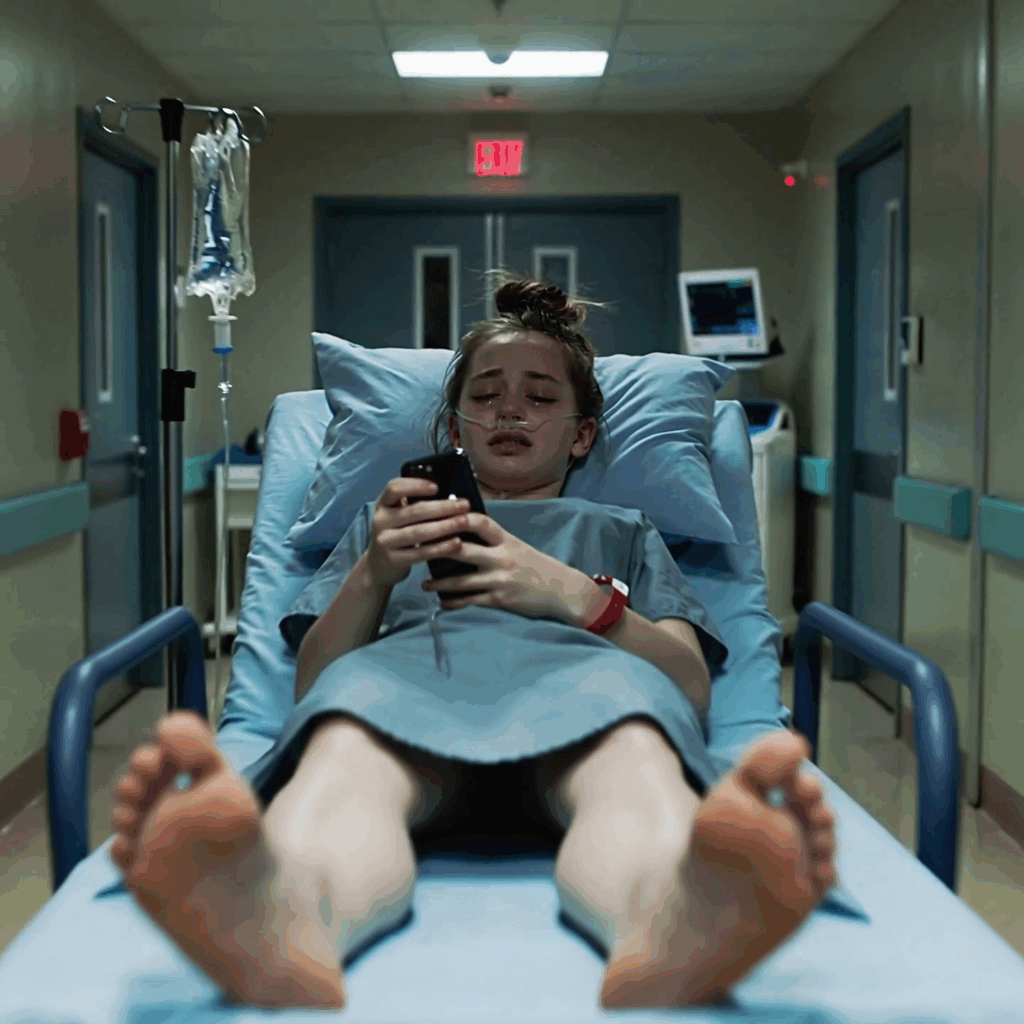

It was Christmas Eve, and Las Vegas was doing what Las Vegas does—glittering like it had never known a quiet night. Inside the Las Vegas Medical Center, the lights were too bright and the room too white, and the only glitter came from a tinsel garland someone had taped to a nurses’ station two doors down. In the corner of my room, my two‑year‑old twins, Ethan and Emily, stacked foam blocks Valerie had found in Pediatrics, their little voices a soft counterpoint to the measured beeping that insisted I keep breathing. My phone—balanced on the blue blanket across my lap—was still vibrating when my mother’s voice cut through the room like a thrown bottle.

