The helicopter’s rotors wound down like the last word of a rumor. Golden-hour light pooled on the red carpet unfurled across the rooftop helipad, and Charlotte Hayes stepped out as if she’d been walking toward this moment for six years. Her gown was a clean line of gold that caught every shard of sunset. With her right hand she held Ethan’s fingers; with her left she held Emily’s. The twins’ little dress shoes clicked in careful rhythm, mirrors of each other and of the man whose eyes they shared.

People paused the way people do when a curtain lifts. Phones rose. The city pressed close from every direction—midtown’s glass canyons, the river beyond, the endless hum of taxis threading the avenues below. At the edge of the helipad the elevator doors waited open, two attendants already whispering to each other.

“Isn’t that—” one of them started.

“Charlotte,” the other breathed. “God. And… are those—”

“Their father will figure it out,” Charlotte said softly, as if the wind had asked. She didn’t hurry. She never hurried anymore. Not through airports, not across streets, and certainly not into the building that bore her former last name on the brass plaque above the revolving doors.

Inside, the Hayes Foundation gala had turned the Carlyle Grand Ballroom into a cathedral for money. Chandeliers hung like harvested constellations. A red silk runner outlined the path to the stage, and a string quartet digested Vivaldi into the kind of pretty that went down easy with champagne. Every donor table carried the name of an oil family, a tech dynasty, or an old-money ghost that refused to stay dead.

Richard Hayes stood near the wings, fingertips on his cuff links the way he touched every edge of a world he believed he’d built. His hair was perfect, his smile prepared in the mirror, his speech arranged to sound unrehearsed. He was about to thank the governor, the chairwoman, the board, and the, quote, tireless staff who made miracles. He was going to say that children’s futures were the true investments—then lean, with pretend humility, into a story about grit he had not lived.

When he saw Charlotte, the lines in his face rearranged themselves faster than words could keep up. Color drained, returned, drained again. He adjusted his cuff links though they didn’t need adjusting. His eyes flicked to the twins and then away as if the view might burn him. Months of rehearsed composure loosened, one invisible stitch at a time.

Charlotte didn’t give him time to find a script. She guided Ethan and Emily between tables where people silently sketched math in their heads—age, resemblance, rumor, risk—and reached the foot of the stage as the quartet’s melody thinned. The emcee, a news anchor with a jawline like a promise, tried to glide into her teleprompter line, but Charlotte placed one palm on the apron of the stage and lifted her chin just enough to take the room.

“Not a guest, Richard,” she said, preempting the joke he had been about to make about surprise. Her voice did not rise; the room simply fell into it. “I’m here to correct the record.”

The emcee blinked. The stage manager gestured furiously from the wings. Cameras re-angled like hunting dogs catching a scent. The governor’s aide whispered to the governor. The quartet stopped without meaning to.

“Charlotte,” Richard said, shaping her name like it might behave if he said it softly enough. The microphone picked up the thin thread of his laugh. “What a—”

“Six years,” she said. “Six years of your story. Tonight I’m telling mine.”

Ethan’s little hand tightened. Emily’s shoulders squared. They did not hide behind her. They watched the man who was not a stranger and not yet anything else. The resemblance was a quick, cruel light—dark hair, exact eyes, a way of standing like every room might be a stage.

Gasps travel differently when they’re not about dresses. The sound reached the balcony and swung back on marble and glass. People were now not just looking; they were choosing sides. Charlotte felt that more than she heard it. She let the weight of the room settle where panic used to live and found that, here too, it had no purchase.

She set her clutch on the edge of the stage, slid out a sealed envelope—the one that had slept in a fireproof box beneath her sink for two months—and placed it in Emily’s hands.

“My daughter,” Charlotte said, “wants to say something.”

Emily had practiced in their living room while her brother watched from the sofa with a solemnity that made him look older than he was. Now she looked at the microphone, at the man onstage, then at the crowd. “We’re not a secret,” she said, voice steady, a small person making a room full of very important people listen. “We’re just kids. He’s our dad.” She pointed with a gravity that should have been too heavy for a six-year-old. “He left before he knew us.”

Silence, then not-silence: a sound like something expensive cracking. Richard moved toward the lectern to reclaim control but found there was nowhere in his body that could carry it.

“DNA test results,” Charlotte said calmly. “Independent. Witnessed. Notarized. The facts you told everyone didn’t exist.”

He nearly reached for the envelope and stopped. He could not afford to look like a man who grabs. He could not afford to look like a man who doesn’t. A board member in the third row—gracious in a way that had always made Charlotte uneasy—leaned back and folded her arms. Two investors murmured into their napkins. A journalist in borrowed black tie slid one step closer with her phone already recording.

A security guard, unsure whether the problem was security-shaped, took a half step as if to shield the stage. Charlotte glanced at him, then lifted her gaze back to Richard. “Don’t,” she said, and for reasons that would take him years to understand, he didn’t.

