When the Light Came Back

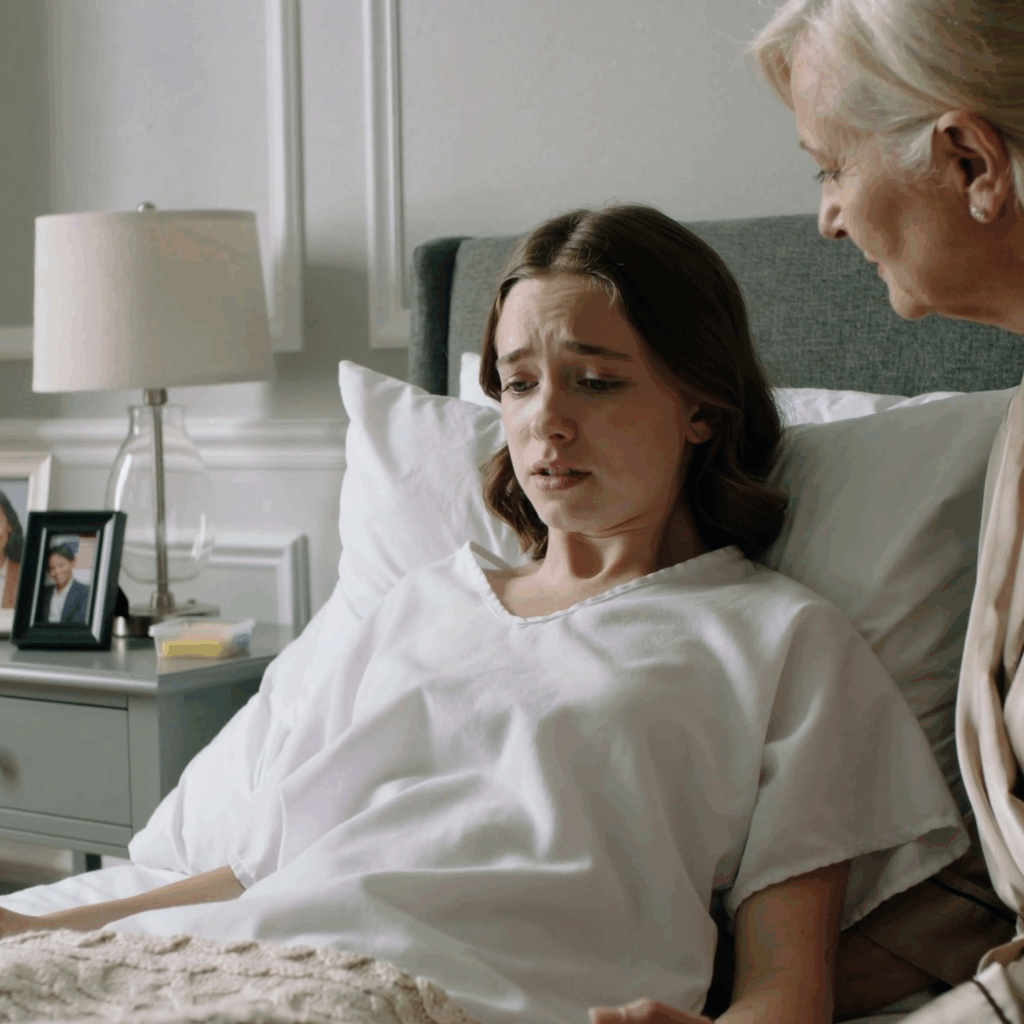

I woke to the rustle of winter light on a hospital window and the slow metronome of machines learning my heartbeat. The white noise felt like ocean surf in a shell. A man was bent over me, his head bowed as if in prayer. His palm cupped mine. I knew his voice before I knew the room.

“Evie,” he whispered. “Hey, sweetheart. You found your way back.”

Caleb. The name slid through my mind with the ease of old habit. A shape followed it—six feet of farm-boy handsome, the kind of face people trust on sight. We’d once joked that if he stuck a jar of honey on a porch with a handwritten sign and nothing else, the whole town would leave money in a coffee can rather than take a free taste.

Behind him, the window held a gray Pennsylvania morning over Maple Ridge, our small town between the river and the ridge, where porch flags clicked against their poles on windy days and the courthouse dome watched over the square the way an old pastor watches a congregation. My body felt like a house after a fire—still standing, but the rooms unfamiliar. My tongue was sand. There was a taste of metal at the back of my throat and a hummingbird panic under my ribs.

“You were out two months,” he said, tears bright in his eyes, thumb moving over my knuckles. “They said it was a miracle you woke up. Don’t try to talk. Just breathe with me.”

His voice was soft and careful, calibrated to the frequency people use around sleeping infants and barn skittish horses. He kept his gaze on our hands, and when a nurse came in—Aimee, per her badge—she touched my shoulder and called me “Evelyn,” the name my mother used when she meant business. Somewhere under the fuzz a memory rang like a fork hitting glass: my full name read aloud at graduations and doctor’s offices, the way Dad’s baritone filled a room. Evelyn Grace Dalton.

“Pain?” Aimee asked. “On a scale of one to ten.”

I tried to say a number. Sound caught behind my teeth like a dry seed. My mouth opened but only breath came. Aimee understood without my saying. She helped me drink, coaxed sips from a straw.