“Don’t you dare ask us to cancel our plans again. We’ve had these Elton John tickets for months,” she yelled, her words ricocheting off the video call like they could rattle the rails of my bed. Her face filled the screen: hair perfect, lipstick perfect, the background a resort room with a view of the Strip so glittering it looked like an open jewelry box. Beside her, my father crossed his arms. I could almost smell his aftershave through the glass.

My abdomen cramped with a pain that felt like someone was wringing a towel inside me. When I’d first come into the ER that afternoon—dizzy, clammy, convinced the world had tilted ten degrees to the left—they’d found internal bleeding. It wasn’t slow, the surgeon said, and it wasn’t going to wait for me to finish sorting child care.

“Mom,” I said, but my voice came out thinner than I intended. “I’m going into surgery. I can’t bring the twins into the operating room.”

“You’re always making everything a crisis, Natasha,” my father said, leaning in like the camera owed him compliance. “We’re retired. We deserve to enjoy our lives without your constant problems.”

Retired three years early, I thought. Retired on a “bridge plan” that had somehow become my bank account. Retired the way people retire when their daughter deposits $2,500 on the first of every month because that’s what family does. Even after my husband died six months ago, I kept the transfers. It was the one piece of stability I could keep, the one thing I could press into the gap James left, as if responsibility could be mortar.

On the other side of the bed, Valerie, the night nurse with peppermint scrub pants and a voice like warm tea, adjusted the IV line and squeezed my shoulder with the practiced grace of someone who had made a career of small mercies. “My friend Olivia is a professional nanny,” she murmured. “Trauma‑trained. I can call her.”

My mother sighed dramatically. “Don’t drag strangers into this. You’re overreacting.”

Emily looked up from her blocks and grinned at the shape of her own hand in the fluorescent light, proud of the little shadow puppet only she could see. Ethan pressed a blue cube into the crook of my knee, his solemn eyes requesting approval.

“Mom,” I said, steadier now, “I am bleeding internally.” The words felt obscene, like they were too private to say to people who had chosen Elton John over their only grandchildren. “Please.”

“We have plans,” my mother said. “We haven’t been to a real concert in years. Why do you do this to us?”

The question struck me in a place the painkillers couldn’t reach. I had been an afterthought my entire life—Jessica, my younger sister, the golden child; me, the reliable one who handled logistics and put out fires and wrote checks. I had held on to the idea that my steadiness was love. That love would return. That the pendulum would swing, if not toward my needs, at least toward my children’s.

Valerie leaned toward my screen. “This is a hospital,” she said politely, like she was explaining a library to a toddler. “She’s headed to the OR.”

My father rolled his eyes. “You’re becoming a real nuisance and a burden, Natasha.”

A burden. The word flashed hot and red across my vision. James—who used to call my shoulders “the hinge of the house”—had been gone for six months because a stranger had a second bourbon and a third and slid through a red light like it was his birthright. I had dragged my body through days that felt like wet wool. I had tried not to drown my grief in the arithmetic of bills and daycare and grief group Tuesdays that smelled like coffee and Lysol. And now, bleeding, I was a burden.

“Please end the call,” Valerie said, and I did. The room hummed with the kind of quiet that is not silence: monitors, distant wheels on tile, my kids muttering their private languages. I stared at the blank black screen until my face emerged—a pale oval, hair scraped into a bun, eyes too wide. Twenty‑seven missed calls would come later. For now there was only this choice to make.

“Call her,” I told Valerie. “Call Olivia.”

She nodded, and the decision—so small and so enormous—settled into the space behind my ribs like a stone that finally understands the bottom of a pond.

While Valerie stepped into the hall, I thought of the calendar alert set for the 28th, the one that chirped cheerfully every month: Transfer parents’ support. Mortgage/help. I had told myself it was duty. I had told myself it was love. Maybe it was neither. Maybe it was a leash I had braided from habit and fear and the fantasy of being chosen one day if I was good enough and generous enough and quiet enough.

Valerie came back with a soft knock. “She’s on her way,” she said. “Half an hour, tops.”

“Thank you,” I whispered, because thanking strangers felt clean in a way that thanking my parents never had. “Could you bring me my phone?”