“Ms. Hayes,” the emcee tried, as if formal address could put the lid back on. “If we—if you’d like to step backstage, perhaps we could—”

“Back rooms are how we got here,” Charlotte said. “We’ll stay in the light.”

She did not hand the envelope to Richard. She handed it to the journalist, whose eyebrows climbed so high they almost touched her hairline. The woman’s hands shook—adrenaline, ethics, ambition all firing at once. She slid the papers out just far enough to catch the lab letterhead, the chain-of-custody signatures, the photographs of cheek swabs and properly sealed vials.

“Enough,” Richard said softly, but the word belonged to someone who still thought language obeyed him.

Charlotte heard Ethan inhale—his brave breath. She squeezed once. “When you threw me out,” she said to Richard, “you said I was nothing without your name. Tonight I returned it to you with interest.”

The line wasn’t rehearsed; it had arrived in the quiet that replaced anger, in a morning making pancakes where the twins debated chocolate chips versus blueberries and she suddenly understood that the future did not require permission.

Flashbulbs chewed the air. The governor decided he had an urgent call and left without looking like he was leaving. The board chair checked her phone, frowned, checked again. In a corner of the ballroom a donor whose money had been old since Reconstruction fixed his eyes on his tumbler to pretend that focus was dignity. People measure risk fast and with their wallets.

Charlotte lifted her chin one more notch and then, astonishingly, stepped back. She didn’t need to watch him fold. She had already seen it in every morning he had not deserved.

When she turned, the crowd divided as if Moses had rolled through Manhattan. She did not hurry. She never hurried anymore. She walked her children out through a world rearranging itself behind her.

The night he threw her out had not happened all at once. That’s the thing about ending a marriage with a weapon—it takes practice. The practice had been little humiliations: You misunderstood the joke. You can’t wear that to my dinner. You wouldn’t understand my work. You are too emotional; you are not emotional enough. A drip, a drip, a drip.

The last night was a flood. It had rained all day, and the city had that after-the-storm shine that makes every street look like possibility. Charlotte had cooked something simple—spaghetti with garlic and lemon and a shower of parsley—because Richard had texted “late, don’t wait” and then texted “never mind, here.” He arrived smelling like money and someone else’s perfume and a bar where the ice cubes had edges sharp enough to say they were artisanal.

He had seen a photo on her phone. Or said he had. Or said he knew what it meant. A friend had sent it—the two of them on a bench in Bryant Park, heads tipped together, summer doing that thing it does to New York when everything feels both eternal and ready to end. She had laughed at a story about a terrible date he’d had before he met his very serious girlfriend now, and someone across the lawn had snapped the moment as if it belonged to gossip.

You betrayed me, Richard had said as if speaking into a mirror. Me. Me. Me. Charlotte had tried to show him the text thread, to explain context, to pull the story out into daylight where it could be seen for what it wasn’t. He had pulled open the front door like a magician making a rabbit disappear.

“Take a bag,” he’d said, so gracious in his cruelty it made her teeth ache. “You can have the clothes you came with.”

She hadn’t told him then that she was pregnant. It felt like saying it would be handing it to him. The elevator doors had closed so softly she had wanted to scream just to wake the building. Instead, she had walked out into a night too big for answers and put one foot in front of the other until her feet learned her future.

Her future did not look like a plan. It looked like a room in Washington Heights with paint the color of waiting rooms and a single window that faced a brick wall that caught afternoon sun like a miracle. It looked like a job at a coffee shop where the owner had named the cappuccino machine Gloria and the dishwasher wouldn’t close unless you leaned your hip into it like a dance. It looked like prenatal appointments on Tuesdays, bus transfers, and learning to carry a water bottle everywhere because pregnancy dehydration was not a myth.

She told no one who didn’t need to know. Not pride. Not shame. Privacy. The kind that wasn’t secrecy so much as the careful tending of something small and growing.

On a Saturday morning, a woman in her sixties took the stool at the espresso bar and watched Charlotte steam milk like art. “That foam,” the woman said. “You make it look like meringue.”

“It’s the pitcher angle,” Charlotte said. “And listening. It… sings when it’s right.”

The woman smiled like she had recognized a countrywoman. “I’m a midwife,” she said. “Fifty babies this year and three more due next week.” She glanced at Charlotte’s belly. “And you?”

“Two,” Charlotte heard herself answer, and the word felt like the truth stepping out from behind a curtain.

The woman—Lois—started coming every Tuesday. She talked about babies who arrived with their fists already open, about mothers who surprised themselves, about fathers who fainted and then cried because fainting had embarrassed them. She never asked about Charlotte’s “situation,” which is what people ask when they want you to supply a story that makes them feel better about yours. She asked Charlotte what she was reading and whether she was sleeping and why she liked lemon in everything.

