joke because she was listening to the setup. Someone who has survived worse than this. She taped the list to her fridge when she moved into a new place, and sometimes when I visit, I read it again like a mirror.

The holidays arrived, as they always do, with their pageant of expectation and light. We hosted a small Friendsgiving with folding chairs and a turkey that tasted like YouTube had taught us how to be adults. I made mashed potatoes, because I know my way around starch, and Leah baked a pie that looked better than it tasted and no one told her. After dinner we went around the table and said one thing we were learning to do without apology. A nurse said, “Sleeping.” A teacher said, “Not grading on weekends.” Eli said, “Letting people help me.” I said, “Ending things without an explanation.” No one argued. No one asked me to recant my joy for their comfort.

Work became a place where I could make things that didn’t hurt anyone to hold. Claire called me in December with a proposal. “You’ve got a knack for the human part of hard narratives,” she said. “Come consult, occasionally. Help clients tell the truth without burning down their lives.” I took on two projects. One was a family-owned flower shop whose matriarch had posted a rant about a customer and realized too late the customer was the high school principal. We drafted a statement that began, simply, I am sorry and ended with We will do better because that is the only useful ending. The other was a nonprofit with a volunteers-gone-bad problem. I wrote them a guide about boundaries and posted it in the staff kitchen. Someone underlined the sentence, You can be kind and say no.

Eli and I started talking about opening a small studio, the kind that does good work for small businesses that have more heart than budget. We argued for a week about the name and then chose one in the three minutes before a parking meter expired: Lantern & Bridge. Later, I realized that what we had actually named was the life we wanted to build: light, connection, a way across.

In March, I saw Danielle’s name light up my phone for the first time in months. I let it go to voicemail. Her message was shorter than her old sermons: “I’m sorry. I didn’t understand. I won’t ask for anything. Just—congratulations. Your wedding looked beautiful.” It was the first sentence she’d ever sent me that didn’t contain an instruction. I texted back two words that owed her nothing: Thank you.

Sometimes the past tries to come back wearing a disguise that isn’t fooling anyone. In April, a woman from our old church reached out on a new account and asked if I would consider “reconciliation counseling,” as if there was a coupon for it you could send to strangers. I forwarded the message to Grace and then blocked the account. In the afternoon, I watered the basil.

And then there was the day in May when my father called and I answered without thinking because the muscles in a child’s hand remember the shape of a phone even after the hand belongs to a grown woman. “Aubrey,” he said, and his voice had more years in it than I remembered. “Your mother is…she’s not well. She’s moving to be near your aunt. I thought you should know.”

“How do you want me to respond to that?” I asked before I could pretend to be softer than I am.

“I don’t know,” he said. “I’m sorry. For everything I didn’t do.” The line was quiet, and then: “Do you need anything?”

It was the wrong question and maybe the right one. “No,” I said. “Do you?”

He coughed like he had swallowed a word whole. “No.” And then, “I’m proud of you.”

The compliment clattered in the room like a coin dropped in the wrong machine. I didn’t pick it up. “Take care,” I said, and that was the end of our era for a while.

I went to therapy that summer because healing can be honest and still incomplete. My therapist was a woman named Rhea who wore sensible shoes and asked questions like a person who had read every version of the story and didn’t trust any one narrator, including me. She asked what I needed from a mother and what I learned to give myself instead. She asked what my anger wanted for me. “Not revenge,” I said. “Competence.” She smiled like I’d found a key. “And how will you know you have it?” she asked. “When I can say no without rehearsing,” I said, and by September I could.

I began volunteering on Wednesdays at a community center that offered a free “life admin” clinic for people who needed help with forms and calls and the kind of paperwork that can drown you if you don’t have a boat. I watched a woman cry with relief because someone stayed on hold with the state agency so she didn’t have to. I watched a man learn how to set up online bill pay and buy himself an hour a month to be a person. I brought cookies once, molasses, and watched people eat seconds. On the bus home, a kid asked if I had more, and I did, and I gave him two and a napkin and told him the recipe belonged to my grandmother. His thank you felt like a line that connected us backward and forward.

On our first anniversary, Eli took me back to the bridge where he had proposed and we watched a young couple argue about a map, each convinced they were right. “They’ll figure it out,” Eli said, and I said, “Maybe they both are,” and then we kissed like we were not a solution but a choice.

That night we wrote new vows in the kitchen, simple ones that didn’t require a minister or a witness. I promised to listen when I am tired. He promised to tell the truth first and the explanation second. We promised to leave a light on for each other when we were late. We promised that the phrase forgiveness doesn’t mean access applied to everything outside the line we drew around our marriage. We signed our names at the bottom like a contract no court would ever see and put the paper in a drawer with the spare keys and the list of things I wouldn’t apologize for.

I sometimes think about the girl I was at seventeen, the one who learned to become background noise in her own home. If I could go back and sit beside her at the kitchen table, I would pour her a glass of water and ask how her day was and then listen to the answer. I would tell her: You are not loud. You are clear. There is a difference. I would tell her: The first time you lock a door and it doesn’t scare you, that’s when you have begun. I would tell her: You get to choose which bridges to cross and which to watch from the bank. And in case none of that landed, I would slide a recipe card across the table and say, “Bake these. Feed yourself first.”