With shaking hands, I opened my banking app. The interface was so cheerful it made my throat ache: little balloons to mark “milestones,” confetti when you hit a savings streak. I canceled the recurring transfer. The screen asked if I was sure. I was so sure I surprised myself. Then I opened a message thread titled Family ❤️ and typed, “I will no longer be providing financial support. My children and I deserve better than being your afterthoughts. Do not contact me again.” My thumb hovered over the send arrow, the way a person hovers at the top of the high dive. Then I pressed.

Freedom, I thought, and immediately felt ridiculous. You can’t call it freedom when you’re attached to an ECG monitor. And yet something inside me unlatched, a small door I had not known was bolted. I let my head sink into the pillow and listened to the fifth‑floor air vent whisper to itself, the building as alive and particular as a person.

Olivia arrived like a promise kept. She was a compact woman in her mid‑thirties with a navy sweater and a messenger bag that looked like it had seen continents. The twins took to her the way thirsty people take to a glass of water—uncomplicated and complete. She got down to their level so fast I thought she might have teleported. She showed Ethan how to make a tunnel out of the blanket, coaxed a laugh out of Emily with a squeaky giraffe, kept one eye on me, and made the whole thing look inevitable.

“Hi, Natasha,” she said, standing and offering her hand like we were meeting at a park instead of fluorescent purgatory. “Val says you’re going to the OR. I’ve got them.”

“Thank you,” I said, because there are only so many ways to say the only thing that matters.

The orderly arrived with the bed like a boat. Valerie rotated my IV pole. Someone pressed a consent form under my pen. The pen shook. I thought of James—his laugh, the way his palm would span my knee when we were driving out to Red Rock Canyon, the way he tied his shoes like it was a craft. “We’ll build our own family,” he used to say when my parents forgot my birthday or remembered it with a forwarded e‑card. “One that knows how to love.”

The last thing I saw before the ceiling tiles started moving was Olivia, kneeling between my kids, pointing out the shape of a reindeer in the tinsel looped over the nurses’ desk. Ethan’s mouth made a perfect O. Emily clapped. The lights above me blurred. Someone said, “Deep breaths.” I did. Then I let the world go slack.

The morphine dreams were stitched with James. He was everywhere—sitting on the edge of a motel pool in Barstow, the sun turning his forearms into a field of wheat; standing in the aisle of a hardware store, frowning at a wall of screws like he was considering each one for adoption; swaying with a drowsy Emily in the doorway, his chin tipped to her hair. In one, he was at the end of a long hall lined with doors. He put his hand on the right one and looked back at me. “This one,” he said, like he had any say in the matter. “It leads to better.”

I woke grafted to the pain. I woke to Olivia’s voice reading Brown Bear, Brown Bear like a benediction. I woke to Valerie’s peppermint pants and the way she snuck me an extra Jell‑O because the sodium would be fine. I woke to beeping and the nursing assistant’s ringtone and the hush‑hush kindness of a tech who brought a mini tree because the shift manager was a softie. I woke to my phone lighting up with twenty‑seven missed calls and thirteen text messages, each one like a tiny gnat hitting a porch light.

Most were from my parents. Confusion first—“What is this about money, Natasha?”—then anger—“You’re being vindictive.”—then logistics disguised as emotion—“The mortgage is due.” My father, economical as ever: “You can’t just cut us off. The cruise is non‑refundable.”

Jessica’s texts felt like they came from another climate. “Mom and Dad said you were being dramatic about a routine checkup. What’s going on?” When I told her the truth, I watched the typing bubbles pop and pause and reappear, the ballet of someone rethinking who raised them. “Oh my God,” she wrote. “I would have watched the twins. I had no idea.”

I believed her. Jessica could be self‑involved the way the golden child often is—not cruel, just practiced at being the axis. But cruelty had never been hers. It had been…environmental.

When I was lucid enough to sign more forms and drink chicken broth that tasted like good intentions, I hired Olivia part‑time. I called a lawyer and drafted a will that named a trusted friend as guardian should the worst happen. I blocked my parents’ numbers and kept Jessica’s because life is not a courtroom; it is a house with many doors, and some of them deserve to stay unlocked.