“You’re safe,” Aimee said. “Your dad and mom have been here. Your grandmother too. Caleb never leaves. We’ll keep the lights low. Rest.”

Safe. The word had weight. It pushed on something locked away, the kind of door you don’t open because you learned young not to make a scene at someone else’s table. My mind leaned toward it and then slid off like a boot on black ice.

Caleb kissed my forehead. “I’ll tell them you’re awake,” he said, and the shape of him straightened, shoulders rolling back with relief so visible it looked rehearsed. He moved with certainty, already at home among the wires and beeps, a sentinel who had been standing watch and could finally lower his guard. People love a man like that. The internet loves a man like that.

I slept again and woke to voices. My father’s, thick with emotion he tried to bury and never could when it came to me, his only child. My mother’s careful questions. Nana June’s laugh-sob that had soothed me since kindergarten.

“Hey, baby,” Dad said, leaning in, his eyes rimmed red. “We’re right here. We’re not going anywhere.”

How had I gotten here, I wanted to ask. I could see pieces: flour dust on black jeans, the curve of a rolling pin, ovens bright as planets. Hearth & Honey, the bakery we’d opened on Main Street with a ribbon and a prayer and a list of debts stacked like a layer cake. The oven timers had a song that wormed into dreams. I had been arranging cinnamon buns in a spiral, brushing butter into each coil, the smell of sugar and spice like a hymn, my hair clipped back with a tortoiseshell barrette. Then—nothing.

A week passed measured in therapist visits and brain checks, in tiny victories: lifting a spoon, flexing a foot, remembering the name for “thermometer.” People came to the doorway and stared in with the reverence of parishioners at a miracle. Maple Ridge Daily had run Caleb’s photo next to mine, his hand cradling my bandaged head while he gazed down with the devotion of a painting. The headline called me our town’s sleeping beauty and Caleb, our steadfast prince.

He sat by my bed and told stories the way a person might build a life with matchsticks. He reminded me of our first day in the bakery, when we’d sold out by noon and danced behind the counter, flour on our cheeks. He teased me about my morning playlist—Aretha to Brandi Carlile—and the way I attempted latte art that always turned into hearts when I meant rosettas. I watched the slope of his nose, the set of his jaw, the way he squeezed my hand on the beat of the heart monitor. People brought casseroles and coffee cards and envelopes of cash. The feed buzzed with comments about true love.

Two months is a lifetime when a town is watching. By the time I could string sentences, a narrative had settled over us like a quilt: I had slipped, hit my head, and the man who loved me had carried me through. Every kindness he did became proof. He slept in the chair. He learned the schedules of my meds. He updated a group called Pray for Evie with photos of my feet wiggling under hospital sheets. He wrote long posts about perseverance and hope and the way I looked at sunrise when the window turned rose. He linked to a fundraiser that had blown past its goal, twenty, then fifty, then a hundred thousand dollars, with comments from strangers saying they’d never seen devotion like his.

But memory does not answer to public relations. It answers to the body, which keeps the score, to borrow something my therapist would later say. Mine kept it in small flashes: the slap of dough, the smell of singed sugar, a voice going thin with anger. A single second of sound like a bird hitting glass. I’d reach for it and my mind would fog over. I would lose the word for whisk and call it the spin-thing. I would wake gasping in the night while Aimee rubbed circles on my arm and asked if I wanted her to call my family. I would say no. I didn’t know why. The word no came out as if it had been waiting to be useful.

The day they discharged me, it was snowing. The sky was the color of dishwater and the courthouse flag hung limp in the calm, frost spangling the fence posts along the hospital drive. Caleb insisted we go to our apartment. “It’ll help,” he said gently to my parents. “To be somewhere familiar. I’ll take care of her.”

Dad looked at Mom, a conversation passing without words. He had never liked surrendering me to anyone else’s care; he had built the crib and the tricycle and a dozen bookshelves like fortresses around his girl. But it seemed ungracious to refuse a man who had kept vigil and changed bedpans and taken unpaid leave from whatever job he was saying he had at the plant. He had a way of looking wounded when questioned, as if the very idea that he was anything but heroic was its own injury.

The apartment was the same as before except for flowers. Gerbera daisies glowed from every flat surface like cheerful witnesses. The air smelled like something meant to smell like cinnamon instead of cinnamon itself. My wool coat felt heavy across my shoulders. I took two steps and steadied myself on the back of a chair.

“Home,” Caleb said, the word warm as tea. He shrugged out of his jacket, caught my mother’s eye and softened his voice just enough. “We’ve got it from here. I’ll text you any time there’s a change. She needs quiet.”

My mother nodded, swallowing whatever she might have said. Dad hovered. “You call if you need anything,” he told me. “Anything at all.”

Caleb kissed the top of my head as the door shut and stood there a long moment staring at it. Then he slid the deadbolt, picked up my phone from the kitchen counter, and tucked it in his pocket. He smiled at me. “Let’s get you to bed.”

It took a week before I realized he wasn’t just guarding my rest. He was guarding me. From my parents, who texted and got no reply. From Aimee, who brought soup and left it at the step after no one buzzed her in. From the world that had rallied to my bedside and now watched from the feed as Caleb posted sunset photos and captions about healing and patience. He had my passwords. He had set up automatic postings to keep the story going: a weekly photo of our hands, of the mug he held while keeping vigil, of my slippered feet on the couch.

