The morning I turned twenty-nine, my apartment sounded like a paused song. No kettle hiss, no buzzing phone, no chorus of notifications leaping across the screen like confetti. I lay still, listening for proof that I mattered to the people whose names had shaped me into something useful and quiet. The radiator ticked once and fell back into its thin winter breath. Outside, January washed New York in a clean, colorless light—the kind that shows every streak on a window and every truth you pretended not to see.

I reached for my phone anyway. Habit is a soft leash. The lock screen was a flat pane of nothing. I thumbed into the apps and found the first wound where I knew it would be—Instagram—and there it was: a carousel of sun and ocean and my mother’s sunglasses catching a white flare of Maui noon. My father’s hand on my sister’s shoulder. My sister’s smile angled toward the horizon, her boyfriend’s grin wide enough to feel like a dare. The caption, a little poem of preference: Surprise trip for our girl. She’s the only one who makes us proud. Hearts, champagne bottles, hibiscus emojis. And below, my mother’s comment, bright as a blade: She deserves the world.

It took half a breath for the words to settle into the shape of what they meant. Not a mistake. Not an oversight. A decision—a neat, public one—and the way the screen lit my face in that chilly morning turned me into a small aquarium where the fish swam in figure eights around my name.

I put the phone down and watched the steam on the window fade. My name is Maya Hart. I make numbers behave for a living. I shepherd budgets into cohesion and track risk the way sailors watch weather, feeling shifts before they strike. They think that means I’m careful. “Desk job for people who play safe,” my father calls it when he’s performing expertise in things he’s never done. But numbers are lines you can walk like alleyways; there are corners and cut-throughs and doors you only notice when you stop apologizing for what you know.

I made coffee. I fed the pothos and whispered to the aloe the way my grandmother used to talk to pepper plants in Ohio, coaxing fruit from dust. And then I sat at my kitchen table and opened the bank portal for a fund called Family, all caps, a bland noun that had once meant trust. Five years of deposits, crisis patches, careful reconciliations. Five years of me turning my weekends into triage and my savings into stopgaps. My sister’s rent the winter she didn’t like her boss. My mother’s crown replacement after a crack. My father’s surprise LLC fees because a friend had said opportunities don’t wait and, besides, “Maya can handle the paperwork.” Maya did. Maya handled the paperwork and the penalties when the friend disappeared like fog.

I moved the cursor to the button that looked like a dull piece of office furniture: TRANSFER. Full. Confirm. There was a clean quiet to it, like finishing a room after you move the couch and find what collected beneath it—the dust, the single earring, the penny stuck to a melted gumdrop of unknown origin. I made a new account in the name of my business, the thing I’d built on evenings no one asked about. I closed the laptop and told the room out loud, “You wanted pride. You’ll get silence instead.”

Rain started as if I’d knocked on the sky. Not a storm, not an argument—just a steady applause against the glass. I let it play. Somewhere over an ocean, my parents ordered a first round of vacation drinks. Somewhere along a strip of beach, my sister posed with a hibiscus tucked behind her ear, and a man who thought he could save her from consequences pressed his mouth to her temple for the camera. My phone lit with the first emergency call by noon.

