The Envelope at Graduation

By the time Gregory lifted his champagne flute and announced he was leaving me, the silverware had already paused mid-clink. The private dining room off Broad Street was a study in tasteful celebration—white linen, college pennants framed on brick, a view of the Savannah River turning copper under late-afternoon light. Our daughter’s mortarboard sat slightly askew on her curls. Someone at the end of the table still held a phone up, mid-photo, capturing the moment he should have been toasting Amelia’s summa cum laude and instead declared, without a tremor, “I’ve decided to start a new life without you.”

Fifty faces turned. A chorus of breaths drew in and didn’t quite let go. It would have made good theater—if I hadn’t already staged the ending.

“Congratulations on your honesty,” I said, and I said it like I meant it. I placed the cream envelope beside his charger, the wax neat, the crease perfect, a quiet punctuation mark between us. Then I kissed Amelia’s cheek, wished everyone a lovely afternoon, and walked out. It was not graceful so much as deliberate, a woman stepping out of a role she had overplayed for twenty-eight years.

Augusta heat—real, heavy, old—wrapped me on the sidewalk. Beyond the window glass, cutlery hesitated, whispering resumed, and I heard the door bang behind me with Gregory’s voice already pitched higher than his comfort. “Bianca. What the hell is this? What have you done?”

The envelope was not a love letter or a plea. It was a map and a timer. It was the first motion in a process I had built quietly over months while cooking dinner and paying bills and listening to him describe, with almost moving sincerity, a life that somehow managed to cost more than it paid. If he had looked back at me in those last years, if he had asked my face what I knew, he might have seen the calm of someone who had read the end of the book and was only turning pages to be polite.

I drove home through late-spring light, azaleas bracketing the sidewalks like a parade that had just missed us. Our colonial had the kind of bones realtors wrote copy about: deep front porch, original banister smoothed by the ghosts of careful hands. I turned my key. The house inhaled and then relaxed the way houses do when the person who tends them steps through the door.

Upstairs, in the master closet, two charcoal suitcases waited in the corner—packed, aligned, zipped. His leaving had been hung and folded days ago, pressed and ready. I touched nothing. I poured water into the fern that only liked the light from the west window. I checked a calendar note: 9:05 a.m., Clerk of Superior Court—filed. 10:30 a.m., judge’s clerk—confirmed receipt. 11:45 a.m., email from Philip Anderson, my attorney: Emergency motion stamped. The system is slow until it isn’t; preparation makes it fast.

The first anomaly, months earlier, had been so small that anyone else would have missed it: a debit card charge labeled “Spruce & Harbor” that did not correspond to any table I had eaten at and to which Gregory had never taken clients. I keep ledgers the way other people keep diaries. A quick search revealed Spruce & Harbor was not a restaurant but a boutique hotel two counties over with rooms named after winds. I went colder than the numbers required. Then came a string of transfers, eighty-seven dollars here, three hundred there, always on Thursdays between 4:10 and 4:40 p.m., moved to an account at a bank we had never used. The notes were meaningless: “misc.”, “supplies”, “vendor.” If you have reconciled books for a living, you know the difference between a messy life and a deliberate lie.

I pulled statements, copied them to a folder with an innocuous name, printed hard copies, and slid them into a manila file labeled “Choir Music.” I retrieved our prenuptial agreement from the safe-deposit box at Community First, the one he had insisted upon when his father floated him a stake to launch a software company that lasted one feverish year and a half. I remembered his smile when we signed, the way he said, “This is just to be responsible, Bee.” My family money—grandfather Caldwell’s dry goods turned into distribution centers turned into dividends—required my own lawyer at twenty-six. We had added mutual disclosures, a sunset clause for most covenants, and, at my counsel’s suggestion, a fidelity clause that didn’t expire. Gregory skimmed it. He was already inventing the self he would be by forty.