The days flowed the way hospital days do—thick, fluorescent, punctuated by vitals and visits and the quiet aching gratitude of being allowed to keep breathing. On day five, they let me go home with a sheaf of instructions and a pain management plan that sounded like a truce: rest, hydrate, call if the red flags wave. Olivia drove; the twins slept; Las Vegas lay out the window like a joke someone told to the desert and the desert, inexplicably, laughed.

My apartment looked like a person had tried to clean it and then remembered grief. Dishes drying on a rack that had become a permanent installation. A calendar with six months X’d off in a row and the seventh abandoned. On the fridge, a magnet in the shape of the Hoover Dam. Next to it, a photo of James holding both babies in the hospital, his face dumb with happiness.

Olivia tucked the twins into their room and straightened their small lives the way a careful hand smooths a sheet. “I’ll be here at eight tomorrow morning,” she said. “We’ll do pancakes. You’re going to rest.”

I nodded. It felt like admitting to something I had avoided my whole life: that I deserved care not as a function of usefulness but because I was living and thus eligible for tenderness.

When I checked my phone that night, the message from my father was waiting like a tax bill: “We’ve planned a cruise next month. The tickets are non‑refundable.”

I didn’t respond. I put the phone face down on the nightstand and stared at the ceiling fan until its blades blurred into a white disc, as if the room had its own moon.

Two weeks later, my incision still burned if I moved too fast, but I could stand long enough to make coffee. Work—graphic design for small businesses and nonprofits—bent around recovery, then wrapped around the twins like a useful blanket. My clients were kinder than I expected, perhaps because the people who keep small enterprises alive understand both fragility and grit.

Jessica came by with a Tupperware army of soups and stews she admitted she’d ordered from a meal prep service. “I put them in real containers so it would look like I cooked,” she confessed, sitting cross‑legged on my rug while Ethan offered her a plastic spoon. “Don’t out me.”

We talked like women crossing a river on steppingstones—careful, choosing each step, both pretending we didn’t notice when the water licked our ankles. She told me how Mom and Dad framed my surgery as “one of Natasha’s phases,” a thing to be endured like a weather pattern. “I believed them,” she admitted. “I’m sorry.”

I laughed once, the sound sharp in my throat. “That’s the thing about believing people,” I said. “It’s not a crime. Sometimes it’s a kindness. You just have to decide when to stop.”

A week after that, the knock I had been expecting landed on my door like a gavel. Through the peephole, my parents looked smaller than I remembered them and somehow louder. My mother clutched her designer purse like a life preserver; my father held his arms stiffly at his sides, the way he does when he wants the room to remember he is the authority.

I opened the door four inches. “What do you want?” I said, surprised at the evenness of my voice.

“Natasha,” my mother trilled, her tone sugared. “We’ve been so worried. You haven’t answered our calls.”

“We need to discuss this ridiculous financial situation,” my father interrupted, pushing against the door with his presence. “The bank called. We had to dip into our cruise savings to cover the mortgage.”

I let the silence spread out between us like a rug. “I told you I’m cutting financial ties,” I said finally. “I meant it.”

My mother’s lips trembled in what I had once mistaken for empathy. “We’ve come to depend on that money. We adjusted our lifestyle based on your commitment to help us.”

“‘My commitment,’” I repeated. The words tasted like something I would no longer eat. “I sent money out of guilt and obligation while you couldn’t watch your grandchildren during my emergency surgery.”

“That’s not fair,” my father said. “We had plans.”

“More important than my life?” I asked. “Than your grandchildren’s safety?” I watched their faces. They were not cruel people by their own lights; they were simply people who had prioritized themselves so loudly that no other song could be heard.

As if on cue, Emily toddled into view with her stuffed giraffe dragging its satin tail. My mother bent toward her, voice high and bright. “There’s my precious grandbaby,” she cooed.

Emily backed up until she hit my shins and then wrapped her arms around my leg, her small body making a statement larger bodies had failed to make.

“I think you should leave,” I said quietly. “If I’m ever ready to talk, I’ll reach out.”