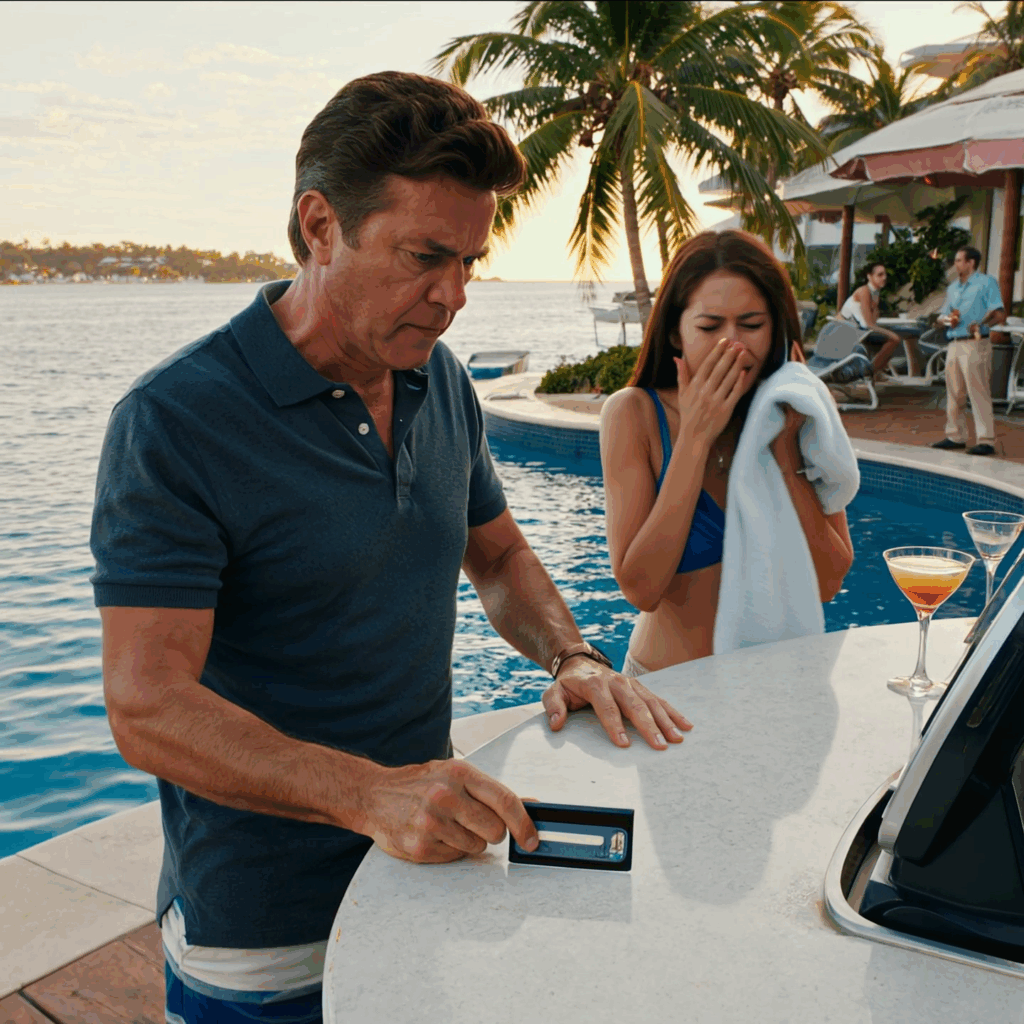

“Something’s wrong with the card,” my mother said. No preamble, no hello. Her voice carried the tremor of a woman whose life is a series of rooms where the lights come on when she claps. “They declined us here at the pool bar. Can you check the account?”

“I can,” I said. I swiveled gently in my chair to look out the window at the city and let my breath even out. “Though—I’m a little confused. Didn’t you say online that I wasn’t part of the family anymore? ‘The only one who makes us proud’—remember?”

“Oh, Maya.” The syllables swelled with the management of a problem she hadn’t scheduled. “Don’t be sensitive. People exaggerate on social. Your sister needed this. She’s been working so hard. Don’t turn this into a thing.”

“I see,” I said. “Just like I exaggerated when I covered your mortgage last spring? When I helped Dad with those quarterly tax estimates and then got to explain to a man named Carl why an ‘opportunity’ fee was a fantasy?”

Silence answered. The kind that opens a trapdoor under everything you’ve been balancing. Then the voice I grew up arranging myself around snapped into shape. “You’re selfish. You chose now—while we’re finally taking a break—to make some kind of scene.”

“No scene,” I said, and found myself smiling, the same small, practiced smile I wear in conference rooms when a man takes my idea out for a walk and brings it back claiming it learned that trick on its own. “Enjoy the sun, Mom. You’ve earned it. Going forward, your pride can pay its own bills.”

I hung up. I blocked the family thread. I set the phone face down and learned the topography of relief—the way it begins as guilt unwinding, then finds its own shape like a river claiming a deeper bed.

That evening, I poured myself a glass of red and opened my journal. Under the date, I wrote: Let them feel what I felt—unseen, unheard, unappreciated. And then: When they call back, it won’t be for love; it will be for money. I promised the page I would answer in kind: with silence, or, when necessary, with records.

By morning, my voicemail was a chorus. My father’s anger wore his old varsity jacket: all swagger at the shoulders, threadbare where accountability should be. “What did you do?” he demanded to the digital void. “Fix this before your mother has a breakdown.” He had never learned to ask whether I needed anything because his world had been edited so that women are furniture until they become faults. I made toast. I let him repeat himself into the speaker a second time and called it music. Later, my sister sent a paragraph that smelled like the perfume of a popular girl in middle school: cloying, confident, a little mean. Grow up. You’re ruining Mom’s trip. You don’t even have a family of your own, so stop trying to control ours.

I typed: Enjoy budgeting. I hit send and put my phone in a drawer.

The bank was a high-ceilinged rectangle of glass and hushed carpet, the kind of space that makes money feel like a language you need a tutor for. I sat with a clerk who wore kindness like a badge and opened accounts in the name of the consultancy I’d nurtured on nights after the firm’s fluorescent hum had scraped the color from the day. “Starting something new?” she asked.

“Ending something old.”

When I got home there were thirty-six missed calls, a number that used to make my stomach fold in on itself. I watered the snake plant and answered none of them. I fried an egg. I took the hollower parts of the day and filled them with small competent acts until I could hear my own thoughts without their interference. It was such a simple thing, to let the world be small enough to fit inside my apartment for a night.

On day three, a friend of my mother’s who lives for broadcasting other people’s plot points posted a shaky story from a poolside bar. In it, my father’s voice boomed in the background, my mother’s hands cut the air in furious little slices, and my sister tried to cry pretty into a phone that could not love her back. I watched once, then again, and marveled at how they made a stage out of any room—how they had taught me to offer up my own labor as lighting.

At noon, an email came. Subject: Disappointed. The body was a tight little paragraph my father had written with the same care he gave notes to contractors—mathematical, defensive, pretending to be professional. We’re disappointed in you. Your actions are unforgivable. Family doesn’t betray family.

I typed a reply that tried. I deleted it. Then I attached a single PDF: FIVE YEARS OF TRANSFERS, line after line of numbers that had shoulders and knees and ragged little hands when you looked closely enough—rent, medication, “temporary loan,” “emergency,” “we’ll pay you back,” “opportunity fee,” late fees from old bills no one had opened because the envelopes had made them anxious. The note I added was six words: Family doesn’t exploit family either.

By evening, the email showed as opened seven times. My aunt Melinda called to whisper the news like a neighborhood watch meeting. “Your dad’s furious,” she said, half scandal and half glee. “Your mom’s crying, your sister’s blaming everyone. What did you do?”

“Nothing illegal,” I said, and for once I heard in my voice the cool laughter of women in movies who finally decided to stop being set decoration. “Just some accounting.”

“Good for you,” she said. “About time someone in that house met a consequence in daylight.”

I looked around at my living room—the good couch I bought secondhand and reupholstered myself, the thrifted lamp that always threw the perfect oval of light, the stack of paperbacks that felt like company. “I’m not standing up to them,” I said. “I just stopped standing under them.”

The feeling that filled me wasn’t anger, or even victory. It was a precise, almost elegant calm. I’d been taught the value of money by people who wielded it like a leash. What I learned by myself was the cost of neglect, public and private. And I hadn’t even sent the surprise yet.