I did not confront him when I found the hotel photographs in his phone gallery, framed in the way men think is art—her chin tilted into light, the stem of a wineglass reflecting something gold. I did not say a word when I scrolled past a saved Zillow page for a Tybee Island cottage and a text from a number saved as C. that read, “Imagine waking to the water every morning.” I recorded, instead, the conversation he began on a Tuesday where he rehearsed his bravery: “After the graduation I’ll tell her. It’s cleaner in public,” he told Cassandra. “She won’t make a scene.” Cassandra replied with that eager sweetness people wear when they think kindness can make a wrong thing right. “She’ll be okay. She always lands on her feet.” He laughed. “She trusts me. That’s her weakness.” Georgia requires one party to consent to a recording. I have lived here long enough to know the law as well as I know the seasons.

By dinnertime that day, the house smelled like rosemary and paper. I sent Amelia a text at the restaurant that afternoon—Proud of you. This is not your burden. Celebrate. I love you.—and sat in our living room with my laptop closed, hands folded on the cover the way my mother folded her hands over hymnals. Gregory slammed through the door, half fury, half performance.

“You served me divorce papers at our daughter’s graduation,” he said, lips pulled thin. The envelope had been opened. The preliminary filing copied, the exhibits tabbed, the temporary restraining order request on joint accounts in place.

“I filed them this morning,” I said. “You planned to leave tomorrow.”

“The prenup won’t hold,” he snapped, always the fast study in the wrong class. “Any lawyer will tell you the thing expired.”

“Section Twelve never sunsets,” I said. “Infidelity provisions remain until the marriage ends. Section Eighteen clarifies duration as the term of the marriage plus any proceedings resulting from dissolution. You signed, Gregory.”

His color drained in a visible tide. He sat. He stood again. He paced and then did not pace, a man trying to choose between three exits in a hallway with no doors. “This is vicious,” he said finally. “This is not you.”

“I have been me the entire time,” I said. “You simply preferred an earlier draft.”

My phone hummed with Amelia—Where are you?—and Diana—Call me—his sister whose loyalty had always been quiet and firm. I texted Amelia: With Aunt Di tonight. I’m okay. We’ll talk later. She sent back a heart and then three, as if more could stack protection around me.

Diana’s bungalow sat in a street canopied by live oaks, the air under them always cooler by a degree that feels like mercy. She opened her door before I could knock, pulled me in, and pressed a glass of wine into my palm like a benediction. “He did it at the table?” she asked, already furious on my behalf. “In front of our girl?” I nodded. Diana cursed in a whisper and then a louder word she only used when grading plagiarized essays.

“What was in the envelope?” She asked when I had steadied. I told her. I told her about the transfers and the hotel and the cottage and the clause, and she laughed once, a sound with more joy than cruelty. “The prenup,” she said. “God, I remember when he insisted. He thought it meant he was the kind of man who would someday need one.”

Amelia arrived with mascara smudged and shoulders squared. She had always been a Caldwell on the inside and her father’s in the room: pragmatic and incandescent. She hugged me hard and then pulled back, searching my face the way she used to when she was five and checking for fever. “Why didn’t you tell me?” she asked. “I didn’t want to take your last semester from you,” I said. “It wasn’t mine to take.”

We were still in Diana’s yellow living room when the doorbell rang and opened without waiting. Gregory stood on the threshold with Cassandra a pace behind him, her poise slipping, eyes taking in the books and the rugs and the framed photos of other graduations where he had behaved.

“Unfreeze the accounts,” he said before hello. “We can be adults.”

“We will be adults in court in three days,” I said. “Until then, the judge’s order holds.”

Cassandra looked at him, really looked, perhaps for the first time as if facts were not just unfortunate but binding. “You have another account?” she asked when I mentioned it, voice turning a shade cooler. Gregory did not answer. It was a strange relief to watch the theater close for someone else.

“Please leave,” Diana said finally, stepping into the space between us and the past. “My niece has been celebrated, my sister-in-law has been humiliated and triumphed, and I am out of wine.”