When the twins came, Lois was there. The city paused the way it does when you bring life into it, and for a whole day the rain forgot how to fall. The delivery nurse hummed Motown while the doctor made a bad joke about Mets fans and pain tolerance. Ethan came wide-eyed and furious as if he had been pulled away from work; Emily slipped out like a secret that had decided to be brave.

On the third night in the hospital, after Lois and the nurse and the doctor and the cafeteria chickens had all done their parts, Charlotte fell asleep for forty-four minutes. She woke to a feeling like someone had poured light into her ribs. There were two humans in the little rolling cribs beside her, and when she touched their impossibly small knuckles, they curled around her finger like a promise.

“Hello,” she whispered, because when you meet two people at once, manners matter. “It’s us against the world for a while.”

The world, to its credit, did not always fight back. Sometimes it helped. The coffee shop owner replaced Charlotte with two part-timers and then quietly paid her during maternity leave anyway. Lois brought casseroles and the names of two pro bono lawyers who handled custody and support for women who did not have the right last name. The neighbor whose wall she shared—a violinist who practiced in the afternoon and never after eight—learned how to hold a baby and then casually asked whether Charlotte would like an hour every day to shower or sleep while he played Bach to them in the blue chair by the window.

The pro bono lawyer who stuck was Maya Albright, sharp as a closing argument and soft where new mothers need softness. Maya didn’t ask about the tabloids or the divorce that Richard had ghost-signed through a private server that spat out settlement offers like a slot machine. She asked about names and birth certificates and what Charlotte wanted her life to look like in five years apart from money.

“Truth on paper,” Charlotte said. “Names matched to facts. And a life that isn’t built around avoiding his.”

Maya nodded, took notes that looked like maps, and then explained the landscape: paternity acknowledgment, voluntary or court-ordered testing, custody agreements that didn’t have to look like anyone else’s, child support guidelines that weren’t bargaining chips but statutes. She never promised outcomes. She promised standards.

“Do you want his money?” Maya asked finally.

Charlotte looked at the twins asleep in their stroller, their mouths making perfect Os like they were practicing astonishment. “I want what belongs to them,” she said. “And I want him to stop living inside my life. He can keep his money. He can’t keep the lie.”

“Then we’ll make the lie expensive,” Maya said. “People like your ex only learn one language.”

The first year was a battle fought in inches: feedings and rest and forms filled out while one baby slept and the other loudly disagreed with the concept of pens. Charlotte learned to sleep in twenty-minute tiles. She learned to cook with one hand, to change diapers like a pit crew, to move through exhaustion like fog until it became landscape.

Once, at three in the morning, she stood at the window and watched snow fall into the very small slice of alley she could see, and she cried without sound, not because she was sad but because she was bigger than she had ever been and there was no room left inside for all of it. Ethan stirred and sighed and went back to dreaming whatever babies dream. Emily’s hand flailed and found Charlotte’s shirt like a climber locating a hold.

In the second year, she took on clients for event design—small work at first: birthday parties for people who wanted the balloons to look effortless, storefront windows for places that wanted to look like they’d been in the neighborhood forever, a fundraiser for the public school where the principal had more spine than budget. She learned which rental company delivered on time, which florist was secretly a poet, which photographer knew how to catch the soft half-smile of a child pretending not to care.

She did not Google Richard Hayes. She did not look at the tabloids that mentioned him. She did not count the women on his arm or the deals he closed or the panels he sat on to discuss ethics in business while the mic pinned humility to his lapel. The world did that counting for her. She counted socks that had lost their mates and the number of stairs to the apartment and the time it took for a child’s tears to arrive and leave.

When the twins turned three, Maya called. “We can test without him,” she said. “His sister posted a photo of their father on a genealogy site. I can get an order for a kinship test. But I want you to make this decision without me pushing.”

“Do it,” Charlotte said, and when she hung up, she sat on the kitchen floor with Ethan and Emily and drew a treasure map that ended in a crooked X. “That’s where the truth lives,” she told them. “Sometimes you use a shovel. Sometimes you use paper.”

The test didn’t sing or flash. It was swabs and seals and an affidavit that read like a librarian listing rules. Then there was the waiting Maya had warned her about—the way the mind makes time into a problem to solve. Charlotte built a fort out of sofa cushions and read The Velveteen Rabbit until Emily insisted the rabbit hire a lawyer and Ethan suggested the Skin Horse run for office.

When the results came, they came like everything important had come: plain envelope, plain language, a fact without adjectives. 99.97%. Maya walked Charlotte through the next steps, then asked again if she wanted money.

“I want legal recognition,” Charlotte said. “Support if they need it, not if I do. His name where it belongs—in a file drawer. But not in my living room.”

“You understand the press might get wind of it if we file,” Maya said gently.

“Then we’ll do it in a way that tells the truth once,” Charlotte said. “On my terms.”