My father opened his mouth. “The money—”

“—is no longer your concern,” I finished. I closed the door gently. I leaned my forearm against the wood. My heart thudded, a bass drum I had neither invited nor tuned. On the other side, I heard my mother’s voice rise and fall, Aunt Patty’s name, the word reasonable wielded like a baton.

The following afternoon, my extended family inbox pinged with a message from my father to everyone within two degrees of kinship. Subject: Concern. It read like a deposition written by a playwright who had learned sentiment by rote. He accused me of abandoning my parents in their time of need. He framed my surgery as a “medical appointment.” He noted the years they had “sacrificed everything” for me, a list that included driving me to soccer practice in eighth grade.

My cousin Michael, who lives near my parents and owns a landscaping business that keeps half the neighborhood green, wrote back: “Uncle Robert, didn’t you just buy a new boat last month? And Aunt Diana, wasn’t that a new diamond tennis bracelet you had at Thanksgiving?” The reply‑all button acquired a special sparkle that day. Private messages poured in—some furious on my behalf, some gentle with questions. Aunt Patty called and, for once, asked me what had actually happened. When I told her, she was quiet for a long time and then said, “Oh, honey,” like she had finally found the note the song needed.

Meanwhile, my life was getting larger in ways that felt like stolen land returning to its original owners. Valerie connected me with a support group for young widowed parents, and on Tuesday nights I joined a grid of faces on Zoom—Diana with the careful hair and the real estate license; Malik, who learned to make fish sticks in an air fryer and called it a victory; Priya, whose daughter refused to sleep unless she could touch Priya’s elbow. We told the truth in short sentences. We learned to laugh again without apology.

Diana came to coffee and never left my life. She studied my apartment like a set designer and said, “You have equity here and prices are leveling in Henderson. Let’s get you a yard.” A yard felt impossible, like a movie set or a word from another language that doesn’t exist in English. But Diana was a widow who had rearranged her life with a toddler in tow, and she made a spreadsheet that looked like something a reasonable person might leap from.

I also started building memorial websites, the idea blooming from the one I made for James—photos and stories and the right kind of music and a guestbook that didn’t feel like a funeral home. People in the support group asked quietly if I would make one for their person, and then the people who came to those sites asked quietly if I would make one for theirs. I never advertised. Grief, it turned out, is a referral business built on trust.

By spring, the twins could climb playground steps like sherpas. We spent two Saturdays touring houses. The third Saturday, we found it: a modest three‑bedroom in a neighborhood where the mailboxes matched and the kids’ bikes lay in front yards like punctuation. The kitchen had a window over the sink that looked out on a patch of grass so small it felt like a joke and so real it felt like a prayer. A neighbor had hung an American flag that snapped smartly in the breeze. On moving day, three people brought casseroles and one man in a Raiders hoodie fixed a loose cabinet hinge without being asked.

The first night, after the twins fell asleep under a new roof, I sat on the back step in the dark and listened to sprinklers tick in a rhythm I did not know I needed. The air smelled like cut grass and something sweet from a neighbor’s grill. My phone buzzed with a text from Jessica: “I fought with Mom and Dad. I told them they were wrong. I’m at a hotel. Can I come by tomorrow?” I typed back, “Yes. Noon.” Then I put the phone down and practiced being a person whose boundaries had the same solidity as her bones.

The collapse of my parents’ finances did not happen all at once, though they narrated it like a natural disaster. There were, it turned out, choices underneath the weather. They had taken a second mortgage on the house a year earlier to buy my father’s boat, a gleaming white testament to his belief that he could outrun time in ten‑knot increments. They had signed a timeshare contract in Laughlin whose fees increased with the calendar, not with their income. They counted my monthly transfers as income. When those vanished, the math turned; it refused, rudely, to balance itself by will.

Jessica called in March, her voice the flat affect of a person trying to be both messenger and sister. “They got a foreclosure notice,” she said. “Sixty days.”

“What about retirement accounts?” I asked, bouncing Emily on my hip while Ethan shouted something about a truck in the next room.

“Mostly gone,” she said. “Boat. Timeshare. Some investment Dad’s golf buddy swore would double.” She sighed. “I’m not asking you to help them. I just…thought you should know.”