The hearing was held in a courtroom with ceilings too high for melodrama. The judge wore her hair in a silver coil and her patience in thin layers. She read the agreement as if it were literature and not a weapon. She read the bank statements as if they were weather, changeable but not unknowable. “Section Twelve remains in effect,” she said, and did not look at Gregory, who stared at the table as if it might produce a loophole. She granted the freeze with exceptions for necessities. She affirmed my possession of the house pending dissolution. Gregory’s attorney, a young man with good shoes and the wrong specialty, murmured objections like apologies.

We left with the law around us like a fence we had chosen together decades earlier and he had assumed would rot. Outside, rain steamed on pavement. Gregory caught my elbow. “Twenty-eight years,” he said. “Doesn’t that count for anything?”

“It counted for everything,” I said. “Until you decided it didn’t.”

People like to say news travels. In Augusta, it floats. Word of what happened at Broad Street curled around church pews and coffee counters and the back row of yoga, where women with ponytails plucked conclusions like threads. Some called to bring casseroles and sit. Some called to ask questions that sounded like concern and were not. “We’re all so shocked,” one friend said brightly, a tremor under her brightness. “But were we?” another friend said gently, because truth often arrives by the softest voice.

Gregory’s life, curated like a magazine spread, began to show its seams. The beachfront cottage went back on the market. The deposit on the car labeled “aspirational” was returned. Cassandra, who had stepped from the world of acquaintances into the world of consequence, moved out of the apartment she thought they had rented together. She told a mutual friend she had not signed up to play accountant. I did not gloat. I went to work.

The office I leased downtown had once been a travel agency, its walls still faintly marked by maps. I painted them a forgiving white, set a ficus by the window that would either live or not depending on its own will, and hung a brass plaque that read CALDWELL FINANCIAL TRANSITIONS. I bought two armchairs that did not match but spoke to each other and a long table that wanted to be filled with paper. My first clients were two teachers who had married each other young and were now unknitting that mistake, another a nurse whose husband had died with three hidden credit cards and one boat. We talked about APR and beneficiary designations and what it costs to stay and to go. I watched women’s shoulders drop when they understood a spreadsheet, when numbers that had been shame turned to options. It was visceral—this work of translating fear into a plan.

On the way home some evenings, I drove past the river where runners traced the edge of water and families posed for pictures in front of a history they did not have to know to enjoy. I thought about Charleston and our tenth anniversary when Gregory had remembered to be good, about two miscarriages before Amelia and the way grief sits in a body like a foreign coin you keep finding in your pocket. I did not revise the past; I allowed it to finally hold the weight it deserved and no more.

Amelia called from Charleston, where she had taken a job and an apartment with a window that looked onto a courtyard with a magnolia that would bloom whether she watched it or not. “My boss is a tyrant in a good way,” she said. “You’d like her. She doesn’t apologize for being excellent.” We talked like adults who had also been mother and child, our sentences braided with the knowledge that love can be sturdy even when the shape of family changes.

Gregory texted once to say Cassandra had left. He texted again to say he was sorry. He called to say he was drowning. I did not answer the first two and returned the third with the name of a therapist and a list of financial coaches who were not me. Our boundaries were not cruel; they were architecture.

The final hearing fell on the date that used to be our anniversary; the coincidence landed with the satisfying click of a book’s last page sliding into place. Gregory looked smaller in the courtroom, not thinner but less certain where to put his limbs. The judge upheld every clause. The house and the bulk of retirement and the investment accounts accrued under my steady hand remained with me. He left with what the agreement promised: his separate account, his personal property, and the reality of his choices.

In the hallway, he waited. “I made a terrible mistake,” he said, not reflexively, but as if the words might be the first honest thing he had put into the air in months.

“You did,” I said. “And now we both live with it.”

He nodded. “I hope you find happiness, Bianca. You deserve it.” He meant it. It is a strange kindness when someone who has broken your life offers you a benediction you no longer need.

Six months later, the ficus had decided to live. I had hired two associates, women who knew numbers the way musicians know scales. We hosted free Saturday clinics for anyone who came through the door, coffee brewing in a machine I learned to descale, pastries donated by a baker who liked our mission and our receipts. We taught seventeen women in one morning how to pull their credit reports and read them without flinching. One of them—Lydia, from the nurse’s boat—brought her daughter by to say thank you. The girl was fourteen and sullen and beautiful, the way girls are when they do not yet understand how rare time is. “She thinks I’m a hero,” Lydia said, embarrassed and proud. “She’s right,” I said.