“Your terms will get tested,” Maya said. “That’s what men like him do when they say they love truth.”

“I know,” Charlotte said. “I’ve been tested.”

The plan took shape over months. Charlotte’s gigs grew. A city council candidate whose heart was better than his slogans hired her to turn an empty warehouse into a fundraiser that felt like a block party. A startup that sold very expensive candles—scents like Pine After Rain and A Library That Made You—brought her on to make their pop-up feel like an alternate universe. She learned to trust people who delivered at three a.m. and to ignore those who emailed at five with ideas that meant you would be the one doing the work.

Ethan and Emily started kindergarten with backpacks so enormous they looked like pilots taxiing their own airplanes. They made a friend named Zora who drew superheroes that looked like librarians and a friend named Ben who told everyone the mitochondria was the powerhouse of the cell while refusing to eat broccoli because it looked like trees. They asked questions about everything including why adults forgot to nap and whether the moon got lonely in the morning.

One afternoon, after drop-off, Charlotte rode the subway downtown and stepped into a lobby with a ceiling painted to look like a sky that was better at being a sky than the real one. The Hayes Foundation offices looked like virtue had been poured into glass and chrome and set to chill. She asked for a meeting with the head of communications. She used her married name once, carefully, the way you touch a hot pan to test whether it will burn you.

She had brought her portfolio—beautiful photographs of events that had made people kinder at least for a night—and left it closed on her lap. She did not make small talk about the weather or the headline about a celebrity who had sold a photograph of her pantry. She said, “I have a proposal,” and placed a single page on the table.

It wasn’t a job proposal. It was an itinerary.

“You’re hosting your annual gala in June,” she said. “I will attend with my children. You will turn on the cameras. I will speak three sentences. Then I will leave. You will not escort me out or attempt to move me into a side room. You will let me say the truth once, in public, and you will allow that truth to travel without your commentary.”

The communications director’s mouth fell open and then closed again like she was catching a fish and remembering she didn’t like it. “That’s not how—”

“That is how,” Charlotte said. “I’m offering you the most dignified version of a story you cannot control. You can say you were surprised or you can say you allowed the truth. Choose the one you can live with.”

“You can’t just—”

“I already filed,” Charlotte said. “Quietly. You have a week before the papers hit public view.”

“You’re… extorting us.”

“No,” Charlotte said. “I’m teaching you how to behave.”

The woman stared, and then she did what people do when the path forward only looks like losing less: she said she had to talk to legal. Charlotte waited in the lobby long enough to count the number of donors whose names had more marble than some people had medicine. When the communications director came back, she was flanked by a lawyer who had learned to make compassion look expensive.

“We can’t promise anything,” the lawyer said.

“You can promise you won’t touch me,” Charlotte said. “Or my kids.”

“Of course,” the lawyer said, stung. “We would never—”

“You already did,” Charlotte said, then turned and left before the building could teach her to hate it again.

The night of the gala went how it went: light on gold, a city watching, Charlotte saying the truth once like a bell rung correctly. When she stepped out of the revolving doors into the river of evening, the air tasted like metal and oranges—rain somewhere far off and the citrus from a tray of cocktails inside. Ethan and Emily each took one of her hands, and the three of them moved into the streetlight as if it were theirs.

They took a cab because the twins wanted to watch the little map on the screen redraw the city into dots and lines. “That’s where we were,” Ethan said, pointing to the tiny icon of the hotel. “That’s where we are,” Emily added, tapping the corner by the park. Children are very good at geography when you tell them maps are true more than once.

At home, Charlotte set her phone to Do Not Disturb and put it in a drawer. The world could shout into a pillow. She made grilled cheese with cheddar so sharp it felt like an opinion, and she burned one edge and cut it off and ate it herself. They watched a nature documentary about octopuses because octopuses always look like someone was told to design a creature after having only heard about animals over the phone.

By ten, the twins were asleep, and Charlotte sat on the floor between their beds like she used to when the nights were harder than the days. It wasn’t a prayer, what she said. It was a promise to the air. “We told the truth,” she whispered. “We did it like we said we would. You were brave.”

Her phone, traitorous even in a drawer, buzzed until it had a personality. When she finally checked it, far after midnight, there were texts from numbers she recognized and didn’t—from Lois (“Proud of you, baby”), from Maya (“We did good. Tomorrow will be loud.”), from a woman Charlotte had shared a hospital room with for twelve hours whose baby had been born with a little heart murmur (“Saw you on TV by accident. You looked like yourself.”), from an unlisted number that had sent only: Charlotte. We should talk.

She turned the screen face down, slid the phone back into the drawer, and slept past the sunrise for the first time in years.

By morning, the story had done what stories do when truth and money collide: it ran everywhere. A respectable national morning show ran a segment using words like allegations and claims and said their legal team had reached out to representatives of Mr. Hayes for comment. Three tabloids invented angles that included a yacht, a French tutor, and a distressed trust fund. Anonymous sources lined up to explain to anyone with ad inventory that Richard was a good man who worked too hard and always tipped.