When I asked for my phone, he said, “Only for a little while. You get overstimulated. We have to protect your brain.” When I asked to see my parents, he said, “They mean well, but your mom’s anxious energy wears you out and your dad wants to fix things and gets pushy. You never liked pushy.” When I said my grandmother always brought calm into a room and could we invite her, he smiled, that small closed-lip smile that meant no dressed in yes. “Soon.”

Food came on a schedule. Pills came on a schedule. Sleep came like a trapped bird, fluttering and frantic. The apartment grew smaller every day. If I opened a window he shut it immediately and said, “Cold isn’t good for blood flow.” Then he switched to a tone that always shut me down: lightly exasperated, as if I’d left the oven on. “Evie, I’m doing everything here. Just rest.”

One afternoon he was late coming back from the bakery. He’d insisted on reopening in a limited way, more to keep the brand alive than to make money. I had suggested we close until spring. He’d laughed like I’d told a joke I didn’t know was funny. I was alone, a silence like stretched elastic in the room. I shuffled to the bedroom closet for a sweater and found a shoebox on the shelf with my name on it in black marker.

Inside were papers. Bank statements. Insurance forms. A printout of my grandmother’s trust. The Dalton Family Trust, established by my grandfather, set to pay me the shares my mother’s side had built over two generations the week I turned twenty-one. Only child, remainder beneficiary—language I had signed on advice from our attorney when I was nineteen and uninterested in anything that didn’t involve yeast or sugar.

A sticky note fluttered out. In Caleb’s upright, neat printing: guardianship petition — file if necessary. Below, a list of steps. Step-one, physician affidavits. Step-two, emergency hearing. Step-three, temporary guardian control of assets. It looked like a recipe card for someone else’s kitchen.

My stomach turned cold. I put the lid back on and slid the box into the far corner of the closet like it was live. I sat on the edge of the bed and stared at the wall until the room steadied. The words arranged themselves. Air went thin.

In the kitchen, the oven timer buzzed though nothing baked. A sound like a bird at glass, then heavier: a roll of wood against bone. The world tilted. The hospital woke inside my head, its smell of sanitizer and lemon clean. The last thing I remembered before the dark was the sound of wood meeting a skull and the way the floor jumped up. I had burned four trays of croissants. I had laughed at the smoke alarm like it was a prank. Caleb had gone quiet and then hot, a simmer-heated anger. “You cost us money,” he’d said in a voice I recognized now as a stranger’s. He’d picked up the rolling pin and his mouth had become a white line.

I went to the bathroom and threw up until there was nothing left. When I stood, the mirror showed me a woman I half knew: cheeks hollow from hospital, hair limp, bruise-yellow faint behind one ear. I touched it. I thought of my father’s hands steadying a ladder, my mother’s voice reciting psalms when storms rolled in, the way Nana June set a pie to cool and it made the whole house smell like mercy. Then I put my back to the door and slid down it to the tile and sobbed without a sound.

He came home with the smell of fryer oil on his coat and the means to make the world believe anything he said.

“You’re up,” he said, too cheerful. “We were slammed. People love the crullers.” He set a bag on the counter. “I brought you a maple bar. You like those.”

It’s a fact about me I had forgotten until he told me. I do like maple bars. I dislike being told who I am when I am right there in the room. I reached for the bag and stirred my voice from wherever it had been hiding.

“I saw the papers,” I said.

He didn’t blink. “What papers?”

“The trust. The guardianship notes. With my name on the box.”

He held my gaze for one beat and then the closed-mouth smile moved onto his face like an automatic canopy. “Evie,” he said, dropping his keys into the bowl with a clatter meant to ground us in domestic normal. “I had to educate myself in case— Look at me. People die every day of less than what you went through. If you hadn’t woken up, someone had to take care of you. The court would expect me to step up.”

“I have parents,” I said, and the words came out like I’d rehearsed them in the dark. “I have a grandmother.”

He shrugged, a lift of one shoulder that tried to make a storm a little weather. “They panic. Your dad gets loud. Your mom cries. Your grandmother’s sweet but she’s ninety-one. I’m here.”

“You’re here,” I said. “Because you put me here.”

For the second time in our life together, his face lost color. It went flat, then emptied, as if he had taken himself off like a jacket. Something colder stepped into the space he left.

“You fell,” he said. “You slipped on butter. I told your father that on the phone the night it happened. There was no one else in the room.”

“I remember the rolling pin.”

“You’re confused.”

“I remember the rolling pin.” My voice shook the walls of me with how hard it tried to stand up. “I remember the sound.”

He smiled. “Memory is tricky after a brain injury. You know that. Aimee said so. Let’s not make a mess of your progress with false accusations. I’ve done everything for you. Everything. Nobody loves you like I do.”

“Give me my phone,” I said.

“I’ll bring it by later.”

“Now.”

He reached into his pocket very slowly, like someone reaching for a snake. He set my phone on the counter as if returning contraband. His eyes didn’t leave my face. “Make good choices, Evie,” he said softly, and it was not advice. It was warning.

When he left for the bakery the next morning, I dialed my grandmother from the landline we kept for storms. My finger shook and mis-punched twice before the third try went through. She said hello in the way she always had, like an invitation into a room where the kettle was already singing.

“Nana.” My voice broke around the word like a wave around a rock.

I lasted six words before she understood. “I’m coming,” she said. “I will be there in ten minutes.”