At home, I changed the air filter and the porch light and learned the precise angle to coax the storm window into behaving. I kept the grandfather clock wound and set five minutes fast because it felt like optimism. Some evenings I set the good china on the table just for me and ate the food I wanted slowly, forks placed down between bites like punctuation. The house felt like a skin I had returned to after years of being too cold or too warm. The fern forgave me when I forgot its water.

There were nights I cried, and they were not wasted. There were mornings I missed the outline of another person in the world and then remembered that outlines are not always shelter. Diana taught a seminar on Southern Gothic that semester and left photocopied pages on my desk of Flannery O’Connor and Eudora Welty with sentences underlined not for their meaning but their sound. “You have always been a woman of good sentences,” she said. “Now you have time to hear them.”

What remained of my marriage became a story I could tell myself without flinching. We had been young and hopeful and sometimes kind. We had been selfish and careless and sometimes cruel. We had made a beautiful person together and watched her step into a life with grace I could not have found at her age. We had been ordinary and special like most long things.

When Amelia came home for Thanksgiving, she stood on the porch and looked at the door trim and said, “I didn’t know the house could feel like this.” We walked to the river in sweaters and watched a boy catch nothing and feel victorious about it. We cooked too much and threw almost nothing away because I had been a mother long enough to turn leftovers into a second act. On Sunday, she pressed a kiss to my cheek and then to the doorframe the way she used to when she was little and superstitious, then drove back to her magnolia and her tyrant who, by then, felt like a mentor.

Gregory married no one. He tried sobriety and then tried again. He shut down a business that would have died without him and began consulting for a company where his voice did not have to lead. He sent Amelia birthday gifts on time. He sent me an email once, years later, with a single sentence: Thank you for not burning the whole thing down. I did not respond. I did not need to. Not all closure requires applause.

In December of the second year, I hung a wreath made of magnolia leaves and laurel and placed a small bell near the bottom where only those who looked closely could see it. When the door opened, the bell rang softly, the way memory does when it chooses to be gentle. Women walked through that door carrying folders and shame, hope and receipts. They left with plans.

On a Sunday evening, I sat at my kitchen table with a stack of pro bono files and a slice of pecan pie and thought of the envelope, of wax and crease and the weight of paper when it changes a life. I had been practical for so long I’d almost forgotten that practicality could be an instrument of mercy. A prenup is not romance. A ledger is not poetry. But the work of keeping yourself whole is a kind of love song.

When I picture that afternoon at Broad Street now, I can see the exact way the light hit the champagne and turned it something that looked like courage in a glass. I can hear the collective silence, the way it bent toward noise and then did not break until I stood. I can feel Amelia’s cheek against my lips, warm and startled and strong. The door closed behind me and opened again on a life I had built in parallel without quite admitting it.

There is a river in this town that keeps moving whether or not you name it. I learned to step into the current and let it carry me forward, not away. And when I look back, I do not see a woman abandoned. I see someone who handed a man an envelope and took, at last, her own hand.

The truth is not that my husband left me. The truth is that I chose the truth, and the truth, in returning the favor, gave me back everything I thought I had lost—and then added a room with better light, an office with a ficus, a daughter who trusts me, a sister-in-law who is a sister, and a house that is finally, fully, mine.

I do not keep the envelope. It served its purpose and then became paper again. But sometimes when I am leaving the office late and locking the brass-handled door, I imagine sealing something invisible for the women who will come tomorrow. I imagine tucking it beside their plates—here is the map, here is the timer, here is the permission to stand up and walk outside without hurrying, to let the air meet you like an old friend, to know that even if someone follows you into the heat yelling your name, the story is already yours.

And it is enough.