Maya’s office rang off the hook. She let it ring. She called Charlotte at nine. “How are you?”

“Eating pancakes on the floor,” Charlotte said. “We are listening to a playlist Ethan calls Songs That Taste Like Cinnamon.”

“Good,” Maya said, the kind of good that meant keep doing exactly that. “At some point we need to talk about the next step.”

“He texted,” Charlotte said. “Late.”

“What did you do?”

“Put the phone away.”

“Good.”

“What is the next step?”

“He’ll do something ugly,” Maya said. “A suit, a leak, a rumor. He doesn’t know how to not push. You don’t respond to any person who isn’t me. If the school calls, you forward it. If his lawyer calls, you forward it. Do not reply to him. He’ll try to goad you into a mistake that looks like anger. You are allowed private anger. Publicly, you’re a citizen who told the truth and has paperwork.”

“Paperwork,” Charlotte repeated, and it felt like armor.

The ugly arrived before lunch. A gossip site ran a story about Charlotte’s “checkered past” complete with a pixelated photo of her leaving the coffee shop with a bag of day-old pastries she’d been given for free and a caption that made charity look like theft. A different site published a “source” claiming she had been “obsessed” with Richard long after the divorce, which was a curious definition of not thinking about a person.

Maya filed. The filings were not angry. They were precise. They used words like enjoin and misrepresentation and sought immediate relief so quiet you could hear the law clear its throat.

By evening, Richard filed too: a petition seeking a temporary order concerning the children. His lawyers requested a hearing, arguing that the publicity Charlotte had created was harmful to minors who had not chosen public life. Maya read it twice, then called Charlotte.

“This is the move,” Maya said. “We expected it. He’s going to put on his Respectable Father sweater and ask the court to play hall monitor. We’ll bring the test, the timeline, the receipts, and the testimony of a mother who did not seek out a camera until she needed a witness.”

“We’re ready,” Charlotte said. She looked over at the twins, who were building a city out of blocks and naming the streets after desserts. “We’ve been ready.”

The hearing was set for a week later in a courtroom where the pews were always a little too shiny and the clock at the back always ran two minutes slow. Charlotte wore a navy dress that could not be argued with and shoes that wouldn’t punish her for standing. Maya carried a binder whose tabs looked like a rainbow had gone to law school.

Richard arrived with a team that moved like choreography—someone to carry the bag, someone to carry the water, someone to carry the aura of inevitability that money mistakes for virtue. He wore gray and remorse. He did not look at Charlotte; he looked past her like a man staring at a future he was sure would arrive on schedule.

The judge was a woman whose patience had a spine. She looked at the file, looked at the twins’ birthdates, looked at the chain-of-custody documents, looked at Maya like a colleague and at Richard’s lawyer like a person who needed to get to the point.

“Counsel,” she said, and the word sounded like a warning to anyone who might try to make theater out of children.

Richard’s lawyer stood and began a performance about privacy and the hazards of media and the sanctity of childhood innocence. He said harm a lot. He said misguided. He invoked concern like a prayer. He did not say responsibility or abandonment because those words do not bend as easily.

Maya stood and did not perform. She offered the test results and the timeline, the affidavits and the photos, the quietly astonishing fact of six years of parenting without a check with his name on it. She did not call him names. She called the court’s attention to the difference between quiet and secret.

When the judge spoke, she did not glow; judges don’t. “I see two interests here,” she said. “The welfare of the children and the rights of their parents. I see one parent who has been present and one who has been absent by choice. I am not inclined to punish the former for making a public record of paternity when the latter has insisted on a private fiction.” She tapped a pen on the file, three soft clicks. “Temporary orders: paternity acknowledged, interim support calculated per statute, parenting time to begin with supervised visits at the Family Resource Center, media contact by either party is not enjoined but will be weighed in any future determinations. We reconvene in thirty days.”

Richard made the mistake of looking at Charlotte then, reflex instead of strategy. His eyes said what his mouth could not on record: You will pay for this.

Charlotte’s eyes said what hers would not waste breath saying: I already did. Not anymore.

Outside, microphones grew like mushrooms after rain. Maya took them when necessary, refused them when not. Charlotte said nothing. She drove to the Family Resource Center a week later and sat in the waiting room with walls painted colors someone had promised were soothing. Ethan lined up toy cars by size. Emily drew a house with three windows and a cat whose smile took up most of its face.

Richard walked in six minutes late, then pretended he had been early and chose to enter precisely on time. The supervisor—a woman named Alanna who wore her hair in a bun that could survive a hurricane—introduced everyone like they were meeting at a potluck.

“Hi,” Richard said, crouching to the twins’ height because he had read somewhere that this was a thing. “I’m… Richard.” He couldn’t make himself say Dad. The word lived in a part of his mouth that had not learned how to be humble.