My parents texted like people who had forgotten the definition of no. They requested specific amounts, then told me their bank’s routing number as if that was the sticking point. My mother texted, “We never thought you’d actually cut us off. We assumed you were angry.” It was the assumption, I realized, that had glued our family together all these years: that my no meant not now; that my need meant later; that my love meant any cost.

They came over one afternoon with a spreadsheet that belonged in a business school case study about denial. “We need a hundred and forty‑four thousand to catch up,” my father said, like he was asking me to spot him coffee money.

I invited them in because I had nothing to hide. The twins lined up crayons on the coffee table like treasures. I gestured to the couch. “What about selling the boat?”

“We’d take a loss,” my father said.

“What about the timeshare?”

“The market is terrible,” my mother said quickly. “Besides, those are our retirement luxuries.”

“Luxuries you can’t afford,” I said. Not unkindly. Just in the language the numbers spoke.

“We could afford them with your help,” my father said. His tone sharpened. “It’s the least you could do after everything we’ve done for you.”

“What, exactly, have you done for me?” I asked. Not as an accusation. As a genuine question I wished I had asked when I was fifteen and wanted permission to go to a movie.

The twins wandered in, Ethan solemn with a truck, Emily yawning so wide her jaw looked like a hinge bent too far. My parents’ faces softened reflexively. “There are our precious babies,” my mother sang.

“They don’t know you,” I said simply. “You chose not to be involved.”

“That’s not fair,” my father said. “We’re busy people.”

“Too busy to help during my emergency surgery,” I said. “Not too busy to ask for money.” I stood. My incision twinged in a ghostly echo. “It’s time for you to go.”

They did, but not before my mother pressed a hand to the doorframe and made a wounded sound. Once, that sound would have undone me. Now I recognized it for what it was: grief at the loss of power.

Three months after my surgery, they sold the house to avoid foreclosure. They moved into a two‑bedroom condo with a view of a parking lot instead of a lake. My father sold the boat at a loss after all. They canceled the cruise and told everyone they had done it as a moral stance because “family drama” had made the timing wrong.

At barbecues and bridge nights, they told anyone who listened that I had abandoned them. “After everything we did,” my mother would say, hand to chest, nails perfect. The people who had read the email thread did not meet them where they wanted to be met. Some were correctly polite. Others were quiet in that particular way that says, We have revised our opinion.

Meanwhile, my world grew roots in its new soil. The memorial websites multiplied—not in a way that felt predatory, but in a way that felt like building benches on a trail so people could rest. I interviewed a man named Glenn whose wife, Marta, had taught third grade for thirty‑eight years and kept a secret stash of stickers in her desk for kids who had a hard day. I built a site for a woman named Shondra whose brother, Desmond, had written little songs for each of his nieces so they would know their names were music. The work was holy in the way ordinary things are holy when you pay attention.

Diana found me a backyard swing set on Marketplace and negotiated it down by an absurd amount because she can talk any number into a smaller number if the reason is children. Olivia taught Emily to pour from a tiny pitcher without flooding the table. Ethan learned the word excavator and used it at every possible opportunity.

On a sunned‑out June afternoon, a letter arrived in my mailbox with my mother’s handwriting on the front. I almost threw it away unopened, then didn’t. Inside was an apology shaped like a person who had finally learned what a mirror does. “I’ve had time to reflect on my behavior,” she wrote. “Watching you build a life without our help has forced me to confront some painful truths about myself as a mother. I resented your independence. I wanted to be needed in ways you didn’t need me. When you asked us to care for the twins during your surgery, you were reaching out, and we failed you completely. I am deeply sorry.”

She went on to say that my father had taken a part‑time job at a hardware store and that they had sold most of their luxuries. She did not ask for money. She did not ask for forgiveness. She asked for acknowledgment of her apology, which is not the same as absolution but lives on the same street.

Jessica, when I showed her the letter, raised an eyebrow. “They’ve been talking about writing for weeks,” she said. “Dad had a heart scare last month—high blood pressure and chest pains. He’s on medication. It shook him.”