Two weeks later, when their island fun had turned into a slow-motion crash, my father called from an unfamiliar number. His voice had that careful tone it gets when he recognizes the distance between what he wants and what he can demand. “We need to talk,” he said.

“About money,” I said, “or family?”

“About fixing this.”

“There’s nothing to fix,” I said gently. “You broke it years ago. I just stopped patching it.”

“You think this is strength?” he said, soft venom. “It’s cruelty.”

I wanted to tell him that cruelty had always been what you called women’s boundaries when they finally held. Instead, I said the plain thing: “It’s clarity.”

That night my sister wrote, quieter this time. Between us—Mom’s comment was wrong. I’d be hurt too. It was the first true thing she’d sent me in years. I answered: I’m not angry anymore. I just stopped financing my own rejection. Then I attached the receipt I’d been meaning to make: $10,000 from the defunct family fund to a nonprofit that teaches girls finance with the urgency of self-defense. Caption: Better investment.

I didn’t expect forgiveness. I didn’t design this for applause. The next month unfolded like a new street you start walking because all your old routes lead past houses where someone shouts your name like it’s a summons. Work shifted under me in a good way. A promotion went public I hadn’t told anyone to expect; my face appeared on the firm’s website under a bio that finally felt almost true. At night, I drafted the curriculum for a workshop series I’d wanted since college—Financial Literacy for Women Who’ve Been Made to Feel Like a Wallet. It sounded unmarketable. It felt like rescue.

At the first session, in a library basement that smelled like glue and stubbornness, a woman in her thirties asked, “What made you start this?” The old answer lined up: I believed in numbers the way some people believe in prayer. The real one waited behind it: I had a family who taught me debts you can’t put on paper. “Time and care,” I said. “That’s what my grandfather taught me mattered. I’m here because someone tried to take both, and I need to live in a world where girls get to keep theirs.”

They nodded in the soft chorus that happens when strangers recognize your map. On my walk home through a city that smelled like rain warming on concrete, I felt my life click like a seatbelt. Later, there was an envelope in my mailbox without a return address. Inside: a photo of me and my sister as kids on our old porch, ice cream melting down our wrists, our heads leaning together because that’s where gravity used to pull us. On the back, in my mother’s hand: We went too far. I’m sorry.

I did not cry. Grief didn’t feel like a tide anymore. It was a drawer I could open and put something inside, then close and return to when I had time to name it. I filed the photo in a folder labeled Past and pushed it to the back of the cabinet.

The next morning my sister texted again. Mom’s quieter lately. She wants to talk. No pressure. I typed: Tell her I hope she’s okay. I’m okay too. That’s enough for now. Then I took my coffee to the fire escape and let the steam wash my face while the sun found a cut in the clouds and pressed its palm there.

Peace didn’t mean reunion, I was learning. It meant not needing one.

Six months later, I stood on a stage in San Francisco beneath a banner that said Reclaiming Power, Money, Boundaries, and Self-Worth, and told a room of women in blazer-dresses and sneakers what happens when you learn to build without applause. The lights were kind. The mic held steady. When I finished, the applause came anyway, soft then swelling, and I felt not triumph but gravity. Afterward, a young woman with a notebook clutched to her chest said, “My mom says I owe her everything. Even my paycheck.”

“Start by owing yourself peace,” I told her. “That’s the first debt you pay.”

In my hotel room, the bay narrowed the city into lines of light, steady and unbothered. My sister texted to ask if our mother could come to one of my sessions. She’s been following your work. She said she’s proud. The word didn’t pierce me. It hovered, harmless. Thank her for me, I typed. That’s enough. I muted the thread and turned the lights off and let the window keep shining like something earned.

A year later, on a rocky beach in Greece I’d chosen because I wanted a coast I didn’t have history with, I celebrated a birthday with sand in my shoes and no audience. I read. I watched the tide pull its braid of foam and thought of every version of me that had carried groceries and expectations and told herself this is how love works when love has terms and conditions in fine print. My phone chimed twice. The first was from the accountant for the foundation I’d started six months before. The scholarship fund is now active. Three recipients selected. Happy birthday, Maya. The second was from my mother. We saw the news about your program. We’re proud of you.

I wrote back: Thank you. I hope you find your own peace, too. Then I put the phone face down and let the night clean the sky.

Freedom, it turned out, didn’t sound like a door slamming. It sounded like the long, low hush of a tide at rest. I thought that would be the ending, but endings are just rooms with another door marked next.

When I flew home, the city met me with exhaust and pigeons and the complicated affection of a place that had taught me resilience by not caring whether I had it. At my office, they’d hung a banner that made me blush. Congratulations, Maya! The team clapped, and Sam from Compliance brought a cake big enough to be a wedding tier. “Speech!” someone shouted, and I found the three sentences my heart knew, bone-deep: Thank you. I’m proud of what we build here. And I’m done apologizing for knowing what I’m doing.

That would’ve been a tidy arc if life loved tidiness. The week after the cake, a notice arrived at my door in an old-fashioned envelope with the name of a bank that liked to pretend it had existed before money was invented. Inside: a letter informing me that my parents had opened a dispute. They claimed I’d improperly moved funds from the family account—a nice euphemism for the bank drawer I’d managed under my name with their full knowledge because “Maya handles the money.” The letter requested a response.

I stood at my kitchen counter and let a fear I thought I’d retired stretch its fingers. Old dread is an athlete. It knows the path to your throat. Then I set it down next to the letter and laid out what I had: signatures, emails, shared logins, texts that could be read as permission, receipts longer than old novels. I called my lawyer—because this, at last, was a chapter where I could afford one—and sent a wooden crate of documentation.