Ethan looked at him the way he looked at new foods: curious, wary, polite enough to try. Emily said, “You can call us by our names,” because Lois had taught her that people who call children buddy or kiddo without learning their names were often rehearsing.

They played a board game that had been designed to teach patience but mostly taught boredom. Richard was awkward, then over-compensating, then almost charming, and then awkward again. He asked questions about school that sounded like he wanted answers to a test. He forgot that the thing to say about a drawing is not What is it? but Tell me about it.

At the end of the hour, Alanna said gently, “Next week?” and Richard nodded as if he had a choice.

Back at home, Charlotte sat on the edge of her bed and let the day pass through her. She did not cry, though she felt like it would be a valid hobby. She wrote down what the twins had said when he’d left.

Ethan had asked, “Do we have to like him now?”

“You have to be yourselves,” Charlotte had said. “Liking is a thing that grows or doesn’t. It’s not homework.”

Emily had asked, “Will he be mad if we don’t know how to be his kids yet?”

“He’ll have to learn how to be your dad,” Charlotte had said. “That’s bigger work.”

In the weeks that followed, the board of the Hayes Foundation did its own kind of learning. Donors questioned strategy in ways that sounded like they were questioning morals. Staff circulated an anonymized letter describing a culture that rewarded compliance over candor. A vice president resigned “to spend more time with family,” which was code for You built something I can’t stand up in anymore.

Then, the quiet turn: the CFO requested a meeting with Maya. He arrived with eyelids that looked like he hadn’t slept in a year and a file folder that looked like it had eaten the truth for breakfast.

“I’m not a good man,” he said before sitting. “I’m a man who likes spreadsheets and rules and who learned to ignore certain… smells. But this—” He pushed the file across the table. “It’s not just optics. It’s money. Money moved like water under a door you keep saying is sealed.”

Maya listened the way surgeons listen before cutting. The file contained transfers that didn’t belong where they had landed, reimbursements that smelled like vacations, and two payments labeled Charitable Programming that had bounced from a donor-advised fund into a for-profit entity whose sole asset was a yacht.

“We don’t need this,” Maya said carefully. “This isn’t our war.”

The CFO nodded. “I know. It’s mine. But you should know where the pressure points are as you keep him busy.”

Maya considered a beat too long. “Does your board know?”

“They know the parts they like,” he said. “They don’t know they’ll need lawyers who work weekends.”

The board found out on a Tuesday because Tuesdays are when bad news believes you’ll be too tired to fight. Within forty-eight hours, a special committee formed with names designed to reassure. Within seventy-two, Richard was placed on administrative leave “pending the outcome of a thorough and independent review.” Within a week, a reputable business magazine ran a cover story titled Empire on Ice with a photograph that made Richard look like a man waiting for a bus in a snowstorm in a suit.

Charlotte did not celebrate. People emailed her versions of You must feel vindicated and Sheesh and How about that, but vindication was a poor meal. She made soup. She took the twins to the park. She bought Emily a ridiculous pair of glitter sneakers because she had run hard at recess and scraped her knee and not cried until the bathroom where it was private. She bought Ethan a book of maps because he needed to know how things connected.

At the next hearing, Richard arrived late again and alone. The Respectable Father sweater had been traded for something that looked like apology manufactured in a factory. He asked for unsupervised time. Maya asked for gradual. The judge gave them both pieces of what they wanted and neither of what they didn’t deserve.

On the way out, Richard stopped at the bottom of the courthouse steps. He spoke without looking at Charlotte. “You win,” he said.

“There wasn’t a game,” Charlotte said.

He laughed once, without humor. “There’s always a game.”

“Maybe that’s why you lose.”

He looked at the street. “I didn’t know,” he said, and the words came out small. “About them.”

“You didn’t ask,” she said, and left because some conversations do not require two chairs.

Freedom didn’t arrive as a parade. It arrived as mornings that felt like normal. Charlotte woke to two sleeping children and the quiet of a city before delivery trucks. She made coffee that sang. She met clients who wanted rooms to feel like hope and then made rooms that did. She told the story of that night at the gala exactly twice—to a woman from a domestic violence nonprofit who wanted to understand how to help other women name their terms, and to Lois, who had been there for everything and deserved the whole truth as payment for the casseroles.

She did one more thing: she founded a small program for single parents who needed a hand that wasn’t pity. She called it First Light and funded it with a chunk of the settlement Richard finally offered when his board made clear the legal discovery process could go from civil to criminal if he persisted in being the kind of foolish that comes with a tie. The money went into childcare stipends and legal navigation and a small center with a playroom and a desk where a person who knew things could sit and tell other people who didn’t how to find the door out.