Enough, I’ve learned, is generous. It rarely stays the size you think it will. It swells to hold what comes next—the quiet, the loud, the work, the rest. After the clinics on Saturdays, when the last woman leaves with a folder fat with copies and a list of phone numbers, I sweep the lobby myself. It’s not frugality. It’s ritual. Paper clips collect in the dustpan like shed punctuation. The glass door shows my reflection not as a caution but as a fact: a woman who did not go up in smoke when the script changed.

On a Tuesday that started with rain and ended with that early-spring glare peculiar to Georgia, a woman named Connie walked in wearing a cardigan buttoned wrong by one. She used to be a bookkeeper for a drywall outfit, she said, until the owner’s son took over and declared spreadsheets “old school.” She slid me a stack of statements as if they might sting. Her husband—ex-husband, she corrected, the word holding somewhere between her teeth and her ribs—had run their credit into the ground in the year between his first affair and the second. “I can’t hear numbers without hearing him,” she admitted. We laid her debts out on the table in order of interest rate and shame. Shame goes last. It’s the only way to finish.

I told Connie what I tell everyone: There is no moral category called hopeless. There are balances and due dates and settlements and plans. We stitched one together. Three months later she brought me a lemon pound cake that didn’t need frosting and a photo of her standing on the front steps of a two-bedroom duplex with a porch deep enough for a chair and a plant. “I sleep through the night,” she said. Her cardigan was buttoned right.

On Thursdays, Diana and I eat together at a diner where the waitress calls everyone honey without irony. We split a Cobb salad and something fried because equilibrium is a practice. She reads me student sentences that try too hard and the occasional line that shivers the room. I tell her about a client who cried not because she was afraid but because she realized she wasn’t anymore. We toast with sweet tea, and the ice clinks like luck.

Sometimes the past doesn’t knock. It sits at the counter two stools over reading the sports page. Once, months after the decree was final, I saw Gregory at the hardware store considering lightbulbs with the seriousness he once reserved for a pitch deck. He saw me, too. For a moment, the aisle hummed with what-ifs and why-nots and goodbyes we had both already said. “The soft white makes dining rooms kinder,” I said, because it was true. He nodded, then looked at the shelf again as if the right answer might turn toward him. I paid for my paint and left. In the parking lot, a woman stopped me and whispered, “You don’t know me, but I was in the restaurant that day. I think about the way you stood.” I wanted to tell her I had sat more than I had stood, that most courage happens at tables with pens. I just said thank you and meant it.

Amelia’s life took on a shape that belonged to her and not to the story of us. She learned the trick of bringing a boss better questions than problems. She dated someone who collected vinyl and arguments, then someone who built furniture and only sometimes finished it, then someone who understood the language of deadlines the way scuba divers understand breath. “I’m trying to learn what I want without rehearsing what I’m willing to tolerate,” she said. I told her that was a sentence worth writing on an index card and keeping in a drawer.

She came home one weekend with a plan to repaint her old room. “Not because I’m moving back,” she said, rolling her eyes preemptively at a joke I hadn’t made, “but because every time I open that door I see the same poster I stuck up at sixteen and the same nail holes. I want you to see something that looks like now.” We picked a color the paint swatch called sea glass, which is the industry’s way of admitting that what they want to say is memory. We moved the desk under the window. We took down a string of twinkle lights that had burned out in 2015 and kept hanging like a lie. We kept the bookshelf and the uneven heart she carved with a compass on the closet’s inside edge. We stepped back, and for a minute neither of us spoke. “It looks like a room that believes me when I say I’m okay,” she said. That night, she slept there anyway, not because she needed to, but because wanting is its own good reason.

A year out from the envelope, I started a Wednesday-evening series at the office called The Numbers You Live With. We filled chairs in a half-circle and talked credit utilization like we were discussing recipes. We practiced calling the bank and asking for better terms the way you practice a speech: polite, specific, persistent. Once, after a session on negotiating raises, a woman named Bree stood in the doorway and asked, “But what if they say no?” I told her the truth: that sometimes no means not now and sometimes it means go. “Which is worse?” she asked. “Usually not now,” I said, “because it teaches you to shrink in place.” She came back two months later with a story about a new job and a salary that recognized the hours she had already been giving.