She arrived in nine, in a wool coat older than I am and a scarf my grandfather had bought her on their honeymoon in Maine. She pressed her cheek to mine and for a moment the smell of her—a mix of rose hand soap and cinnamon—pretty much saved me from drowning. Then she set her hands on my shoulders and looked me over like she could will bone straight and blood strong with her gaze.

“We are leaving,” she said, the plural unarguable. “Mark’s warming up the truck.”

“He’ll be angry,” I whispered.

“That will save us time, then. Get your coat.”

We crossed the parking lot under a sky the color of pewter, our breath white in the air. Dad stood at the curb, jaw set, engine idling, a look on his face I had seen when a neighbor’s dog turned on him once without warning. He opened the door, kissed my forehead, and said, “You ride in the middle. Seatbelt.”

“He’ll come to the house,” I said.

“That’s where he will start learning the word no.”

Mom was waiting at the front door, hands tight around each other as if to keep from reaching out and crushing me. She did anyway. “Evelyn,” she said, tears coming despite herself, and then, because she had always been better at mercy than at fury, she went to the kitchen to make soup, because soup was a thing you could do that made other things bearable.

I told them in pieces. How he moved the phone. How he said I became overstimulated. How sleep fell wrong on me now and I woke with my heart clanging to a rhythm I couldn’t control. How I had found the box and felt the world stand up on two legs under me again. How I remembered the rolling pin. How the story everyone had shared and reshared became a screen between us and the truth.

Dad listened without moving except for the muscle in his jaw. Mom cried the way rain starts: gathering itself, then falling. Nana watched me like a hawk, the kind you’d swear had slow eyes until it moved and you saw the speed was just under the surface. When I finished, she smoothed the hair back from my forehead as if I were a child sick with fever.

“Sweetheart,” she said. “Let’s call Mary.”

Mary Delgado had been our family’s attorney since before I could spell attorney. She wore boots and silver hoop earrings and did not meet problems with squinting suspicion but with clean questions that made people tell the truth to themselves just to be rid of them. She set a cup of coffee in front of me and asked if I wanted her to hold my hand before we began. I did.

“First,” she said, “we get you a protection-from-abuse order. That buys you space. Second, we notify the hospital social worker and your neurologist. If you’ve disclosed and he attempts contact, there’s a record. Third, we freeze any changes to trusts or accounts until there’s clarity.” She looked at Dad. “Mark, you need to call the bank today. I’ll call the trustee.”

“Caleb’s been posting about the fundraiser,” Mom said shakily. “People have given so much. They’ll feel betrayed if—”

“They’ll feel updated,” Mary said gently but with a blade under it. “They feel what they feel. That’s not our work here.”

She turned back to me. “Evelyn, I’m going to ask you to tell me the last day you remember at the bakery before the hospital.”

“The ovens were on,” I said. “I burned croissants. He got… quiet. He said I cost us money.” My breath caught. I reached for Nana and she put her palm on my back and rubbed small circles, steady as the clock tick behind Mary’s desk. “He picked up the rolling pin. He said… he said, ‘You never listen.’ And then he did it.”

“Did he hit you before that?” Mary asked, her voice the kind you use to coax an injured animal out of a hedge.

“He had. Not like…” My mind tried to be loyal to the picture the world had painted of us. It tried and failed. “He broke my phone once when I told him to stop yelling about a game. He shoved me so hard I hit the door jamb when we were arguing about a supplier. He said those weren’t real hits. He called them startles.”

“We’ll need corroboration,” Mary said, nodding like she’d expected that part and hated being right. “Text threads. Photos. Anyone you confided in.”

“I told no one,” I said, shame burning my face as if I had chosen quiet for sport instead of survival. Then I remembered Aimee’s steady hands and clear eyes. “Maybe Aimee suspected.”

“Good,” Mary said. “I’ll call her. And your neighbor? The barber? Anyone with a camera near the back alley?”

“McAllister’s Auto keeps one over their bay,” Dad said, his voice a relief after so much tightness. “Points toward the alley.”

Mary’s smile flashed quick. “Let’s go make friends.”

We learned both less and more than we wanted. McAllister’s had footage of the alley for the week before my fall; the night in question, their DVR had glitched. The world is full of bad timing. But Aimee had noted a bruise on my collarbone two weeks prior. She had charted my startle response when a visitor dropped a tray and a metallic clang made me flinch hard enough to throw a monitor error. She had asked about stress at home and I had said I was fine so politely that she’d written, Patient denies concerns.

Mary filed for the PFA and got it in front of a judge the next morning. The order required Caleb to stay three hundred feet from me, my house, my work, my church, my grandmother’s porch with the geraniums. It was words on paper but those words opened me a little, like windows in July. Mary sent letters to the bank, to the trustee, to the insurance company. She reached the Maple Ridge Daily editor and said calmly that if they wanted to continue to be considered a news source, they might correct their framing.

When Caleb found out, he called from a number I didn’t recognize and left a voicemail with a voice I did. Rage makes bone and metal in a throat. “You ungrateful little—” he began, and said the rest with his mouth too full of hate to contain itself. He ended with the line men use when their mask slips all the way off. “If you take everything from me, I’ll burn you to the ground.”

We sent the audio to the police. Detective Noah Briggs, who had a face like a friendly math teacher and a brain like wire, listened twice and looked up at me from the playback as if gauging the angle of my breakage.