Ethan and Emily grew like hope. They tied their shoes and then forgot how and then learned again. They learned the word adjacent because Ethan liked shapes and Emily liked words and both liked the way adjacent felt like adults forgot how to be near each other. They asked, after visits with Richard that were sometimes good and sometimes not, the question children ask when adults have made new rules. “Is this forever?”

“Nothing is forever,” Charlotte said, “except the part where I’m your mom.”

One evening in late fall, when the leaves had made the park look like a place that knew how to end and begin at once, Charlotte sat on a bench while the twins took turns on the swings. A woman in running shoes slowed and sat at the other end as if benches were strangers who could be friends.

“I watched your speech,” the woman said after a minute.

“I didn’t give a speech,” Charlotte said. “I told the truth.”

The woman nodded. “I left once,” she said. “No helicopter. No microphones. Just a car with a cracked windshield and a cat carrier. I thought I was the only person who’d ever done it.” She laughed softly. “Turns out there are so many of us we could form a parade.”

“Parades are loud,” Charlotte said.

“Sometimes loud saves lives,” the woman said, then stood and ran on, and Charlotte sat a while longer and watched her children fly back and forth in arcs that were everything and enough.

When she tucked them in that night, Ethan asked the question he liked to ask before sleeping because patterns made him feel like the world would still be there in the morning. “What are we tomorrow?”

“Ready,” Charlotte said, kissing his forehead.

Emily, who liked to steal last words and turn them into the beginnings of stories, whispered, “Whatever comes.”

Charlotte turned off the light. She stood at the door for a beat, listening to their breathing settle into the soft chorus she’d learned the first week at home, and felt the quiet arrive like a guest who knew not to knock. She went to the kitchen and wrote three thank-you notes—one to Lois, one to Maya, one to Alanna—because gratitude is the work you do when the miracle becomes routine.

On her phone, ignored until the last minute of the day, a headline waited: Board Removes Richard Hayes as CEO; Foundation Names Interim Leadership; Investigation Continues. She did not click. She did not need to see the ice sculpted into policy. She poured a glass of water and stood at the window and watched the city remember how to sleep.

When Richard’s name appeared on her phone again, she let it go to voicemail. He spoke after the beep in a voice that sounded like a person realizing that the line between apology and nostalgia is thinner than the person apologizing thinks. He said he’d like to talk. He said the kids had laughed at something he’d said that day and that the sound had made him think of summer when he was small and the ice cream truck bells felt like a future. He said he was changing.

Charlotte deleted the message. People can change. They can also learn to act like people who change when courts are watching. She would judge change by the banked repetitions of showing up, by the absence of lies, by the presence of breakfast on a Saturday morning that did not come with a promise attached.

She turned off the kitchen light and walked back to the hallway where the twins’ door stood slightly open because that is the right way to leave a door when you want a child to know that you could come if called. She pressed her palm to the wood like she was feeling the thrum of a house settling. She said the words she had said on a rooftop under chandeliers and in a courtroom under a clock that refused accuracy and in a hospital under fluorescent lights that made everything look too sharp.

“We’re ready,” she whispered. “Whatever comes, we’re ready.”

The city breathed with her. The night held. Tomorrow could bring anything. She had made a life that could hold it.

Months stretched into the kind of calendar that doesn’t need every square filled. The supervised visits ended as the supervisor’s notes turned from anxious to ordinary. The twins learned Richard’s dog’s name and that he made bad pancakes but tried for good ones. They learned that disappointment isn’t a catastrophe; it’s a teacher with a chalkboard voice.

In spring, Charlotte got a call from the museum where she had once been a person who looked at paintings without seeing them. They wanted to commission an installation for a fundraiser: something that felt like return without sentimentality. She built a room of mirrors and light where people could see themselves from angles they didn’t expect. She made a path through it that required people to move slowly. She named it Terms.

At the opening, donors did the dance of pretending they hadn’t read the business magazines. A woman Charlotte had met a decade earlier at one of Richard’s dinners approached with a smile that used to make charcuterie seem political. “You’ve done well,” she said, and Charlotte heard the hidden clause like a stone in a shoe: for someone who fell.

“I’ve done,” Charlotte said. “The adverb changes with the day.”

The woman blinked and then laughed because her brain didn’t know where to hang that sentence. She moved on. People always do.

Lois visited the installation and said she would like to deliver babies in a room like this. “So they can see,” she said, “that the person they’re becoming is already made of angles they haven’t learned yet.”

Maya came on a Sunday morning, when the museum was quiet and the guards had taken to calling Charlotte by her first name. She stood in the middle and smiled like she was looking at a client who had become a friend who had become someone she would call if her car broke down in Queens at three a.m.

“You know the board offered him a consultancy,” Maya said finally.

“Of course they did,” Charlotte said. “They like their villains declawed and on retainer.”

“He turned it down.”

“He’s not done pretending he deserves a throne.”

“Probably not.” Maya tucked her hands into her pockets. “Are you?”