In those chairs, the word divorce came up less than you’d think. What came up more were mothers who had raised children alone and then discovered they did not know how to stop bracing, widows who had paid for funerals in cash and groceries with change, daughters who had become guardians without fanfare. Men came, too—quiet, often, or loud in the way fear is loud. We did not turn them away. Money is a language, and fluency should not depend on luck.

Cassandra wrote to me. The email arrived at 2:11 a.m., which is when confessions knock. She apologized—not in a way that expected anything back, but in a way that suggested she had stayed up trying on the sentence until it fit. She said she believed Gregory when he said I was cruel and calculated, and she believed me when I said I wasn’t. Both had been convenient at different times. She said she found herself standing in front of a jewelry store window unable to remember which bracelet had made her cry and which had made her sure and realized maybe the problem was that she’d asked bracelets to do either. She hoped I was well. I did not reply. The impulse to absolve is strong in women who have been raised to keep everyone fed. I set the email in a folder called Completed. I wished her a kinder story in my head and went to bed.

There was a man who fixed our office door when it began to stick. He introduced himself as Joe Larkin and wore the name like it had been through the wash enough times to soften. He was tall in the way doorways notice. He measured twice and cut once and apologized to the floor when he dropped a screw. He told me he had a daughter my age and a wife who taught kindergarten until she didn’t. He didn’t say the word widow and didn’t have to. We drank coffee in paper cups while the new hinge remembered how to be a hinge. He told me the best kind of leveled door is one you don’t notice at all. I told him the best kind of budget is the same. He smiled in a way that made my kitchen feel different that night, not lonelier or fuller, just honest. We didn’t rush it. We let the hinge learn.

Once, Amelia invited me to Charleston to watch a movie projected on a wall in a courtyard. Strangers sat on blankets and let the night fill the parts of them the day had emptied. Halfway through, the film flickered and froze, a single frame suspended above us like a held breath. People laughed, then groaned, then quieted while a person who knew what to do did it. The projector hummed. The picture returned. The crowd clapped, an applause aimed at recovery rather than art. “That’s what the last two years have felt like,” Amelia said, resting her head on my shoulder for the length of a scene. “Pause. Hum. Continue.”

Gregory went to meetings that gave him coins and slogans. He took up walking, the pedestrian version of fleeing. He texted Amelia enough to be a father and not so much that he became a weight. Once, he sent me a message that read simply: Thank you for not telling everyone how bad it was. I wanted to say it wasn’t my story to tell. I settled for You’re welcome because sometimes courtesy is the cleanest line between two people who used to share a house.

The house, meanwhile, remembered me. I replaced the dining room fixture with one that threw light not just down but out. I planted herbs in a window box and threw out the dill when it grew arrogant and bitter. I learned the precise, unlikely angle the backdoor needs in August when the wood swells like a boast. Diana fixed a leaky faucet with a wrench and a curse. We discovered we could move the sofa three inches to the left and both feel calmer. None of it was magic. All of it was home.

My parents visited and pretended not to take inventory the way parents do when they are proud and a little scared that their child has grown past the end of what they had pictured. My mother ran a fingertip over the edge of the mantel and said, “It feels like the same house you’ve always had, but the echo is gone.” My father tightened a faceplate and pretended I couldn’t see him do it.

In the second spring, the azaleas out front lost their minds, pink like a dare. I hosted a small party at the office to mark two years of doors opening and numbers settling. We set out deviled eggs and cheese straws and lemonade that required no improvements. Women came wearing the newcomers’ look of half-defiance, half-hope. I said a few words that sounded like me because I had written them as if I were forgiving myself for once thinking I needed permission. Diana read a toast from Eudora Welty about knowing when you’re in your place. Joe fixed a wobbly chair and stayed for a cookie. After, when we were stacking plates in the tiny sink to wash tomorrow, a woman I barely knew squeezed my hand and said, “You know, the thing I tell my sister is that you didn’t just leave a man; you left a system.” I didn’t correct her because she wasn’t wrong. Systems are made of people and paper, of habits and expectations. I had unlearned several and kept a few. Both were work.