“Clean,” she said after an hour, her voice brisk and a little admiring. “They don’t have a leg under the table.”

“What if they flip the table?” I said, and surprised myself. “What if the story in their heads doubles as reality for someone in a back office?”

“Then we walk in with the whole room,” she said. “You’ve been doing their bookkeeping and the emotional labor. You’re not doing the fiction too.”

We sent the packet on a Monday. On Wednesday, the bank folded with a quiet that felt like a formal bow. The letter of withdrawal included a line I read three times because it was something I never got from my family: We appreciate your thorough records.

The next message was from my sister. I didn’t open it right away. I washed dishes. I made the bed. I stared at a chip in the paint near the bathroom door and thought about how many times I’d brushed past that spot rushing to be what someone needed. When I finally slid my thumb over the screen, her words were small: I’m sorry. I knew about the account. I should have said it. Mom and Dad… they want me to ask you to forgive them. I’m not asking you that. I’m asking if you can forgive me.

Forgiveness is not a math I could do in my head. It’s a handwritten ledger you keep coming back to and adjusting as the light changes. I wrote: I forgive you for not being older than you were. For not seeing what you weren’t taught to see. That isn’t the same as forgetting. But it’s a start.

Her reply came back as a photo: us again, older this time, arms wrapped around each other at some long-ago Thanksgiving before boyfriends became ceilings and expectations turned into scaffolding. She added: I keep thinking about ice cream on the porch. Do you remember how fast ours melted because we were laughing?

Yes, I typed. I remember you tipped your cone, and I stuck my tongue out and saved the scoop before it hit the steps.

She sent a crying-laughing emoji and then, like a child making a new plan for tomorrow, asked if I wanted to meet for coffee the next time she was in the city.

Maybe, I said. Not yet. But maybe.

The program grew. I watched girls who had been told their voices were receipts speak into microphones and sound like brass. I sat in rooms where women corrected their own narratives mid-sentence and felt the air change as they claimed a whole new tense—future perfect: I will have built. And late at night, when the old ache wandered through, I told it gently that it could rest. We were busy.

Spring made a soft promise of itself across the blocks near my apartment. Daffodils in public beds, a dog that wore a sweater for no reason but joy, a man singing off-key and somehow perfect at the corner by the bodega. On a Sunday, I took the train out to Rockaway and let the ocean smooth the edges of my week. A bird picked a fight with its reflection in a car mirror and won. A child dragged a plastic shovel through the sand like a small plow. I watched the water and thought about how many birthdays I’d sat by a phone waiting for proof that I mattered to people who loved what I did for them more than they loved me.

My phone buzzed. I didn’t look. I watched a wave finish itself instead. The tide pulled back and came again—the original patience. When I finally glanced down, it was a number I didn’t have saved. The voicemail that followed was breathy and halting in a way my mother’s never was. “Maya,” she said. “We went too far. We know that now. Or I do. I… I’m proud of you. I’ve always been, I just… I didn’t know how to be the kind of mother you needed. I’m learning. If you ever want to have tea—no pressure. I’ll bring the good cups.”

I saved the message. I didn’t return it. Not then. Healing wasn’t a game of tag. No one had gotten home; no one was safe. It was a long distance with water breaks and no medals. I walked back up the beach and bought a paper cup of lemonade that tasted like summer and plastic and being twelve on purpose.

In June, the foundation announced the first scholarship recipients. Three girls stood on a small stage in a community center gym under a banner that fluttered every time the AC kicked on. Their families cheered the way mine used to cheer for my sister at meets, and I clapped until my palms burned because sometimes you get to invent the room that didn’t exist for you. After, one of the mothers took my hands in both of hers and said, “You have no idea.”

“I have an idea,” I said, and we laughed through something that was not funny at all.

On the train home, the city slouched against the windows in that golden, forgiving way it has at seven in the evening when the stoops look like possibility. I watched the lights blink on in apartments where people were arguing or forgiving or making pasta, and thought maybe that was the whole point: to build a life that felt like the good part of a long day, earned and intimate and no longer auditioning for anyone.

At midnight, back in my apartment, I lit a candle because I like to keep one lit on days when someone in the world has chosen themselves. I poured a small glass of wine and whispered the private liturgy of my new religion: Boundaries are love with measurements.

It didn’t fix old things. It didn’t wipe a slate. It did something more honest. It let me hold who I had been—a daughter, a sister, a ledger—without folding her into a shape that fit someone else’s pocket. It let me keep the piece of me that had stood on a January morning in a cold apartment and found the courage to choose my own birthday gift. And it let me say, without apology or adornment, the most beautiful sentence I know: I am mine.

The night hummed its steady city hymn. Somewhere uptown, a siren drew a quick line through the quiet. Somewhere downtown, someone laughed the kind of laugh that starts a story you tell for years. I blew out the candle and watched the smoke climb in a perfect gray braid. In the soft dark after, I could almost hear the ocean again, how it keeps returning without needing to be invited, how it wears the rocks smooth without ever raising its voice.

Happy birthday, Maya, I told the room. Then I turned out the last light and let the peace I’d earned make its own weather around me.

By the time spring dressed the city in soft greens, the story the internet told about me had shifted the way a rumor changes shoes. It started with a cousin of a friend posting a status that sounded like a parable told sideways—“Funny how some people forget where they came from”—and ended with a thread on my father’s Facebook where he played the tragic patriarch whose ungrateful daughter “stole” family funds. He used ellipses like he was leaving room for reason to arrive later. Old neighbors chimed in. Men who still wore their high school rings thumped their chests in the comments. Women’s names I remembered from childhood birthday parties appended “praying for you.”