Charlotte looked at the light turning visitors into versions of themselves they might like better. “I am done needing a stage.”

That afternoon, in the park, Emily won a race she had not known she was running and then applauded for the child who came in second because the world is kinder when you act as if there is enough victory to go around. Ethan found a perfect rock shaped like a heart and then gave it to a little boy who was crying because his kite had forgotten how to obey physics.

On the walk home, they passed the hotel where the story had pivoted. The red carpet was gone. The rooftop garden had traded out last season’s flowers for this season’s. A different man in a good suit stood where Richard had stood, practicing a different speech in a town that made speeches into weather.

Emily looked up. “That’s the place,” she said.

“Yes,” Charlotte said.

“We were brave there,” Ethan said.

“Yes,” Charlotte said.

“We can be brave somewhere else now,” Emily decided.

“Yes,” Charlotte said, and they crossed the street on the walk signal because bravery works best with timing.

When the mail came that evening, a thin envelope waited: final orders signed and stamped, names in the places where names go, obligations where obligations live. Charlotte read them once and filed them behind Terms under the letter H because filing under F for Final felt like a dare.

“Is it over?” Ethan asked, reading her face the way he’d learned to read maps.

“Parts of it,” Charlotte said. “And parts we can put on a shelf.”

“What about the other parts?” Emily asked.

“We live them,” Charlotte said. “We make dinner and do homework and forget library day and remember again. We call Lois on Tuesdays and bring her coffee we make too strong. We invite Maya to birthdays and ask her not to bring a briefcase. We visit Alanna on holidays and drop off toys for the waiting room. We build new parts until the old ones are just… background.”

Ethan nodded like a person considering architecture. Emily yawned like a cat and then asked for a story about a girl who loved words and a boy who loved maps and how they once found treasure under a city bench.

Charlotte told it. She made the treasure something ordinary and necessary: a key that opened the big door on a small building where people learned to stand. She made the ending quiet and full: a kitchen with rooms beyond it, a table with chairs pulled close, a window with light that changed but never left.

After they fell asleep, she stood again at the door, palm on the frame. The city murmured. Somewhere a siren practiced. Somewhere a woman said no and meant it. Somewhere a man tried yes for the first time.

“We’re ready,” she said into the house she had made out of bones and chance and stubbornness. “Whatever comes.”

The night did not answer. It didn’t need to. She had already learned how to hear herself.

News

While the entire ballroom was applauding, I saw my mother-in-law quietly drop a “white pill” into my champagne flute — she thought I’d drink it; I swapped the glasses and smiled; she raised hers, the music jolted to a stop, every eye snapped our way — and that was the moment the wedding turned into an unmasking no one saw coming.

At My Wedding Reception, My Mother‑in‑Law Slipped Something in My Champagne—So I Switched Glasses I saw her hand hover over…

“My Dad Works at the Pentagon,” a 10-Year-Old Said. The Class Laughed, the Teacher Smirked—Ten Minutes Later, the Door Opened and the Room Went Silent.

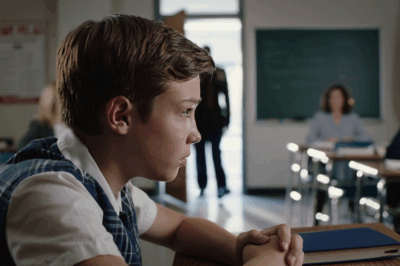

When the bell for morning announcements chimed through the beige halls of Jefferson Elementary, Malik Johnson straightened in his seat…

My dad dragged me across the driveway by my hair for blocking my sister’s car…

My dad dragged me across the driveway by my hair for blocking my sister’s car. The gravel scraped beneath my…

END OF IT ALL – I was told over and over again that I was not welcome at any family events. My mother yelled that events were for real family only.. So when I got married I didn’t invite them and they went crazy asking to fix things but I called such a call

I was taught early that belonging had rules nobody bothered to write down. You learned them by touch: a hand…

On My 29th Birthday My Parents Ignored Me And Sent My Sister To Hawaii — “She’s The One Who Makes Us Proud.”

The morning I turned twenty-nine, my apartment sounded like a paused song. No kettle hiss, no buzzing phone, no chorus…

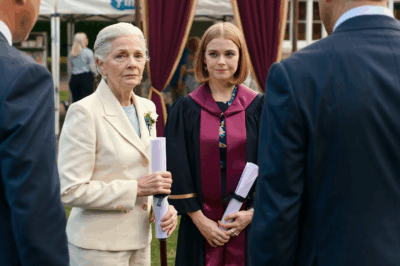

My wealthy grandmother said, “So, how have you spent the three million dollars?” — I froze right there at graduation — and my parents’ answer silenced the entire family…

The graduation ceremony stretched across the manicured lawn like a postcard of American triumph—burgundy and gold banners, folding chairs squared…

End of content

No more pages to load