In late October, Lantern & Bridge signed a contract with a small bookstore on the east side—the kind of place that still handwrites staff picks and knows which poet you’ll fall for next. The owner, a former librarian named Keisha, wanted a campaign that felt like a neighbor waving from the porch. We spent Saturdays there, rearranging displays, making little videos with a phone and natural light. On the day we launched, a line formed that trailed past the mural of a blue heron and a crown. I watched people carry books to the register like they were carrying themselves home. At closing, Keisha hugged us both and whispered, “You made it easier for people to belong.”

Maybe that’s all I wanted. Not a family that knew the right words in public, not a church that could train a child to perform goodness, not a parent who would apologize in a way that asked to be absolved for free. I wanted a room where the chairs faced the center, a table that expanded because the guests multiplied, a porch light that meant what it said.

One evening, as the early dark began its long occupation of the city, I stood on our balcony with Hawthorne twining himself between my ankles and watched the street below fill with small rituals: a father hoisting a toddler, a cyclist balancing a baguette, neighbors arguing gently about where to hang the holiday lights. For a moment that had nothing to do with Ohio or arguments or cease-and-desists, I felt my life settle into itself like flour into batter. I breathed, and my breath didn’t catch on anything sharp.

A text came from a number I didn’t have saved, an Ohio area code. I looked at it, then at the sky. The message was five words: I hope you are well. I thought about how much can be hidden in five words and how much can be refused. I set the phone facedown on the table and went inside to stir the soup.

Years will pass and this story will reduce itself to the essential ingredients: a girl, a door, a bridge, a light. People will ask whether I forgave my mother and I will say yes, because I did. People will ask whether we reconciled and I will say no, because we didn’t. The difference is the whole point. I will try to explain gently that forgiveness is a coat you wear for your own warmth, and access is a key you give to someone who has earned it.

Before bed, I check the locks. I turn off lights. I lay out the coffee mug I like best. Eli turns off the last lamp and says something small about tomorrow. Hawthorne leaps onto the bed with the entitlement of a creature who has never felt unwelcome. I close my eyes and see, briefly, a picnic blanket in a county park in a town I left and a woman who knew how to arrange a photo but not a family. I watch the scene fade like old film in light. In the space it leaves, I place the image that matters now: a kitchen with a dented tin ceiling, two mugs, rain on the bridge, a quiet I built. I listen to the sound of my own breath and think, again, and again, and again: Love stays.

News

While the entire ballroom was applauding, I saw my mother-in-law quietly drop a “white pill” into my champagne flute — she thought I’d drink it; I swapped the glasses and smiled; she raised hers, the music jolted to a stop, every eye snapped our way — and that was the moment the wedding turned into an unmasking no one saw coming.

At My Wedding Reception, My Mother‑in‑Law Slipped Something in My Champagne—So I Switched Glasses I saw her hand hover over…

“My Dad Works at the Pentagon,” a 10-Year-Old Said. The Class Laughed, the Teacher Smirked—Ten Minutes Later, the Door Opened and the Room Went Silent.

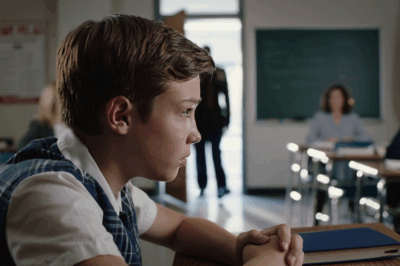

When the bell for morning announcements chimed through the beige halls of Jefferson Elementary, Malik Johnson straightened in his seat…

My dad dragged me across the driveway by my hair for blocking my sister’s car…

My dad dragged me across the driveway by my hair for blocking my sister’s car. The gravel scraped beneath my…

On My 29th Birthday My Parents Ignored Me And Sent My Sister To Hawaii — “She’s The One Who Makes Us Proud.”

The morning I turned twenty-nine, my apartment sounded like a paused song. No kettle hiss, no buzzing phone, no chorus…

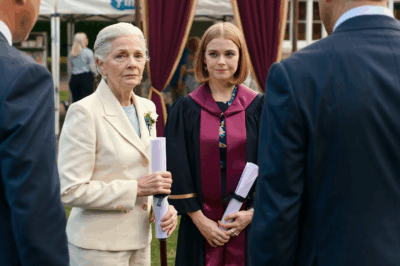

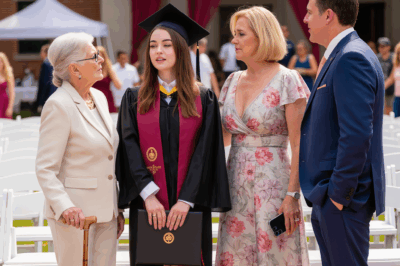

My wealthy grandmother said, “So, how have you spent the three million dollars?” — I froze right there at graduation — and my parents’ answer silenced the entire family…

The graduation ceremony stretched across the manicured lawn like a postcard of American triumph—burgundy and gold banners, folding chairs squared…

Graduation day. Grandma asked one question: “Where is your $3,000,000 trust?” — I froze — Mom went pale, Dad stared at the grass — 48 hours later, the truth evaporated into view…

The graduation ceremony stretched across the manicured lawn like a postcard of American triumph—burgundy and gold banners, folding chairs squared…

End of content

No more pages to load