I didn’t respond. My aunt Melinda texted a screenshot with a flame emoji and the words: Want me to start a bonfire? I wrote back: Let the wind do it. She sent three laughing faces and, an hour later, a photo of her toes on a Florida beach with the caption: Airing out the drama.

At work, my days lengthened into a rhythm that felt like a second skin. The new title on my email signature meant more rooms where decisions grew, more hands asking for the numbers to be a prediction that could absolve them of choosing. I wore my hair up. I wore flats because no one with a calculus problem cares whether you squeak when you walk in. On Tuesday mornings, I ran the literacy workshop in the library basement, then hurried fifteen blocks to a conference room where men with blue ties said things like “let’s socialize that risk” and “can we translate that into something the board will believe?” I translated. I did not apologize for the price of accuracy.

One evening, after a session where a nineteen-year-old named Jasmin wrote her first realistic budget and looked at me like I’d given her a spell, I found a letter under my apartment door. No return address, only my name in handwriting that was careful but unpracticed, like its writer didn’t send many letters. Inside, a single page: Ms. Hart, my sister told me about your program. She said it helped her hand back the wallet to a man who kept asking for her life in installments. Thank you. If you ever need a space for your classes, my church has a room we barely use. It smells like old carpet and hope. Call me—Pastor Denise.

The next Tuesday, twined with scent of coffee grounds and the metallic tick of a heater that had outlived three pastors, we moved the workshop to that room. The first night we ran late on purpose. Women stayed to talk in clumps, hands fluttering, the air shifting as if we had opened a window in a house that had never known how to breathe. When the last chair was stacked, Pastor Denise walked me to the door. “I don’t know what your family thinks of all this,” she said, a gentle question folded behind her smile. “But I know what this room thinks of you.”

I thought of my mother’s voice on the beach—We went too far. I’m proud of you. The words sat inside me like a seed sheltered by even, patient rain. “Thank you,” I said, and pretended my eyes were watering because of the cold.

The legal skirmish with the bank ended the way little wars sometimes do: in a file cabinet with a stamp. My lawyer called to tell me their claim was formally withdrawn. “If they push on another door,” she said, “call me. But they won’t. They’ve learned where the cameras are.” I didn’t ask which cameras she meant—the documentation, or the world. Both were turning in my favor, or perhaps just slowing to my speed.

A week after that, my father texted from a number I didn’t recognize. It read: Enough. You made your point. Come home for Sunday dinner. We’ll talk like adults. There are sentences so neatly built you can hear the chair being pulled out for you in a room you have no intention of entering. I hovered my thumb over the keyboard and then set the phone down. An hour later, after I’d folded laundry and learned the names of the new plants sprouting on the median, I wrote: I don’t want to talk like adults. We are adults. And adults decide which tables and which rooms they sit in. I hope you have a kind evening.

No reply arrived. That had always been our vocabulary, really—his silence working like punctuation. I made a baklava from a recipe I found in a Greek woman’s blog and sent half to my neighbor Mr. Duffy, who had lived on the second floor for forty years and liked to pass along the local gossip in the tone of a newscaster breaking something global. He knocked ten minutes later to return my plate with a napkin on top and a small brass key underneath.

“For the roof,” he said, as if I’d asked. “No one uses it anymore. The view’s good for thinking. And for not thinking.”

Under a high, clear sky, the city spread itself out like a map I knew by fingertip. The river cut its patient path, the bridges sutured boroughs to each other, and somewhere far in the west, the day burned down to a band of orange that made the windows shimmer. I let a wind so clean it felt like a blank page run across my face and told the skyline, in case it hadn’t heard, “I am mine.” The buildings didn’t bow or applaud. They simply held.

In April, my sister came to the city for a conference that taught people how to speak in more confident sentences for money. She texted to ask if I could meet for coffee. I said yes, and drew a boundary before the door had the chance to appear. One hour. A daylight café. No surprise guest stars. She arrived in a camel coat and boots that made a sound like intention on tile. Her hair was cut blunt at the shoulders, that universal woman’s signal for shedding something.

“You look good,” she said.

“So do you,” I said, and meant it. We ordered Americanos and a lemon bar for the table. We used to split everything that way, down the line, equal and obvious. She held the tiny fork like a pencil. “I left him,” she said, staring somewhere past my ear. “After Hawaii. It was like… I saw myself from the outside for the first time. I didn’t like the angle.”

I pictured her on a beach chair, the blue world behind her, the phone in her hand reflecting an expression she’d thought she could keep private even from herself. “I’m glad,” I said.

“I got a job,” she said. “Not at the dream company. I answer emails and apologize for shipping delays. But it pays my rent and my own card doesn’t cry at the register. I’m trying to learn money like it’s a language instead of a catastrophe.”

“You can come to a workshop,” I said. “Or not. I’ll send you the workbook.”

She nodded, eyes glossy but not breaking. “I was unfair to you,” she said. “Mom says I was a kid. But I wasn’t. I was a person who chose what was handed to me because it was easier than reaching for anything else. I keep thinking—if I had to raise a girl, I wouldn’t want her to learn she had to earn her place in her own family.”

We talked for longer than an hour. We did not fix anything. We didn’t need to. When we stood to leave, she hugged me with the full weight of herself. “I don’t know what I’m supposed to do next,” she said into my shoulder.

“Not supposed to,” I said. “Choose to.”

That night, she sent a photo of an empty dresser with a caption: My own place. The drawers shone like a row of clean teeth. I Hearted it. Sometimes that’s the whole ceremony.

The next invitation arrived printed on cotton paper the color of pearls. Mrs. Hart, it read in a cursive that looked like it had been taught by someone who owned a bell collection. You are cordially invited to the annual Women in Finance Gala to receive the Beacon Award for Community Education. A woman from the board called to confirm—“We’re so impressed by your work”—and I wanted to say that if they’d been impressed when I was twenty-three and raising my hand in rooms where no one looked up, the entire economy might have been kinder by now. Instead, I bought a simple black dress with pockets deep enough to hide a lucky coin and learned how to walk in heels again with an online video narrated by a ballerina who reminded viewers that balance is not magic, just physics.