I took a walk that night through the cul‑de‑sac, past the house with the Patriots flag and the one with the succulents lined up like soldiers. The air smelled like someone’s dryer sheet and someone else’s basil. I thought about forgiveness as an economy. Who was I paying? What did I owe? What currency did I want to use? I wasn’t ready to answer. But I was ready to meet.

We chose a quiet café near my house with a chalkboard menu and a barista who knew the regulars’ names. I arrived early and sat where I could see the door. When my parents walked in, I barely recognized them. My father looked smaller without the house around him like armor. My mother wore simple clothes that fit a person instead of a photograph.

We sat. We didn’t hug. The coffee was hot enough to build a small fog above the lid.

“I’ve been a terrible father,” my dad said, and his voice broke the way a branch breaks under honest weight. He cried. I had seen him yell and seethe and recite grievances like scripture. I had never seen him cry. “I don’t expect your forgiveness,” he said. “I just want you to know I see it now.”

My mother nodded, hands flat on the table like she wanted to show me she wasn’t hiding anything. “We started therapy,” she said. “It was Jessica’s idea. We fought it at first. It’s helping.”

I told them about the twins—how Emily put stickers on the dog at the park, how Ethan could identify five kinds of construction equipment. I told them about the memorial sites and the Tuesday night grid of faces that had saved me. They listened without interrupting. They didn’t ask for money. They asked, at the end, if they might know their grandchildren one day.

“That depends on your actions, not your words,” I said. “We can start with short, supervised visits. No surprises. No guilt. If you respect me, we’ll go from there.”

On the way home, I drove the long way so I could pass the house with the sunflowers that tried to outgrow the fence and the corner pie place with the chalkboard that always spelled pecan two different ways. The sky was the pale blue of a TV show’s idea of a sky. My chest felt like a room whose windows had been opened for the first time in years.

The first visit happened at the park in late July, when the swings were too hot to touch and the slides promised second‑degree burns if you were careless. We met under a ramada with a pitted picnic table and a breeze that smelled like two parts sunscreen, one part spilled Capri Sun. Jessica came and so did Olivia because we agreed neutral is sometimes a person.

My parents brought a bag of library books and a cautious enthusiasm. My mother knelt the right distance from Emily and let her come closer by choice. My father asked Ethan about his truck and actually waited for the answer. It was a short visit—forty‑five minutes, measured by the arc of the sun on the concrete. When it was over, Emily waved solemnly like she was sending off a ship. Ethan said, “Bye,” and then, as if remembering something important, added, “Excavator.”

In the car, Jessica exhaled so hard she fogged the window. “That went…not terribly,” she said.

“Not terrible is a win,” I said. We laughed then, the kind of laugh that is release more than humor.

Over the next months, the visits grew like seedlings—tentative, watered, protected from fools who might step on them. My parents showed up on time. They brought snacks we had approved. They sent a picture book about feelings and not a thinly veiled morality tale about obedience. The twins learned their names. I watched my parents try. It didn’t erase what had happened. It didn’t remove the fact that a surgery had been met with a setlist. It didn’t rewrite a ledger. But life, I learned, is more interested in the daily practice than the official record.

On Halloween, Ethan was a construction worker with suspenders he refused to take off. Emily was a giraffe with a tail she tried to share with strangers. My parents came by for twenty minutes and admired the costumes. They left with a photo I took on my phone and printed on the little portable printer I bought for memorial events. The picture wasn’t proof of anything except the instant it captured, which is all a picture ever is.

Thanksgiving came and went without an explosion. We ate at Diana’s because she had the biggest table and the softest way of making space. Malik brought a vat of mac and cheese so comforting it could have been prescribed. Valerie came after her shift with a pie she swore she didn’t bake and then admitted she did. We went around the table and said what we were grateful for, and when it was my turn I said, “Boundaries,” and everyone laughed and then nodded because sometimes the truest things sound like jokes first.

In December, a year after the night with the tinsel garland and the voice that ricocheted off my screen, I took the twins to the same hospital to donate teddy bears to Pediatrics. We walked past the fifth‑floor nurses’ station and left a tin of cookies with a note for Valerie. The lights still buzzed. The garland was new. Olivia held Emily’s hand and pointed out a snowflake made of white paper that some volunteer had cut with devotion.