If there was a day I knew I had built something that would outlast these years, it was a Tuesday in late October when a fourteen-year-old came in with her mother. She sat straight-backed and sullen and determined not to be a child in a room where money was discussed. She used her phone as a shield and then put it down without being told. Her mother asked careful questions and then one that wasn’t careful at all: “How do I teach her to be the kind of woman who never has to walk into an office like this for the reasons I did?” I told the truth. “By letting her hear you ask every question you’re scared to ask and then letting her watch you answer them. By letting her see receipts and budgets and bank apps. By letting her watch you look at a number and not flinch.” The girl’s shoulders dropped. She asked how credit scores work and I told her with a diagram on a sticky note we stuck on the back of her phone. She smiled and pretended not to.

At Christmas, Amelia and I drove to the coast and rented a cottage that smelled faintly of salt and board games. We walked the beach at low tide and found a shell so intact it felt staged. We made spaghetti and ate it out of bowls in our laps, which is the appropriate way to eat it when you are happy and unobserved. We talked about the year ahead as if it were a pantry we were filling thoughtfully. On the second day, in a store that sells the same Christmas ornaments every town insists are unique, we found a ceramic envelope. We laughed because the universe occasionally takes up comedy. We didn’t buy it. We didn’t need the reminder.

I heard from Cassandra again once, not to apologize this time but to ask a question that surprised me by being the one I had asked myself for years and had only recently stopped needing answered. “How did you know when you were done being angry?” she wrote. I didn’t have a clean answer, only this: “When being angry started to feel like a way to stay near him.” I clicked send and hoped she felt something unclench. I closed the laptop and went out to the yard to check on the basil.

The basil had bolted, which is what happens when the plant forgets its first purpose. I trimmed it back ruthlessly, which is mercy in that language. I think of all the trimming back that has saved my life: the cutting of expectations that no longer fed anything, the pruning of conversations that grew in circles, the shearing of the need to be understood by people who preferred me small. The plant recovered. Most things do when you remove the parts that are trying too hard.

A letter arrived from Gregory during the third summer. He had started an intensive program for people whose addictions are nouns and verbs. He wrote with bluntness I recognized from the way he used to pack a suitcase: I did things I cannot believe I did. He apologized for the restaurant. He apologized for the money. He did not ask for anything. I read it at the kitchen table and cried the way you cry when the train you didn’t know you were listening for finally passes in the distance. I put the letter in a drawer. Not the one with warranties and receipts. The one with birthday candles and string. The drawer where you keep objects that are not practical but feel useful anyway.

I have not fallen in love again, at least not in the way that makes you forget where you put your keys. I have fallen in steady with my days. Joe and I eat breakfast on the back steps sometimes—coffee for me, tea for him, toast we butter to the edge because we are not puritans. We talk about hinges and budgets and grandchildren not yet born. We form the beginning of a habit and refuse to hurry it. I do not need a ending to make the middle beautiful. That lesson took fifty-four years and a well-sealed envelope.

When Amelia got engaged—standing in a marsh at dusk, a ring that looked like light itself, a man whose freckles made him look perpetually summered—Gregory called me before he called her. “I want to do this right,” he said. “Tell me what doing it right looks like.” I told him it looked like showing up early and staying late, like not making speeches and making sure the florist is paid on time, like asking our daughter what she wants and believing her answer. He said, “Okay.” He did. At the rehearsal dinner, he raised a glass and said one good sentence about our girl and not one about himself. I saw Cassandra in the back of the room with someone kind-looking whose hand knew how to hold hers. We nodded at each other, something like forgiveness traveling the length of air between us without either of us having to carry it.