On the night of the gala, the ballroom smelled like orchids and new money. I wore my grandmother’s small gold hoops and the red lipstick I reserve for the version of me that refuses to apologize. A woman with a diamond so large it could redirect satellites introduced me with words like “tenacity” and “vision” and “grassroots.” When it was my turn at the microphone, I looked out at a sea of eyes and thought about the women in Pastor Denise’s room, the kids at the community center with their hands up, the girl in the mirror on my birthday morning who had learned that silence can save you if you choose it.

“I’m honored,” I said, and meant that part. “But I accept this for the women who won’t be invited to speak here yet. We’re building rooms for them. We’re teaching that budgets are not punishment— they’re permission. That boundaries are not walls— they are doors with our names on the keys. And that pride is not the opposite of love. It’s the shape love takes when it finally remembers itself.”

The applause rose, neither thunderous nor polite—something human in the middle. After, a man whose cufflinks cost more than my rent told me his daughter could use a mentor. “She’s so sensitive,” he said. “We’re looking for someone to toughen her up.”

“I’m not a toughness vendor,” I said, smiling just enough to pass. “I’m in the business of giving women back what the world borrowed without asking.” He looked puzzled the way rich people do when a product won’t fit into their cart. I excused myself to the ladies’ room and, in the mirror, touched the little hoop in my ear and thought, Grandma would’ve liked this lipstick.

May arrived with a parade of small weather miracles—the day the park smelled like lilacs, the night a thunderstorm passed over without breaking and left the air tasting like metal. I kept my roof key by the door and learned the exact time the lights on the bridges warmed from yellow to gold. On a Saturday, I took the train out of the city to the town where the house I grew up in wore the same paint but different curtains. My mother had been texting me in lowercase lately, as if humility were a font. tea? she’d written. just us. I’ll bring the good cups.

We met in a café that used to be a hardware store. She arrived ten minutes early in a blue sweater I recognized from a Christmas I’d spent memorizing the differences between giving and gifting. She looked smaller without the house around her.

“I don’t know how to do this,” she said as soon as we sat. “I practiced—” she waved a hand, tiny, desperate “—but then I saw you and the words I learned fell out of my head.”

“You don’t have to perform it,” I said. “Just say what’s true.”

She took a breath that tugged at something in my chest. “I was wrong,” she said, eyes not leaving mine. “About what love is. About what money means. About you. I wanted—” Her voice broke in the middle like a dropped plate. “I wanted to be proud of a story I understood. Your sister fit that story. You didn’t, and instead of learning a new story, I tried to rewrite you.”

I waited. The room was quiet in the ordinary way of a Saturday afternoon—a man in a ball cap reading a paperback, a girl biting into a croissant like it owed her nothing.

“I’ve been going to a group,” she said finally. “Not a formal thing. A circle in a church basement. We sit on folding chairs and talk about what we don’t know. I didn’t know how to mother a daughter who didn’t need rescuing. I made you pay for that ignorance. I am sorry.”

I had imagined this scene too often to count. In most versions, I was eloquent. In some, the lighting was excellent. What I felt instead was a simple opening—a window raised in a stale room. “Thank you,” I said. “That counts.”

She reached for my hand. I let her. Her skin was thinner than I remembered, her veins a little roadmap of years I hadn’t noticed while I was busy fixing everything. “Do you hate me?” she whispered.

“No,” I said, surprised by how quickly the answer arrived. “I don’t hate you. I’m careful with you.”

We talked about small things—what the squirrels had done to her bird feeder, whether dry shampoo is witchcraft. She asked about the program, and I told her about Jasmin and the budget that made her cry because it meant she could breathe next month. When we stood to leave, she took a velvet pouch from her purse and pressed it into my palm.

“Grandma’s sewing thimble,” she said. “You used to put it on your thumb and pretend it was a knight’s helmet.”

I laughed and it surprised both of us. “I’m more CFO than knight.”

“Maybe the same thing,” she said. “Different armor.”

We walked to the door together. At the threshold, she looked at me the way you look at a lake you used to swim in and aren’t sure you’re allowed to touch anymore. “If you ever want me at one of your things,” she said, “I’ll sit in the back and clap.”

“I’ll let you know,” I said, meaning the words like a promise to a calendar no one else could see.

On the train home, I cradled the thimble in my palm. It was dented along one edge where a thousand tiny pricks had pushed against it. Protection isn’t always pretty. It just keeps you from bleeding on the thing you love.

In June, the city shrugged into its humid uniform. The workshop moved to later evenings so the room could keep a little of its cool. A new student arrived—a woman in her forties who sat with her spine straight and her notebook on her lap like a shield. On the second night, she stayed after, eyes fixed on the math she’d done in the margin. “If I leave,” she said softly, not looking up, “I can afford a studio in six months if I stop paying for his truck.”

“Whose truck?” I asked.

“My husband’s,” she said. “It’s in my name because his credit is a rumor. He says I owe him for the years he put up with me when the babies were loud.” She glanced up then and I saw it—the place women go when they have finally added it up and the total is themselves. “I thought debt was proof of love,” she said. “It’s not.”

“No,” I said. “It’s just debt.”

She smiled like something heavy had slipped to the ground without shattering. “You make it sound easy.”

“It isn’t,” I said. “But it’s simple.”

She came back with an envelope a week later and slid it across the table like contraband. Inside were three things: a letter to the bank removing herself from the truck loan, a schedule of payments that would turn into a savings account, and a house key with a tag that read For later. We both pretended not to cry.