“You ready to tape him?” he asked.

“Excuse me?”

“You be you. He’ll be himself. Sometimes the fastest way to catch a snake is to bring it into the open.”

The idea made my skin go cold. Then it made me feel like I had been under water and come up for air.

We set a date. Not at the apartment or my parents’ house or the bakery. At the high school gym during a community fundraiser for the girls’ basketball team. A public place. Plenty of sound cover. Detective Briggs would be close. I would wear a recorder small as a nickel under my sweater collar. Aimee would be on the bleachers pretending to check a blood pressure cuff.

When I walked into the gym, the squeak of sneakers on polished wood made my stomach flip. The Maple Ridge Christian Academy girls were shooting layups while their coach shouted encouragement. Banners lined the walls: STATE SEMIS 2018. WORK HARD. BE KIND. The big flag hung over the scoreboard, an angled light from the far doors catching it so it looked like it was breathing. I said a prayer that did not bother with poetry.

He saw me a minute after I saw him. He had the look men get when they think they’ve been ambushed and then realize the ambush will let them make a speech. He sauntered over. His hands swung at his sides like a Western sheriff’s. He stopped just short of the distance in the PFA. My recorder got the sound of his breath through his nose.

“You,” he said, a marveling hiss. “You did this.”

“No,” I said. “You did this.”

He tilted his head, confident that whatever angle I chose, his angle would beat it. We stood so near the free throw line we could have called a foul.

“You cost me everything,” he said. “The bakery will fold without me. I kept it alive while you slept like you meant to. Everyone knows who did the work. Ask them.”

“I burned croissants,” I said. My voice was steady in a way that surprised me until I recognized it as the moment when fear gets bored of itself and becomes something else. “You picked up the rolling pin.”

“No one will believe you.” He smiled. “I was the man who loved the broken girl. I changed diapers like a nurse. I rubbed your feet for Instagram.”

“I believe me,” I said.

He leaned in, tiny bit. “You tell anyone I hit you, I swear to God I’ll—”

Detective Briggs arrived at his shoulder, not touching him, just there, like a fact. “You’ll do what, Mr. Ward?” he asked, his voice as mild as a librarian’s.

Caleb’s face did something I had never seen it do. It looked like a boy’s, caught by a principal after cheating when he’d thought the test would be easy. He flicked his eyes toward the door, toward the bleachers, toward the girls running drills. He laughed like something had just amused him that the rest of us had missed.

“She’s exaggerating,” he said. “She falls. She forgets. Brain injuries will do that.”

Briggs extended a card as if they were at a job fair. “Come down to the station. You can repeat that into a better microphone.”

The Maple Ridge Daily changed their headline from steadfast prince to accused abuser in under twenty-four hours. The fundraiser comments evolved from poetry about love to the kind of battle people wage when they feel they’ve been taken. Some asked for their money back. Some said they forgave him. Some argued over whether forgiveness without repentance is just cowardice with a good haircut. I stayed off the feed. I ate soup in small bites. Aimee showed up with a heating pad and candy canes leftover from the hospital tree. We watched old reruns where the laugh track did too much work and I let it anyway.

Mary prepared me for court like a coach prepares a clutch hitter: reps, breathing, a reminder that the plate does not care about your nerves, only your swing. We went over my statement until I could say it without crying and then again until I could say it without clenching my fists. I practiced the phrase “I don’t recall” for places I truly didn’t and learned not to apologize for what trauma stole or hid. The neurologist testified about subdural hematoma and the likely mechanism of injury. Aimee testified about bruises on old skin and new fear in the room. The barber on the corner said he’d heard a shout and a sound like a cabinet slammed three weeks before the fall, and when he’d asked if everything was all right Caleb had smiled and said they were passionate about pastry.

Caleb’s attorney tried to cut our story thinner than it could go. He showed photos of Caleb spooning broth into my mouth and asked the jury if that looked like a man who could be cruel. He emphasized confusion as a symptom of recovery. He called me ungrateful with nice words and made the word ungrateful stand in for liar.

When Caleb took the stand, he wore a blue suit and a Sunday smile and looked at the jury with a softness I had once wanted to move into and live there forever. He spoke about the bakery as if it were a baby we’d made, and about my parents’ caution as if it were hostility. He said I slipped and he found me and the floor was so slick with butter it was no wonder. He said he had loved me so completely he had considered becoming my guardian just to make sure I’d never have to worry again.

“He wrote steps,” Mary said on cross. “A recipe for your money.” She let the box label do the work: Evelyn. Guardianship—file if necessary. She asked him what would make it necessary. He floundered. He found a line. “Love,” he said finally, like he’d landed the trick.

Mary turned to the jury. She did not roll her eyes. She did not need to. “Love,” she repeated, and let the word sit there like something that had been set on the counter and found to be plastic.

He did not confess, exactly. But he confessed to the shape of a man who would do the thing he was accused of doing. He admitted to grabbing my arm until I bruised because I had frightened him by leaving the oven on. He admitted to breaking my phone because I needed to pay attention. He admitted to considering guardianship because a woman like me—emotionally soft, as he put it, a baker not a banker—needed someone practical in charge. He admitted to raising money in my name and using some of it to keep the bakery afloat through doing what he called expansions. He did not use the word lie. He used story.