On the way out, Ethan pressed his face to the glass and watched the city sparkle like it had forgiven itself. “Lights,” he whispered, reverent.

“Yes,” I said. “Lights.”

I glanced at my phone. No missed calls from numbers I feared. A text from Jessica: “Want to do pancakes tomorrow?” A photo from my mother: the twins on Halloween, printed and framed, sitting on a not‑expensive end table I didn’t recognize. My father had written on the back in careful block letters: OUR GRANDKIDS. He had underlined it once, as if making sure the word held.

Outside, the Strip roared its secular carol into the winter air. Inside, my heart felt like a house with the heat on and the lights steady, not an empty warehouse echoing with demands. Freedom wasn’t the absence of obligation, I realized; it was the presence of a life I had chosen—children who knew love was a language spoken daily, work that dignified grief, friends who showed up, a sister who learned a new way to be a sister. My parents were learning too—slowly, imperfectly, in the way people learn when the story they’ve told about themselves finally fails to hold.

When we got home, I tucked Ethan and Emily into their beds and listened to them breathe, that old hymn. Then I went to the kitchen and wrote a list on a sticky note because the woman I had become loved lists: buy more milk; finish Shondra’s photo gallery; text Jessica in the morning; call Diana about the fence; schedule park visit for Saturday; remember to print more flyers for the support group memorial night; wrap the twins’ mittens in the drawer so they’d be a surprise. The list made me feel like the universe had been sorted into parts I could carry one at a time.

I stuck the note to the fridge next to the Hoover Dam magnet and the photo of James in the hospital, ridiculous with joy. “We’ll build our own family,” he had promised. I touched the corner of the picture and felt the steadiness he had always sworn was mine. He had been right about the door in the hallway of my morphine dream. This one had led to better, not because better was owed to me or because the people who had hurt me had suffered, but because I had finally stopped auditioning for a role I didn’t want and started living the one I had.

When I turned off the kitchen light, the house settled around me with the warm little creaks of a place that knows who lives there. Outside, somewhere on the other side of the dark, the city kept singing to itself about luck and games and bright chances. Inside, my life kept time with something older: the metronome of two soft breaths and a clock on the stove that blinked 12:00, 12:00, waiting for someone to set it to the hour of our choosing.

News

While the entire ballroom was applauding, I saw my mother-in-law quietly drop a “white pill” into my champagne flute — she thought I’d drink it; I swapped the glasses and smiled; she raised hers, the music jolted to a stop, every eye snapped our way — and that was the moment the wedding turned into an unmasking no one saw coming.

At My Wedding Reception, My Mother‑in‑Law Slipped Something in My Champagne—So I Switched Glasses I saw her hand hover over…

“My Dad Works at the Pentagon,” a 10-Year-Old Said. The Class Laughed, the Teacher Smirked—Ten Minutes Later, the Door Opened and the Room Went Silent.

When the bell for morning announcements chimed through the beige halls of Jefferson Elementary, Malik Johnson straightened in his seat…

My dad dragged me across the driveway by my hair for blocking my sister’s car…

My dad dragged me across the driveway by my hair for blocking my sister’s car. The gravel scraped beneath my…

END OF IT ALL – I was told over and over again that I was not welcome at any family events. My mother yelled that events were for real family only.. So when I got married I didn’t invite them and they went crazy asking to fix things but I called such a call

I was taught early that belonging had rules nobody bothered to write down. You learned them by touch: a hand…

On My 29th Birthday My Parents Ignored Me And Sent My Sister To Hawaii — “She’s The One Who Makes Us Proud.”

The morning I turned twenty-nine, my apartment sounded like a paused song. No kettle hiss, no buzzing phone, no chorus…

My wealthy grandmother said, “So, how have you spent the three million dollars?” — I froze right there at graduation — and my parents’ answer silenced the entire family…

The graduation ceremony stretched across the manicured lawn like a postcard of American triumph—burgundy and gold banners, folding chairs squared…

End of content

No more pages to load