At work, the quarter closed with a noise like a satisfied exhale. My team shipped a model that predicted churn with eerie precision and saved us enough to earn me a seat at a table closer to the window. I didn’t text my parents. I did text my sister, who replied with a line of fireworks and the words: proud of you in a way that did not make me flinch.

July found me on the roof most nights watching heat lightning play silent tricks above the skyline. Mr. Duffy would sometimes bring a folding chair and a story about a neighbor who kept a parrot that swore in three languages. He was the kind of man who liked to pretend he’d seen it all so he could be delighted when he hadn’t. “You think you’ll ever go back?” he asked one night, meaning home, meaning the version of my family where I played both the electric company and the rug everyone wiped their feet on.

“I went for tea,” I said. “It was good. It was incomplete. That’s probably the shape of it.”

“Everything’s incomplete,” he said. “That’s how the light gets in.”

August took me to three cities in five days for a series of panels where I said sentences about pay equity into microphones that turned my voice into a public instrument. In Detroit, I met a woman who had started a company making steel-toed boots in sizes that actually fit women’s feet. In Portland, I sat with a coder who wrote an app that translated legalese into plain language. In Atlanta, I listened to a high school senior recite a poem about cash and power that left the entire auditorium standing as if we’d been called to attention by a bell we hadn’t realized we could hear.

On the last night, in my hotel room overlooking a freeway that never slept, I opened my journal and wrote: I used to think pride sounded like someone saying my name into a microphone. It sounds like giving other people a microphone and learning I don’t need to hear my name at all. It sounds like my own quiet room. It sounds like the ocean inside my chest when I tell the truth.

September came with the smell of new pencils and possibilities. The foundation announced five more scholarships and a partnership with a bank that had learned to put women in front of the camera as well as behind it. The photo on the press release captured me in a navy dress, my eyes half-closed because I was laughing at something Jasmin had whispered to me. My mother texted the photo with a single heart and a line: I like your hair like that. I stared at the screen and felt something unclench. I wrote back: thanks. Lowercase. Enough.

In October, on a rainy Friday, my father called. I let it go to voicemail and listened while I made a grilled cheese. His voice had shed all its angles. “I was cruel,” he said. Short. Plain. Like the confession of a man disarmed by his own mirror. “I said things to make myself feel big. I don’t know how to be small. I’m trying. If you ever want to show me the budget you teach those girls, I’ll sit down with a pencil like it’s first grade.”

I didn’t expect to cry. I didn’t expect not to. I saved the voicemail next to my mother’s and made myself eat the sandwich while it was hot. Grief has terrible timing. So does joy.

By December, the city wore its annual necklace of lights. I put up a small tree on the radiator cover and hung exactly seven ornaments: three from thrift stores, one from a friend’s trip to Santa Fe, two we made as kids, a tiny glass heart Aunt Melinda had bought me at a gas station in Sarasota because it made her laugh to think of hearts under fluorescent hum. I invited the workshop cohort to a potluck. They brought casseroles and courage and a tin of cookies decorated like little spreadsheets. We danced badly and loudly to a playlist that insisted survival is a hook you can sing.

Near midnight, when the last of them had gone, I stood at my window with a mug of peppermint tea and watched the steam make little moons on the glass. My phone lit with a text from my sister: Family brunch on New Year’s Day at Aunt Melinda’s? Small. No grand gestures. I typed: I can do small. Bring crossword puzzles. She texted back: deal.

New Year’s Day arrived muted and kind. Aunt Melinda’s house smelled like coffee and butter and the kind of warmth you don’t earn; you’re just given it because someone decided you get to be held. My mother wore an apron and laughed too loudly. My father asked me three questions about my work that did not end with the word “but.” We did a crossword on the kitchen island, our heads bent over the puzzle like a congregation. Five letters, it read. “Self-respect.”

“Pride,” my sister said, penciling it in.

“Not the bad kind,” my mother said, eyes on mine.

“The necessary kind,” I said, and let the pencil fill the squares.

We did not talk about money. We did not talk about Hawaii. My father carried my plate to the sink and washed it like it was a sacrament. My mother pressed leftover scones into my hands the way she used to tuck notes into my lunchbox in second grade: You’re brave. You’re bright. You’re mine. The difference now was that I didn’t need the last one to feel the first two.

On my way out, my mother slipped something into the pocket of my coat. In the car, I pulled it out. A photo, crisp and new—the three scholarship recipients standing under a banner that read Better Investment. In the corner, in parentheses, my mother had written: I’m learning.

Winter taught me again how to take daylight in small portions. The roof was suddenly an Arctic outpost. I walked anyway, watching the breath ribbon in front of me, counting chimneys like old-fashioned scores. On a night when the moon looked like a coin someone had rubbed between their fingers for luck, I took Grandma’s thimble from the little bowl by my keys and put it on my thumb. I pressed it to my heart the way you press a seal into wax. Not to close anything. To mark it as mine.

My birthday returned, not like a loop but like a tiny planet making another revolution, its own gravity now. I booked a train to a northern shore where the beach was more stone than sand and the gulls behaved like critics who had seen better days. There was a cottage with wide windows and a kettle that took its time. I brought a stack of novels, a new pair of wool socks, and a plan that involved nothing but a walk, a nap, and a bowl of soup that promised to be exactly what it said it was.

On the morning I turned thirty, I lay in the quiet and waited for nothing. It came like an honest friend and sat with me, open and ordinary. I made tea and took it outside. The ocean was a flat pewter plate. The wind moved across it in visible gusts like the muscles under a horse’s skin. I said my small liturgy: Thank you for what I kept. Thank you for what I let go. Thank you for what stayed.