The jury came back after five hours with a verdict of guilty on aggravated assault and attempted theft by deception. The judge—who wore his robe like a normal jacket, as if he could take it off and put it on a hook and be only himself—sentenced Caleb to three to six years and ordered restitution. He told Caleb that mercy is not the same as indulgence and that repentance without truth is just a habit of thought. Caleb did not look at me when they led him away. He looked at the gallery like a man who expected applause and was surprised by the choke of his own silence.

I shook in the hallway. Mary wrapped me in a hug the way a horse blanket wraps a shivering animal. Dad put his palm on the back of my head and kissed my hair. Mom cried into a handkerchief with pale pink embroidered initials that had belonged to her mother, and the damp spread like a petal opening. Nana stood with her cane and stared down the corridor like an old general after a long campaign.

“Let’s go home,” she said. “There’s pie.”

Healing is a job done in shifts. You clock in. You forget and then remember why you’re there. You clock out to sleep and dream you’re lost on a highway with no lights, then you wake and discover the map under your hand. There were days I hated my own head for its soft places and loved it for the ways it surprised me. I learned my new limits and then tested them like a teenager. Fatigue came like a storm rolling over a cornfield; I could smell it before it arrived. Therapy taught me my brain had rerouted traffic; some mornings we’d find a back road and I’d perform a task like tying my shoes without noticing until after that I had done it.

I went back to the bakery with Dad two months after sentencing. We had closed Hearth & Honey during the trial; I could not stand the sight of the window decal without feeling dizzy. We opened the door and the old bell clanged, the sound almost holy. Light sat on the flour dust like grace on a mess. I ran my fingers over the butcher-block counter and into the groove where a thousand knives had landed. Then I went to the ovens and set one hand flat to the cool metal and promised them we would try again.

We started small. Cinnamon rolls on Saturdays. A dozen loaves of sourdough with the slash marks that looked like old maps. Lemon bars with the powdered sugar shaken so fine it looked like first snow. The town came the way people come to a funeral: carefully, with eyes open, ready to do the work of feeling. They paid with twenties and told me to keep the change. They told me about their daughters and their sisters and themselves. The barber’s wife said she had called the hotline once and hung up and then called again. A teacher said she had written a student a note that said You are not crazy just because you are afraid. A man I didn’t know cried into a bag of poppy seed muffins because his sister had not woken up.

“Put the flag out,” Dad said one morning, passing me the pole we kept by the door. “You always liked the way it looked against the brick.”

I opened the bracket and slid the pole into place. The flag unfurled like it had been waiting for air. People make a lot of promises about flags. Mine was smaller than those promises. It meant we were open. It meant come in.

The inheritance became less like a dragon in a cave and more like a river with banks. With Mary’s guidance, we restructured the trust so that no single person would ever again be able to pull its lever without two signatures and a calendar’s worth of waiting. We set aside a fund for women in Maple Ridge who needed first month’s rent and a cheap flat for three months while they rebuilt an ordinary life. We called it the June Fund because Nana argued and then had to accept that some honors have her name on them whether she prefers anonymity or not.

By July, my hair had grown into something approximating itself—a bob with ideas about curls. My balance was good enough that I could make four pies at once without sitting down. I could make change without writing it on a napkin. I took my phone back and let it be my phone. I learned where the off switch was and used it. I moved into my own apartment over the bakery. The first night I slept above the ovens I woke at 2 a.m. to a smell like butter and metal and for a moment my mind did the old thing, the thing where all hallways become the one you ran down while a voice behind you turned your legs to water. Then a train moaned on the curve by the river and the sound remade the night: ordinary, far away, routine.

People asked if I forgave him. Sometimes they asked with that Sunday-school keenness that forgets time is needed and wounds are particular. Sometimes they whispered it as if forgiveness were a secret code that proved entry. I said that forgiveness changes names as you go. At first it was sunlight through the window on a Tuesday when I remembered how to braid dough and the braid came out even; then it was eating a peach over the sink with juice running down my wrist and letting the sweetness beat the memory of metal; then it was laughing with Aimee in the aisle at the hardware store because we could not find the right size screws and the clerk kept insisting the ones we had would work. It wasn’t noble. It was the business of my life getting bigger than him.

In August, a letter arrived from his mother. She wrote that she was hurt by how I had destroyed her son’s good name. She wrote that she had always thought I was pale and too quiet and that a strong woman would have made a strong man better. She wrote the kinds of things women learn to write when their place at a table depends on agreeing with a man who has made his own story and called it truth.

I set the letter on the counter and made a blackberry pie. The top crust tore when I laid it down. I patched it with a heart-shaped piece cut from the scraps and brushed it with cream and sugar. In the oven, the heart browned first, a small, solid shape. I took the pie to Nana and we ate it on her back porch while the cicadas sang like wires. She did not ask me about the letter. She asked me about the peaches and whether we should put in more geraniums before the fair.

“Do you ever get tired,” I asked, “of being the person who knows what to do?”

She laughed, a sound like a drawer full of silverware gently shaken. “Every day,” she said. “And then again every morning I get up and see that it doesn’t matter who knows what to do. You get up anyway.” She reached over and patted my knee. “You getting up is enough.”

On the anniversary of the day the ovens burned, we held a small gathering at the bakery. Not a grand reopening—those had too much confetti in them, too much insistence. We called it Tuesday. We brewed coffee and set out plates and made a sign that said You Are Safe To Be Here. The flag moved in the warm breeze outside the door and children pressed noses to the glass as if cake were a planet they had never visited.