On the morning of the wedding, I stood alone in the kitchen with my palm on the cool countertop and let myself feel the past like weather. Then I drove to the venue and found Amelia in a robe and bright socks, exactly herself. I zipped her dress. I dabbed at her lipstick with a tissue the way my mother did for me. I told her the number we never said out loud: the cost of a life well loved is never the ledger’s sum. It is always, somehow, more and less. We walked to the place where she would say a vow and stood at the edge a moment to listen to the river that was not the Savannah but might as well have been. Water is water. It goes on.

When it came time for the parents’ dance, the DJ called my name and Gregory’s, and we stood up together because that’s what you do when one story ends and another begins in the same room. We did not step on each other’s feet. We did not speak. We held a polite distance and looked at the woman we had made who was promising to build a house with somebody else. My eyes got wet, which is not the same as crying. His did, too. The song ended. The room clapped. We let go.

I went home that night to a clean sink and a note from Joe propped against the sugar bowl: I fed the fern. It looks smug. I laughed, alone, out loud. I took off my shoes in the hallway and felt the floor forgive me for the years I ran across it carrying more than I could hold.

Sometimes, after closing the office, I walk down to the river and sit on a bench that knows me. I watch the water do what it has always done, bringing things and taking them. I think about the women whose folders line my shelves and the ones who never needed me because somebody taught them early and well. I think about the envelope, which was not a threat or a weapon or even a symbol. It was a piece of paper holding a fact. I think about the way facts, when finally named, make room for joy.

If you are reading this because you have stood where I stood—with strangers watching and your husband choosing to perform the leaving—know this: the theater ends. The kitchen remains. The work of your hands will bring you back to yourself. So will your ledger, your porch, your sister’s good cursing, your daughter’s sea-glass room, your ficus that lives because you kept showing up with water even when it was indifferent. One day you will buy soft white bulbs without apology and learn again how your face looks under kinder light.

And if there is ever again an envelope in your hand—sealed, heavy with what it carries—may it be a letter to yourself. May it say: Here is the map. Here is the timer. Here is the door. Open it. Step into the heat. Let him yell if he must. Keep walking until the voice you hear is yours.

News

While the entire ballroom was applauding, I saw my mother-in-law quietly drop a “white pill” into my champagne flute — she thought I’d drink it; I swapped the glasses and smiled; she raised hers, the music jolted to a stop, every eye snapped our way — and that was the moment the wedding turned into an unmasking no one saw coming.

At My Wedding Reception, My Mother‑in‑Law Slipped Something in My Champagne—So I Switched Glasses I saw her hand hover over…

“My Dad Works at the Pentagon,” a 10-Year-Old Said. The Class Laughed, the Teacher Smirked—Ten Minutes Later, the Door Opened and the Room Went Silent.

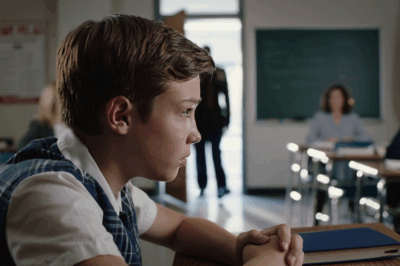

When the bell for morning announcements chimed through the beige halls of Jefferson Elementary, Malik Johnson straightened in his seat…

My dad dragged me across the driveway by my hair for blocking my sister’s car…

My dad dragged me across the driveway by my hair for blocking my sister’s car. The gravel scraped beneath my…

END OF IT ALL – I was told over and over again that I was not welcome at any family events. My mother yelled that events were for real family only.. So when I got married I didn’t invite them and they went crazy asking to fix things but I called such a call

I was taught early that belonging had rules nobody bothered to write down. You learned them by touch: a hand…

On My 29th Birthday My Parents Ignored Me And Sent My Sister To Hawaii — “She’s The One Who Makes Us Proud.”

The morning I turned twenty-nine, my apartment sounded like a paused song. No kettle hiss, no buzzing phone, no chorus…

My wealthy grandmother said, “So, how have you spent the three million dollars?” — I froze right there at graduation — and my parents’ answer silenced the entire family…

The graduation ceremony stretched across the manicured lawn like a postcard of American triumph—burgundy and gold banners, folding chairs squared…

End of content

No more pages to load