My phone buzzed. I didn’t look right away. When I did, it was a string of messages:

From my sister: Happy birthday. The first line of that poem you like: “I am water where I wanted to be fire.” Proud of you. Always.

From my mother: Happy birthday, Maya. I made your lemon cake. I broke it taking it out of the pan. We ate it anyway. I hope your day is sweet even if it isn’t pretty.

From my father: Happy birthday. Thank you for the budget. I got to line 8 before I had to call your mother for a calculator. Progress. Love, Dad.

From Aunt Melinda: Another trip around the sun, baby. Keep collecting the light.

From Pastor Denise: The room asked me to tell you the heater rattled tonight and we cheered. Come see us when the daffodils blink.

From Jasmin: I got the apartment. I signed my name like a promise.

I sat on the cold step and let the messages stack into a story I could carry. None of it erased the old script. That wasn’t the point. The point was that I had written a new page and the ink had held. The wind lifted the edge of my scarf. The kettle sang in the little kitchen behind me like an old song that had finally learned my name.

I walked the beach later, hands in my pockets. The rocks were slick and small, the kind that shift under your feet so you have to keep adjusting, a dance my body understood. At the far end of the cove, a child in a blue hat built a wall against the tide and laughed every time the water made off with half his work. He kept rebuilding. Not because he thought he’d win, but because he liked being a person who tries. His mother called him in. He waved at the ocean like an equal.

On my last night, I lit a candle in the window because I’d read somewhere that sailors used to look for them the way we look for Wi-Fi now. The flame leaned in the draft, a small, stubborn star. I opened my journal and wrote one sentence at the top of a clean page: I didn’t become hard. I became clear. Then I wrote under it the names of the women from the room, the ones who had taught me new ways to count. I wrote my own name last, not as an afterthought, but because for once I had remembered to save something for myself.

When I came home, the city was still itself—too loud, too beautiful, too much, a mirror I chose to love because it didn’t lie. I put the thimble back in the bowl, the award on a shelf where it caught afternoon light, the roof key on its hook. I checked the bank account for the foundation and smiled at the numbers there—not because they were large (they were), but because each digit was a woman’s hour, a girl’s textbook, a month of groceries someone didn’t have to ask permission to buy.

I stood at the window and watched the crosswalk fill and empty, the choreography of strangers making a life side by side without needing to know each other’s middle names. I thought about the girl I had been standing at the window a year ago, the blue glow of a screen telling me exactly where I stood in a story that didn’t have my face in it. I touched the glass, cool and solid. “We did it,” I whispered. Not a victory lap. A roll call. A census of one.

The kettle hissed. Somewhere below me, a car alarm cleared its throat and thought better of it. Somewhere above, a plane stitched a white seam through the sky. I poured the tea and sat at the table I had bought with my first promotion, the one that used to wobble until I learned how to tighten the screws.

Peace isn’t a finish line. It’s maintenance. It’s checking the bolts when no one’s watching. It’s oiling a hinge so a door you love won’t stick. It’s washing a cup and drying it and setting it on the counter and knowing it will be there in the morning.

I picked up my pen and began a list of the next right things: Call Pastor Denise. Order more binders for the workshop. Email the bank about the partnership for the spring cohort. Buy new light bulbs. Replace the dying aloe. Text my sister a recipe for lemon cake that leaves the pan without breaking. Send my mother a photo of the ocean.

Outside, the light moved from white to gold without asking for permission. I lifted my cup in a quiet toast to the room, to the roof, to the city, to the country that had taught me to spell “independence” with a flag and a bill and a stubborn will. To Grandma, whose thimble had kept so many sharp things from drawing blood. To the girls who would sign their names next year. To the woman I had become who could finally say without fear or apology: I am not your wallet. I am not your silence. I am not your emergency plan. I am my own plan.

Happy birthday, Maya, I said again, not to mark a date, but to recognize a practice. Then I turned toward the door and the day and all the unglamorous work of keeping a life soft and strong. The ocean in me answered—steady, patient, returning—and I understood at last that this was the only applause I’d ever need.

News

While the entire ballroom was applauding, I saw my mother-in-law quietly drop a “white pill” into my champagne flute — she thought I’d drink it; I swapped the glasses and smiled; she raised hers, the music jolted to a stop, every eye snapped our way — and that was the moment the wedding turned into an unmasking no one saw coming.

At My Wedding Reception, My Mother‑in‑Law Slipped Something in My Champagne—So I Switched Glasses I saw her hand hover over…

“My Dad Works at the Pentagon,” a 10-Year-Old Said. The Class Laughed, the Teacher Smirked—Ten Minutes Later, the Door Opened and the Room Went Silent.

When the bell for morning announcements chimed through the beige halls of Jefferson Elementary, Malik Johnson straightened in his seat…

My dad dragged me across the driveway by my hair for blocking my sister’s car…

My dad dragged me across the driveway by my hair for blocking my sister’s car. The gravel scraped beneath my…

END OF IT ALL – I was told over and over again that I was not welcome at any family events. My mother yelled that events were for real family only.. So when I got married I didn’t invite them and they went crazy asking to fix things but I called such a call

I was taught early that belonging had rules nobody bothered to write down. You learned them by touch: a hand…

My wealthy grandmother said, “So, how have you spent the three million dollars?” — I froze right there at graduation — and my parents’ answer silenced the entire family…

The graduation ceremony stretched across the manicured lawn like a postcard of American triumph—burgundy and gold banners, folding chairs squared…

Graduation day. Grandma asked one question: “Where is your $3,000,000 trust?” — I froze — Mom went pale, Dad stared at the grass — 48 hours later, the truth evaporated into view…

The graduation ceremony stretched across the manicured lawn like a postcard of American triumph—burgundy and gold banners, folding chairs squared…

End of content

No more pages to load