I looked around the room at the faces of people who had been inconveniently human in all the right ways: Dad washing dishes with sleeves rolled to the elbow, the tattoo on his forearm from college days peeking out like a teenager; Mom laughing with Mary’s wife at a joke I couldn’t hear; Aimee bossing the coffee urn with the authority she’d learned in an ICU at three in the morning when no one else would make a decision and she had to. The girls’ basketball team had a dessert table they were running with terrifying efficiency and I promised myself never to underestimate a fourteen-year-old with a cash box.

A woman I didn’t know stood by the door for a long time before she came in. She had a little boy with her who wanted a cookie so badly he was vibrating. She hesitated the way people do when they’re trying to do a thing they are not sure they are allowed to do. I caught her eye and smiled and she came. She bought a cookie and stayed. She told me after an hour that she had left the night before and this morning she wanted to see if she could keep choosing the same good thing again. She asked if we had coffee to go. I said we did, and while I poured I thought of the steps Caleb had written on that card, neat and clear and wrong, and I thought of the steps she was writing in her life now. Step-one, unlock the door. Step-two, put on shoes. Step-three, find a bakery with a flag on its door and the smell of sugar and something like mercy.

There are people who will say this is not a happy ending. They want a prince led away in chains in front of the whole town while a brass band plays. They want confessions shouted from rooftops, a petition circulated, repentance that looks like parade. Real life is quieter. Real life is the clink of a fork against a ceramic plate and the scrape of a chair on wood and the way your own name sounds after you say it to yourself in a room where no one is listening. Real life is not forgetting what someone did and also not setting up camp in that place. Real life is flags that mean we are open and ovens that mean we will try again.

I still sometimes wake and hear the sound like a bird hitting glass. The brain keeps what it keeps. But then the soft morning comes—the dishwasher hum, the smell of coffee, the sound of my father whistling off-key on purpose to make me mad. I stand at the counter and put my palms on wood worn smooth by a thousand small ordinary labors. I close my eyes and remember the rolling pin and the floor and the way a man looked at me like I had cost him and his anger could set the books right. Then I open them and see the shop I built with my people and the girl by the window practicing flute fingerings on a straw and the man in the corner reading his paper like there is nothing wrong in the world because right now, in this corner, there isn’t.

At noon, a shaft of light comes through the front window and lays itself across the counter like a blessing with nowhere else to go. I slice a pie and set the first piece on a plate and slide it across to the woman with the coffee to go. She takes her bite and closes her eyes to do the math of it—sour and sweet, tart and soft—and when she opens them again, she looks lighter by a feather’s weight.

“Thank you,” she says.

“For what?” I ask, and I mean it.

“For the sign,” she says, jerking her chin toward the door. “For saying it out loud.”

You are safe to be here. I had written the words on butcher paper with a thick black marker, not because I believed I could conjure safety with my hand, but because sometimes a bakery is a church without pews and a sign is a liturgy you repeat until your body believes.

After we close, I carry the flag back inside and wipe the pole down. The sky is still summer. The courthouse dome glows like a coin at the end of the street. I lock the door and check it twice and stand with my back to the glass as the train sounds the long note it uses for the crossing. You are safe to be here, I think, and the here expands to hold the town, the ridge, the river, the wide country where women have always told the truth to each other in kitchens and then learned to tell it louder.

I put on the kettle in the back and take down the family cookbook and slide a printout into the sleeve with the lemon bar recipe: a note from Mary with the new trust language, the words that mean two signatures and time, a recipe for keeping a life from being taken. Under that, another printout with a number in big font—one of those lines you call when you’re done calling yourself names for not leaving faster. Above, a yellow sticky note in my own messy hand: Step-one, breathe. Step-two, tell the truth. Step-three, open the door.

And then, because life is not just work and repair, I take a knife and cut myself a second slice of pie and eat it standing up, the way a teenager does, cold from the fridge, because sweetness is a skill too, and I am practicing.

In the fall, my grandmother turned ninety-two. She wore a dress the color of marigolds and earrings that had belonged to her mother. We held the party in the church fellowship hall, because no room holds the sound of old women laughing like that one. After cake, Nana stood with her cane and tapped it once for attention.

“I am shopping for no more husbands,” she said, to laughter, “but I am already married to this life and to you people in particular.” She pointed the cane around the room. “I am not wise, but I am stubborn. Stubborn is about as close as we get to wise around here.” She looked at me, and her eyes were as fierce as the day she’d stood in my apartment while the winter sky laid its cold hand on our heads and said we were leaving. “Stubborn has its uses when a person is learning to be safe.”

We applauded and cried a little, because old women telling the truth will break you open in the best ways. I took home leftovers and stacked them in the fridge and stood at the sink with my hands in soapy water while the flag outside slapped against the pole in a sudden gust. The kettle clicked off. The night train passed, and I said out loud to an empty kitchen, “I am safe to be here.” Then I laughed at myself and said, “I am ridiculous,” because both were true.

Caleb’s mother moved to a different town. The bakery he kept alive by telling stories about love went to auction and a couple from Buffalo bought it for the stainless steel and opened a soup place. People liked the soups. They said the broth tasted like someone had stood in the kitchen a long time, which is what love tastes like after all. Reporters occasionally wrote think pieces about the case—how a small town learned to change its mind. The Maple Ridge Daily editor sent me an email apology with more adjectives than necessary but a sincerity that showed up like a person in jeans to help you move a sofa.

If I tell you that most days now are ordinary, I mean to honor them. The spectacular days are easy to narrate. The ordinary ones are where courage sits quietly and drinks its coffee black and goes to work. I set dough to rise. I fill out paperwork. I call my mother for no reason. I take Nana to the doctor and then to the diner where we always get grilled cheese and tomato soup, and she salts the soup as if it personally offended her, and the server calls her Miss June and winks.

A woman shows up with a resume and a worried mouth and says she bakes but has no references because leaving meant leaving. I hire her on the spot and tell her I don’t need references so much as evidence of stubbornness. She laughs for the first time that day and asks what time to come in on Monday. “Five,” I say. “We do the best work when the town is sleeping.”

On a Sunday afternoon, I stand on the courthouse steps after a 5K for the June Fund and watch the flag lift, bright as a hard candy. A kid I’ve never seen before holds a cup of water out to me and says, “You’re the pie lady,” and for a heartbeat I want to tell him a different Bible I know by heart—one where the arc bends mostly because we bend it, one where men who call control love do not get the last gorgeous word. Instead I take the water and say, “That’s me.”

Sometimes I see a rolling pin in an antique store and my stomach will do its trick and fold. I stand there and breathe until my palms stop sweating. Then I pick up the pin, feel its weight, and put it down. I have a good heavy one at the shop now. Dad bought it. We chose it together. He always calls it a tool, not a weapon, a thing to be used in the mercy of ordinary work.

The day the first leaf falls on the bakery steps, I sweep it into the dustpan and think of the girl I was the first morning after the hospital—the one who thought her life had burned from roof to basement and left only ash. The girl who thought ash is the end. Ash grows gardens if you know what to do with it. You work it into the soil with your hands. You plant something there you can feed your people with. You pat the ground around it and say a small, workmanlike blessing.

I am not brave in the way movies think brave looks. I am steady in the way women in kitchens are when the train’s late and the soup boils over and the child cries because the math is hard. I show up. I put dough in a bowl and cover it with a towel I bought at a yard sale from a woman who had embroidered strawberries at the border so neat I want to cry when I fold it. I unlock the door when the bell rings. I write signs in thick black marker. I take the flag in at dusk and put it out at dawn. I answer the phone “Hearth & Honey, this is Evelyn,” as if nothing in the world could make that untrue.

People will tell you you’re supposed to let go. I am not letting go. I am carrying forward. There is a difference. Letting go suggests the thing wanted to leave and you were the fool holding it back. Carrying forward is what farmers do with seed and what grandmothers do with recipes and what women do with the parts of their lives that did not kill them. You carry the weight until your muscles learn it, and then you are stronger than your past and not because the past got lighter.

When I lock the door at night, the square is quiet except for the flag moving like breath and the long sigh of trucks on the highway. I stand the broom in the corner and turn the sign to CLOSED and tuck tomorrow’s prep list under a magnet shaped like a slice of pie that a child brought me for my birthday from the fair. The ovens are still, but the room is not empty. It is full of what we made and what we’re going to make, of flour in the air and light on wood and the sound my father makes when he laughs from the back room, low and surprised, the sound of a man who knows the ending isn’t a single day in court but a thousand mornings when his daughter unlocks a door and walks into a life she chose.

I flip the deadbolt and step out into the summer night and pull the door until it catches. Then I reach up—because habit is its own liturgy—and touch my fingers to the flag, and let it be a small promise to myself and to whoever needs it: we are open, we will keep opening, and if you are tired and hungry and need to breathe, there is a place at the counter for you.

News

While the entire ballroom was applauding, I saw my mother-in-law quietly drop a “white pill” into my champagne flute — she thought I’d drink it; I swapped the glasses and smiled; she raised hers, the music jolted to a stop, every eye snapped our way — and that was the moment the wedding turned into an unmasking no one saw coming.

At My Wedding Reception, My Mother‑in‑Law Slipped Something in My Champagne—So I Switched Glasses I saw her hand hover over…

“My Dad Works at the Pentagon,” a 10-Year-Old Said. The Class Laughed, the Teacher Smirked—Ten Minutes Later, the Door Opened and the Room Went Silent.

When the bell for morning announcements chimed through the beige halls of Jefferson Elementary, Malik Johnson straightened in his seat…

My dad dragged me across the driveway by my hair for blocking my sister’s car…

My dad dragged me across the driveway by my hair for blocking my sister’s car. The gravel scraped beneath my…

END OF IT ALL – I was told over and over again that I was not welcome at any family events. My mother yelled that events were for real family only.. So when I got married I didn’t invite them and they went crazy asking to fix things but I called such a call

I was taught early that belonging had rules nobody bothered to write down. You learned them by touch: a hand…

On My 29th Birthday My Parents Ignored Me And Sent My Sister To Hawaii — “She’s The One Who Makes Us Proud.”

The morning I turned twenty-nine, my apartment sounded like a paused song. No kettle hiss, no buzzing phone, no chorus…

My wealthy grandmother said, “So, how have you spent the three million dollars?” — I froze right there at graduation — and my parents’ answer silenced the entire family…

The graduation ceremony stretched across the manicured lawn like a postcard of American triumph—burgundy and gold banners, folding chairs squared…

End of content

No more pages to load